The Underground Thomist

Blog

My Woke ProfessorMonday, 10-23-2023

Query:Ever since one of my professors found out I didn’t share his woke opinions, I’ve been having a hard time sharing my interests with them. Suffice it to say, those who preach tolerance can be quite intolerant! Anyway, I would like to have a research plan for studying culture that they can’t dismiss as “racist” (because I believe in being colorblind instead of practicing reverse discrimination), “homophobic” (because I don’t believe all forms of sexual behavior are equivalent), “xenophobic” (because I don’t believe every way of life is equally good), or offensive in some other way, just because I don’t march to their drum.

Reply:I get this question often. What can you do? First, don’t expect to be able to share your interests with each of your professors. Be discrete. Learn with whom you can talk freely, with whom you can’t, who will respect your confidences, and who will gossip. This applies to conversations with fellow students, too. Second, choose your mentors carefully. This is important not only for those already in a graduate program, like you, but also for those who are just choosing one; they shouldn’t go just by ranking or reputation, but should research the faculty in the program first. Having to defend yourself is normal and good for you, and it isn’t necessary that all of your professors be sympathetic to your point of view. However, you need to find at least one or two of the faculty who will be sufficiently likeminded to help you with your projects instead of tearing you down. Naturally, you should expect to be criticized for laziness or sloppy reasoning! But you shouldn’t have to do daily battle just because you don’t hold woke views. Third, although you should try to get along with everyone, you should reconcile yourself to the fact that with some people this is impossible. Avoid them. When you have to deal with them, find things to talk about that interest them, not you, and do your work so impeccably that they find it difficult to criticize. But of course this is good advice even if you aren’t dealing with hostile critics! Fourth, remember that although you must never be complicit with what is unconscionable, there are all sorts of interesting questions about race, family, and culture which don’t even raise issues about reverse discrimination, sexual disorder, or the evaluation of different ways of life. If – as I suspect – you don’t want to study one of the safe questions, but one which is inescapably risky, more power to you! As G.K. Chesterton said, only living things can go against the stream. But find ways to frame your question which intrigue even those whose views are radically different than yours. To do this, you will have to understand them as well as you possibly can. Fifth, plan for the future. One of the most brilliant graduate students I’ve taught framed his research question in the way I’ve just urged, and did his work so well that he disarmed his critics, whose reasons for being interested in his project were quite different than his own. He used his doctoral research to lay the groundwork ahead of time for his next project after getting his PhD. It was much more controversial – but by that time, he had strengthened his position. Finally, have fun. You’re still a young man. Young men like to fight. Learn which things are worth fighting for, and fight prudently: Not with your fists, but with your mind.

