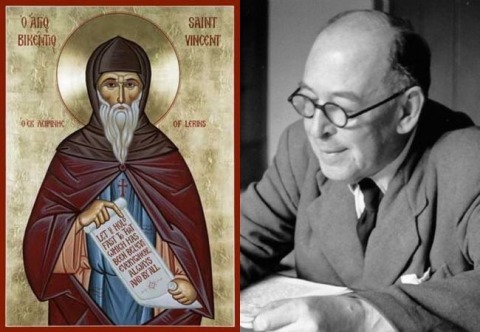

The noble intention of C.S. Lewis’s famous book Mere Christianity was to defend not this sect or that sect, but rather those teachings which had been held by almost all Christians in almost all times and places.

Though Lewis himself proceeded differently, the idea itself goes back to a criterion of orthodoxy proposed by St. Vincent of Lerins in his famous Commonitory. Here are St. Vincent’s own words:

“I have often then inquired earnestly and attentively of very many men eminent for sanctity and learning, how and by what sure and so to speak universal rule I may be able to distinguish the truth of Catholic faith from the falsehood of heretical pravity; and I have always, and in almost every instance, received an answer to this effect: That whether I or anyone else should wish to detect the frauds and avoid the snares of heretics as they rise, and to continue sound and complete in the Catholic faith, we must, the Lord helping, fortify our own belief in two ways; first, by the authority of the Divine Law, and then, by the Tradition of the Catholic Church.

“But here someone perhaps will ask, “Since the canon of Scripture is complete, and sufficient of itself for everything, and more than sufficient, what need is there to join with it the authority of the Church's interpretation?” For this reason — because, owing to the depth of Holy Scripture, all do not accept it in one and the same sense, but one understands its words in one way, another in another; so that it seems to be capable of as many interpretations as there are interpreters. For Novatian expounds it one way, Sabellius another, Donatus another, Arius, Eunomius, Macedonius, another, Photinus, Apollinaris, Priscillian, another, Iovinian, Pelagius, Celestius, another, lastly, Nestorius another. Therefore, it is very necessary, on account of so great intricacies of such various error, that the rule for the right understanding of the prophets and apostles should be framed in accordance with the standard of Ecclesiastical and Catholic interpretation.

“Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all. For that is truly and in the strictest sense Catholic, which, as the name itself and the reason of the thing declare, comprehends all universally. This rule we shall observe if we follow universality, antiquity, consent. We shall follow universality if we confess that one faith to be true, which the whole Church throughout the world confesses; antiquity, if we in no wise depart from those interpretations which it is manifest were notoriously held by our holy ancestors and fathers; consent, in like manner, if in antiquity itself we adhere to the consentient definitions and determinations of all, or at the least of almost all priests and doctors.”

However, attempts to define a “mere” Christianity by building on that phrase “everywhere, always, by all” may go in either of two directions

One is the way intended by St. Vincent, which keeps the phrase in its ecclesiastical context. For when St. Vincent wrote “all,” he was referring to the priests and doctors of the Catholic faith, and when he wrote “always,” he was referring to the consensus of antiquity. Taken in this sense, plenty has been believed everywhere, always, and by all. Taking the criterion in this way, mere Christianity would appear to be Catholic Christianity.

The other way, Lewis’s, is ecclesiastically relativist – which is a little surprising, because in other ways Lewis was light-years from relativism. But when Lewis wrote “all,” he meant all or almost all of those who have called themselves Christians, and when he wrote “always,” he meant all times whatsoever.

I don’t think Lewis realized that in his sense, nothing really has been believed everywhere, always, and by all. Taking the criterion in this way, mere Christianity would appear to be no Christianity.

If Lewis’s book is a great book – and it is -- the reason is that Lewis was better than his method. Had he really followed it, he would have had nothing to say. But he didn’t; and so he did.