|

No Such Thing as Virtue?Monday, 10-16-2023

The Good Samaritan is a model of virtue because he gave assistance to a stranger who sorely needed it, at significant cost to himself, after several who might have been thought to have a greater duty to help passed the sufferer by. But what if there is no such thing as virtue? What if the Samaritan wasn’t really good? What if the he merely happened to relieve suffering that time, but another time might have turned a blind eye to it? What if it all depends on the occasion? Maybe even Caligula acted kindly at times. Maybe even Mother Theresa sometimes didn’t. That’s what I hear occasionally from students who are learning of the classical doctrine of the virtues for the first time. They tell me that there is no such thing as stable moral character. Virtue is non-existent, like ghosts and unicorns. How do they know? Because that’s what some of their psychology professors tell them. After a certain number of students told me this, I did a little digging. Yes, some psychologists really do propound such a theory, and it’s a convenient excuse if one is considering kicking the dog, cheating on the test, or flipping off the driver in the next lane. But there is much less to it than meets the eye. The experiments on which these psychologists base their hypothesis are actually somewhat interesting, but what they show is another question. In the first and most famous such experiment, by John M. Darley and C. Daniel Batson, seminary students were recruited under the pretext of having them give talks on assigned topics – some on seminary employment, others on the Good Samaritan. The researchers had the students fill out personality questionnaires covering their views and attitudes toward religion. At a certain point, under another pretext, the students were asked to walk to a different building. Some were told to hurry; some weren’t. On the way, each student passed a confederate of the experimenters who was slumped in an alleyway, moaned, and gave a few coughs. The question was: Would the passerby stop to give assistance to the supposed sufferer? Of the seminarians who were not in a hurry, most stopped. Some, in fact, were so eager to help that the person who was feigning distress had a difficult time getting them to leave before another experimental subject came along. On the other hand, of the seminarians who were in a hurry, most did not stop, and there was very little correlation between whether they stopped and what they had said in their questionnaires. From this finding, many psychologists have concluded that morally irrelevant situational factors like being in a hurry matter far more than supposed virtue in determining how people will behave. Ergo, stable moral character is a myth. When I returned to the original experiment, I was surprised to find that Darley and Batson did not actually draw such a silly conclusion. Their discussion of what their experiment meant was much more thoughtful, and rightly so, for everyday life constantly reminds us of the importance of differences in character. One man is a good husband, another is a louse. I can loan my car to my daughter-in-law, but I had better not loan money to my brother-in-law. The hypothesis that there is no such thing as stable moral character is also contradicted by the experience of banks, insurance companies, and law enforcement. That’s why we have credit records, actuarial scores, and rap sheets. We therefore have excellent prima facie reason to that there really is such a thing as stable moral character, and that it is very important. So what is wrong with the no-such-thing-as-virtue school of thinking? Why shouldn’t such experiments be taken as showing that stable character is nonexistent? The two original experimenters themselves give the first reason for thinking so. Post-experiment interviews suggested to them that some of the seminary students may have been torn between stopping to help the fellow in the alley, and continuing on their way to keep their promise to help the experimenter. “And this is often true of people in a hurry,” they write. “Conflict, rather than callousness, can explain their failure to stop.” But the literature on such experiments not only tends to ignore this point, but cexhibits other blind spots too. The first thing it overlooks is that although being in a hurry made a difference, it didn’t make all the difference. A good many seminarians in a hurry helped; a good many not in a hurry didn’t. From a failure to find a complete explanation of the difference in behavior, it doesn’t follow that the complete explanation lies in circumstances rather than moral character. The second thing it overlooks is that it’s very hard to measure virtue independently of what people actually do. For example, being in seminary is hardly evidential; on one occasion a student asked me for a recommendation to seminary so that he could become a minister just because his dad, a Unitarian pastor, made a pretty good income. (The student’s other top career choice was restoring vintage cars.) Responses to the sorts of personality questionnaires that psychologists ordinarily use aren’t much help either. In the original Darley and Batson study, the highest correlation was between the behavior of the seminarians and whether they viewed religion as a “quest” – but what does that mean? Third, virtue comes in degrees. Most of us are pretty flawed, and are sorely challenged by our temptations. We win some, we lose some. Each time someone wins a match, it is a little easier to prevail in the next one. Each time he loses, it’s a little harder. So the fact that passersby often fail to help someone they really ought to help doesn’t mean that there is no such thing as virtue, but, at most, that not many of them have it to the very highest degree. Fourth, “virtue vs. circumstances” is a false alternative, because even highly virtuous people don’t always act the same way – and they shouldn’t. A perfectly virtuous person will always act virtuously, but the virtuous course of action is not always the same. For example, the virtue of generosity does not always require giving everyone who asks for something what he wants. It depends on circumstances. Granted, the proponents of the “no such thing as virtue” theory do take a stab at it at the fourth problem. As we saw, they argue that the differences in behavior which experimental subjects exhibit depend not just on circumstances, but on morally irrelevant circumstances, such as whether they are in a hurry. To say this we have to overlook their admission that this particular circumstance may not have been morally irrelevant after all. But even aside from that problem, let’s not be in a hurry to draw conclusions. Consider that fellow in the alleyway. Were the passing seminarians convinced that his distress was genuine, or did they wonder whether he was faking? After all, some people do feign distress, whether for predatory or non-predatory reasons. Besides, the fellow was faking, and it is unreasonable to assume that passersby wouldn’t sense something “off.” It isn’t clear whether the post-experiment interviews investigated this possibility. What kind of distress did the passersby think the fellow in the alleyway was in? If he had fallen and banged his head, then he could probably be helped. If he was drunk or desperate for a fix, then they probably didn’t have means to help him. If he was agitated because he was high on PCP, it would be dangerous to try. In many cities these days, authorities don’t even respond to 911 calls about people acting distressed. Sometimes not responding is policy; sometimes they are just overworked. Even people who want to be helpful can’t help everyone. It would be impossible. We have to make choices. Did the passersby even notice the fellow? Several of the seminarians obviously did – they stepped over him! Most of them mentioned to the researchers that they wondered whether he may have needed help. In many cases, though, it seems that this thought occurred to them only afterward, not at the time. Being oblivious when hurrying is surely a flaw, but it is a different flaw than noticing and not giving a damn. Not to let the passersby too easily off the hook, suppose we accept the judgments of no-such-thing-as-virtue thinkers concerning whether they did the moral thing. This merely exposes a fifth problem: Where are such thinkers getting these judgments? This question is important because according to the classical view, every other virtue hinges on the virtue of practical wisdom, which involves judging well. For example, I may have a perfect readiness to be generous – and such a disposition is nothing to take lightly – yet I may be a poor judge of who stands in need of my generosity. Now plainly, the psychologists who say there is no such thing as virtue are confident in the stability of their own moral wisdom. Otherwise, how could they presume to offer any judgments whatsoever about what is morally relevant or irrelevant? But if their entire methodology is predicated upon their having the stable virtue of moral wisdom, then how can they conclude that there is no such thing as stable moral character?

Reference:John M. Darley and C. Daniel Batson, “From Jerusalem to Jericho: A study of Situational and Dispositional Variables in Helping Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 27:1 (1973), pp. 100-108. Related:Commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Virtue Ethics

|

InsularityMonday, 10-09-2023

What scholars think about the world at large tends to come not from the world at large, but from other scholars. Without much experience of ordinary people, many of them take for granted that ordinary folk are bigots, especially in certain parts of the country. It amazes me how hard it is to crack the shell that protects such opinions from reality. At a faculty Christmas party a few years ago, a colleague was intrigued to learn that my wife and I spend part of every summer in a poor section of the Appalachians. Why on earth retreat to a place like that? He was a nice guy – most of my colleagues are nice people -- and he understood the pleasure of visiting family and old friends. He also liked vacations. But he definitely didn’t understand the refreshment of getting out of the incestuous university culture into a different kind of world with different kinds of people. So tell me how it’s different, he asked, and I obliged. One of the points I emphasized was how important extended family is in eastern Kentucky, by contrast with a high-tech, high-mobility burg like Austin. Having grown up, unlike my wife, in an ultra-nuclear family, I’m fascinated by close family ties. Everyone up in the hollers knows his relatives out to double second cousins once removed. When introductions are made, the first thing people want to know is “Who are your people?” Instantly my colleague told me, yes, he had been disturbed to see a small racist demonstration at a highway intersection when he was driving through a southeastern town. What? Puzzled by what seemed a change of subject, I explained that white supremacist organizations are pretty much unknown where we go in the summer. I understood that he viewed them as central to southern culture. What puzzled me was why he seemed to think that I did too. Finally I realized that when I had used the term “clan,” meaning extended family, he had assumed that I was talking about the KKK. Never mind the context. After all, man, the south! What else could I have been talking about? (Besides, wouldn’t I have had all the same opinions he did?) Easy mistake, easily correctible. Or so I thought. Quickly I explained that I hadn’t meant “Klan,” with a big K, but “clan,” with a little “c.” Relatives, you know. Your family. Your kin. But it was as though he couldn’t hear me. Extended family didn’t have a slot in his fixed view of the southeastern United States. White supremacy did. According to a certain common view, higher education makes people more broad-minded and open to new information. But in their own way, universities can be narrower than any village. I would say that to live in that world is a lot like living up a holler, but a holler has a lot more variety.

|

The Real Problem with the SuperrichSunday, 10-01-2023

Other than from sheer jealousy, why should anyone object to some people having far more wealth than others? The spiritual argument is that the superrich are vulnerable to the grave danger of relying on wealth rather than God for their security and beatitude. “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God,” says Christ. However, although the passage provides an excellent reason for warning the ultra-wealthy, it doesn’t provide a reason for objecting to them. Coercion should be used only to enforce the common good, not the private good. The economic argument is that by having all that wealth, the ultra-wealthy are taking wealth away from the rest of us. “The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer.” No, a competitive economy is not a zero-sum game. Wealth employed in productive enterprises increases the wealth of those less favored, for instance by generating jobs. The social argument is that disparities of wealth produce such envy that the society is torn apart. In itself, however, this isn’t so much an argument against disparities of wealth as an argument against flaunting them. The ethical argument is that justice requires equality. Not so fast. Justice requires treating people who are equal in relevant respects equally; for example, we shouldn’t treat equally qualified job applicants differently because of race. But justice doesn’t require that everyone have the same stuff. The political argument is that wealth is a means to political power, and those who crave wealth tend to be the sorts of persons who crave power too. You can run an oligarchy if some people are superrich – and some oligarchies are better than others -- but if you try to run a republic that way, you will lose it. The first four arguments are weak, but I can’t think of a convincing retort to the political argument. Not only is it the strongest, but it alters the force of the others. As to the spiritual argument: If superwealth produces dangerous concentrations of power, then the superrich are vulnerable not only to temptations to hurt themselves, but also to temptations to hurt others. The goods at risk are no longer merely private. As to the economic argument: If superwealth makes some unusually powerful, then they will almost certainly use their power to give themselves non-competitive advantages, such as government subsidies. A competitive market tends to increase everyone’s wealth, but a rigged market may make many poorer. As to the social argument: Although it may be possible to conceal extreme disparities of wealth, it is hard to blame have-nots for resenting them if the harm they suffer from them is real, rather than imaginary and churlish. As to the ethical argument: Justice doesn’t require that everyone have the same stuff, but it does require a reasonably close approximation of a level playing floor. If extreme wealth can radically tip the floor, we have a problem. Granted the dangers of great concentrations of wealth in private hands, what can be done about it? The problem is that most of the conceivable cures are even worse than the disease. Progressives propose taxing all that wealth away (except, of course, from their allies), and instituting a “managed” economy. Many of the superrich even support progressive schemes: Wall Street is mostly Democrat these days. It isn’t difficult to see why, for if the progressive program were carried out thoroughly, it would not destroy concentrations of power, but only replace private concentrations of power with the concentration of power in the government. Those who expect to gain from government patronage welcome the prospect. The present oligarchy, despite its flaws, tends to generate some checks on governmental power. The new kind of oligarchy would be a runaway car with nothing at all standing between the government at the top of the hill and the citizen at the bottom. What about conservatives? Some simply deny the disease. This is obviously unsatisfactory. Others seem resigned to living with it. Since it is a progressive disorder – no pun intended – this is not realistic either. Following the present trajectory, the political order will not stand still, but will advance further into oligarchy. Years ago as a young scholar, when I first began studying political theory, I was impatient with Aristotle, who, after saying that oligarchy was one of the “perverted” forms of government, asked not how to avoid it, but how to ameliorate it. I am not so impatient with him now. Political theory does not concern itself with the impossible. On the other hand, perhaps the pragmatic suggestion of a mixed and balanced form of polity has not yet run its course. If concentrations of power cannot be avoided, maybe the best thing is to encourage countervailing concentrations, so that each kind of power is in competition with each of the others. Although this is far from a new idea, it is much more difficult to put into practice than one might think. For instance, not so long ago, many people viewed labor and capital as countervailing forces which would keep each other from doing mischief. Since then, we have seen that big corporations and big industrial unions can work together to obtain governmental patronage and undermine competition. Much the same sort of thing happens inside government itself. The Founders expected the branches of government use their powers to curb each other, but if two branches, or two chambers of the legislature, can both become more powerful by acting in concert, they will do so. So much for checks and balances. Do you think it’s hard enough to build a house of sticks? Try to build it when the sticks are alive, squirming, growing, and jostling for position. I don’t say it’s impossible, but the work is never done.

|

Paradoxical BeautyMonday, 09-25-2023

These lines, delivered by Joseph Ratzinger three years before his accession to the papacy, are such pure gold that I can add nothing to them. They come from a talk he gave in August, 2002, titled “The Feeling of Things, the Contemplation of Beauty,” and ought to be better known – not least by those of us who attempt rational apologetics. +++++ + +++++ “All too often arguments fall on deaf ears because in our world too many contradictory arguments compete with one another, so much so that we are spontaneously reminded of the medieval theologians’ description of reason, that it ‘has a wax nose’: In other words, it can be pointed in any direction, if one is clever enough. Everything makes sense, is so convincing, whom should we trust? “The encounter with the beautiful can become the wound of the arrow that strikes the heart and in this way opens our eyes, so that later, from this experience, we take the criteria for judgment and can correctly evaluate the arguments. * * * “Now however, we still have to respond to an objection. We have already rejected the assumption which claims that what has just been said is a flight into the irrational, into mere aestheticism. “Rather, it is the opposite that is true: This is the very way in which reason is freed from dullness and made ready to act. * * * “Today another objection has even greater weight: … Can the beautiful be genuine, or, in the end, is it only an illusion? Isn’t reality perhaps basically evil? The fear that in the end it is not the arrow of the beautiful that leads us to the truth, but that falsehood, all that is ugly and vulgar, may constitute the true “reality” has at all times caused people anguish. “At present this has been expressed in the assertion that after Auschwitz it was no longer possible to write poetry; after Auschwitz it is no longer possible to speak of a God who is good. People wondered: Where was God when the gas chambers were operating? This objection … shows that in any case a purely harmonious concept of beauty is not enough. It cannot stand up to the confrontation with the gravity of the questioning about God, truth and beauty. * * * “[In Christ] the experience of the beautiful has received new depth and new realism. The One who is the Beauty itself let himself be slapped in the face, spat upon, crowned with thorns; the Shroud of Turin can help us imagine this in a realistic way. However, in his Face that is so disfigured, there appears the genuine, extreme beauty: The beauty of love that goes ‘to the very end’; for this reason it is revealed as greater than falsehood and violence. Whoever has perceived this beauty knows that truth, and not falsehood, is the real aspiration of the world. It is not the false that is ‘true,’ but indeed, the Truth. “It is, as it were, a new trick of what is false to present itself as ‘truth’ and to say to us: Over and above me there is basically nothing, stop seeking or even loving the truth; in doing so you are on the wrong track. The icon of the crucified Christ sets us free from this deception that is so widespread today. However it imposes a condition: That we let ourselves be wounded by him, and that we believe in the Love who can risk setting aside his external beauty to proclaim, in this way, the truth of the beautiful. * * * “Is there anyone who does not know Dostoyevsky’s often-quoted sentence: ‘The Beautiful will save us’? However, people usually forget that Dostoyevsky is referring here to the redeeming Beauty of Christ. We must learn to see him. If we know him, not only in words, but if we are struck by the arrow of his paradoxical beauty, then we will truly know him, and know him not only because we have heard others speak about him. Then we will have found the beauty of Truth, of the Truth that redeems. Nothing can bring us into close contact with the beauty of Christ himself other than the world of beauty created by faith and light that shines out from the faces of the saints, through whom his own light becomes visible.”

|

The Old Is-Ought ThingMonday, 09-18-2023

Query:I’m writing to you about the old is-ought thing. Years ago, in the Q&A period after a lecture I heard you give at a university I was then attending, you replied to someone who said that we can’t get an “ought” from an “is” – you argued that on the contrary, descriptive premises do have evaluative conclusions: A “good” eye sees, and a “bad” eye doesn’t. Since good is to be done, one should fix the bad eye. But it seems to me that the goodness of a good eye is not moral goodness like the goodness of a good man. We mean only that it does what we want it to do. I don’t actually deny a connection between what “is” and what “ought” to be done. I just don’t think you can connect them without bringing in premises about God’s will.

Reply:It’s true that the adjective “good” means something different for eyes than for people. But are you so sure these two senses of “good” have no relation? In a seminal article in 1952, the philosopher Peter T. Geach pointed out that there is a difference between predicative and attributive adjectives. The adjective “red” is predicative; it means the same thing no matter what kind of thing we are talking about. By contrast, the adjective “fast” is attributive; what it means depends on what kind of thing we are talking about. The evaluative adjective “good,” like the adjective “fast,” is attributive, because its meaning depends on the kind of thing we are talking about – just as we mean something different when we call a rocket “fast” than when we call a little boy who is running “fast,” so we mean something different when we call a sandwich “good” than when we call a medicine “good.” However, the applicability of the word “good” doesn’t depend merely on what we want something to do – it depends on the function or proper work of the thing. Since even if I don’t care about seeing, the proper work of an eye is to see, a good eye is one that sees well. Since even if I don’t like sports, the proper work of a soccer ball is to be suitable for playing soccer, a good soccer ball is one that has the qualities requisite for the game. To apply this teleological analysis to the goodness of a human being, we must know what a human being’s proper work may be. Can we get anywhere with this question? I think so. As Aristotle rightly tells us, the proper work of a human being is living well and doing well; it means the appropriate exercise of his powers. This means pre-eminently his highest, rational powers, which in turn regulate his lower ones. In the practical realm, the argument leads us to the conclusion that a human being must live in accordance with the virtues. But as Thomas Aquinas points out, in the still higher, contemplative realm, it leads to the conclusion that a human being must come to see God, not just through words and images, but as He is in Himself. Now we aren’t naturally endowed with the power to see God as He is in Himself. On the other hand, we are naturally endowed with the potentiality to receive from Him the grace which makes this possible. Therein is the overflowing joy of the blessed. As you see, I agree that God belongs in the picture – but perhaps we mean different things by this. For I don’t think I need to say “God commands P” or “God forbids Q” just to talk with someone about whether something is good or whether we are living well. But of course, if the conversation about living well lasts long enough, eventually it will be difficult not to talk about Him, since He is the author of what it is to live well, and none of the finite goods of this world are enough. Subsequent give and take: “Is the intellectual vision of God in His essence the same as glorifying God and enjoying Him forever?” I would say it is a good description of what we are doing when we are glorifying Him and enjoying Him forever. “As a telos, though, isn’t the vision of God pretty vague?” In this life, certainly our mental images of God are vague, since we don’t perceive Him directly with our minds. But God in His own being is not vague. St. Paul says that now we see in a mirror darkly, but then, we will see face to face, knowing as we are known. That doesn’t sound vague to me. And even now, when we do not yet see God Himself, we can say a lot about Him without a bit of vagueness. For example, He exists; He is the origin of all good; there is only one of Him; He is not composed of other things; and He is the Creator of all that is. “Isn’t there a difference between judging character, judging conduct, and judging a whole life?” Of course. “But isn’t it the case that Aristotle provides materials only for judging a life as a whole?” To me that doesn’t seem to be at all what he says. True, he says we can’t tell whether a man has been happy until his life has been completed. But we can certainly say that this or that act conduce or detract from his flourishing. “So would you call yourself a virtue ethicist?” If the question is whether I think any reasonable account of the moral life has to deal with the virtues, then yes. But if by “virtue ethics” you mean an approach that tries to get along without ever mentioning any rules -- this really is how some people use the term – then I think it is absurd. “But doesn’t MacIntyre teach that virtues are always relative to practices?” In his later work, Alasdair MacIntyre explicitly contradicts this view. For example, he does think the virtue of honesty is “internal” to the practice of speech – but he also regards speech, undertaken with a view toward reaching agreement in the truth, as a universal human practice, universally necessary for human flourishing. It isn’t something we can take or leave, like the practice of baking corn muffins. “But aren’t the virtues always relative to roles? For example, couldn’t ruthlessness be a virtue for a soldier?” Someone who willingly does what is intrinsically evil so that good will result may be a “good” assassin, but he is neither a good man nor a good soldier. Of course he will seem a good soldier if you view good soldiering as mere efficiency at killing, but not if you view war the way Augustine viewed it. The purpose of a just war, he observed, is to bring about rightly ordered peace. Thus the principles of just war are not criteria for when you may commit atrocities, but criteria for avoiding them – and a good soldier will observe them. “When we get right down to it, isn’t the nature of the virtues vague?” I don’t think so. For example, it’s pretty clear that fortitude is a virtue, that it requires choosing the right action in perilous situations, that that the disposition to do it is acquired by repeatedly doing it, that it is opposed by cowardice on one hand and rashness on the other, and that we need wisdom to discern the difference. True, fortitude doesn’t always require the same choice. Sometimes the right thing is to advance toward the danger; sometimes to retreat from it. But that doesn’t make fortitude “vague” any more than trying to stay alive while crossing the street is “vague” just because it’s not always safe to cross. “If you think they are precise, then do you deny the need for judgment?” You are confusing questions like whether we can say precisely what a virtue is, and whether there is a right answer to the question “May I do this?”, with the question of whether I can reach that right answer without exercising judgment. Of course I need judgment, because I can’t program a computer to tell me who has courage, or whether in a given situation courage requires holding my position or advancing. Even so, those who do have courage usually agree pretty closely about which deeds are cowardly and which ones are rash. “But don’t you agree that at least the way people talk about the virtues is vague these days, for example in the public school system?” Oh, yes, and sometimes worse than vague. People say a lot of vague things about quantum mechanics too. So what? It isn’t vague in itself, and the math seems to be pretty well understood by those whose business is to understand it. Quantum physicists speak in terms of probabilities, but “P will happen with probability Q” is very different from saying “Who knows whether P will happen?” Similarly, “The courageous choice avoids both rashness and cowardice” is very different from saying “Who knows what courage is?” “But surely you don’t think that we can make a list of virtues that everyone should have, do you?” Sure I do. What’s wrong with the classical list, justice, fortitude, temperance, wisdom, faith, hope, and charity? To make the list complete, of course, we should include not only each of the four cardinal and three spiritual virtues, but also the “parts” or subordinate virtues of each one. The virtue of patience, for instance, is a subordinate virtue of fortitude; the virtue of honoring parents, of the virtue of justice; and the virtue of modesty, or the virtue of temperance. “But even if you think we can list them, you don’t imagine that we can describe them without crippling ambiguity, do you?” I’m afraid I do. Thomas Aquinas did a superior job of this. For starters, look here. I’ve written about his analysis here. “But how could you suggest that goodness lies in superficially good rules and virtues instead of in fellowship with others and walking with God?” What a false alternative! I don’t think goodness lies in rules and virtues instead of in human fellowship and walking with God; I think the rules and virtues are norms for human fellowship and walking with God. I would also deny that virtues like charity and justice, and rules like being faithful to our spouses, are only “superficially” good. True, some marital counselors tell people that a little adultery might be good for their marriages. I would tell such a counselor that he didn’t have a clue about marital love. Perhaps in calling rules like being faithful to our spouses merely “superficially” good you mean something different -- that someone might follow them for bad motives. If I am faithful to my wife not because I love her with the love of charity, but only so that I won’t get caught cheating, then yes, my motive is stained and I cannot please God. But for this-worldly purposes, we should sometimes be grateful even for bad motives. Maybe the only reason Dad sticks with Mom instead of having an affair with his secretary is that he doesn’t want a bad reputation. Then he is not an admirable man, but the children will still be better off. “But the pagans thought they were virtuous too. Doesn’t that cast doubt on what you say?” From the fact that a lot of people and a lot of nations think themselves more virtuous than they are, how does it follow that there isn’t any truth about virtue to be found? What really follows is that the vice of self-righteousness is widespread. A lot of people and a lot of nations have also thought the earth is flat. Does it follow that there is no truth to be found about the shape of the earth? I find enormous insight in St. Augustine’s wonderful analysis of how the glittering glory of the pagans was not true virtue, as they thought it was, but only a vice masquerading as virtue. But I also take seriously his teaching that there really is such a thing as virtue, that it is necessary for the right ordering of our loves, and that we ought to practice it. Don’t let your judgment be paralyzed by the fact that some people judge badly. +++++ +++ +++++ We seem to be pretty far apart, but this will have to close our exchange for now. Thank you for writing. I assure you that I haven’t neglected these things.

|

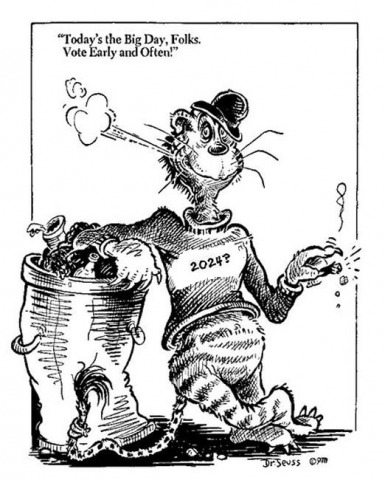

What Do You Mean, The Election Was Crooked (or Wasn’t)?Monday, 09-11-2023

Donald Trump and his defenders argue that the 2020 election was rigged. His critics protest that there is no compelling evidence of fraud. A point mostly missed about this controversy is that the two sides talk past each other. They are using different definitions, assumptions, standards of judgment, and rules of evidence. As to definitions: By a crooked election, the defenders mean only a fraudulent election, but the critics mean one which is rigged. Rigged and fraudulent elections are not the same thing. For an extreme case, consider an election with no coercion and no miscounting, in which everyone is honest, only qualified voters vote, and only one party is allowed to run candidates. The election isn’t fraudulent, but it’s plainly rigged. Its outcome is a foregone conclusion. Now consider an election in which dramatic changes in voting rules make mail-in voting and ballot harvesting much, much easier. That’s what we had in 2020, and what we may have in 2024. Should such an election be considered rigged? The critics think it is rigged because whether fraudulent or not, it invites fraud, as well as manipulation: Fraud, because mail-in voting and ballot harvesting make it much easier for legally unqualified persons to cast votes; manipulation, because the earlier people send in their votes, the less information they have about the candidates. One party or the other may be better positioned to exploit these facts, and doing so may be part of its strategy. The defenders say all this business of inviting fraud is mere speculation. And as to manipulation, who are we to say how quickly voters should make up their minds? But now we come to the differences in assumptions, standards of proof, and rules of evidence. In assumptions, the critics and the defenders are unequally suspicious. The critics think that the stronger the temptation to commit fraud, the more people will engage in it, and the more effort it requires of them to become well informed, the fewer will go to the trouble. But the defenders think we shouldn’t draw such dark conclusions without compelling evidence. They resist criticism of electoral rules on the basis of what might happen, and insist that we consider only what can be proven to have happened. In standards of proof, the critics and the defenders rely unequally on courts. The defenders emphasize that no court has found the case for massive fraud sufficient. “You have had your day in court, and you have lost.” But the critics believe that although courts are right to use the standard “innocent until proven guilty” when individuals are accused of crimes, life would be impossible if we made probable judgments that way. For judging who to marry, whether to cross the street, or how to design electoral procedures, they say, the standard should be common sense grounded in human experience. In rules of evidence, the critics and defenders disagree about what should be counted as a fact or a possible fact. The defenders demand judicially admissible evidence of phony votes. But the critics believe that it is in the very nature of successful cheating not to be easily discovered. They are also willing to weigh many sorts of evidence of phony voting which a historian might be right to take into account, but which a court of law must reject out of hand. Logically, it would be entirely possible for those who deny that the election was fraudulent to be justified by their lights, but for those who say that it was rigged for fraud to be equally justified by theirs. Questions about assumptions, definitions, standards of proof, and rules of evidence are largely about the meaning of fairness and the requirements of prudence. They surely have right answers, but the right answers can’t be ascertained by the crude techniques of the “fact checkers.” Unfortunately, the patient discussion of these difficulties is hindered and skewed by the fact that one side risks public censure or even legal punishment for peacefully pressing its views, and the other side doesn’t.

|