The Underground Thomist

Blog

A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 7 of 10Tuesday, 05-26-2015

I don't like the sound of this. If there really is a natural moral law, then democracy is over with. Why? Because there would be no decisions left for legislators to make. If they did try to make any, judges would just say "The natural law says" and overrule them. That's doubly mistaken. In the first place, there would be plenty of decisions left for legislators to make. Why? Because only the foundational principles of the natural law are known to all -- only the moral basics. The remote implications remain to be worked out and fashioned into rules. But if judges thought the legislators had worked out those remote implications badly, they would invoke natural law to overrule them. Some might try. But I suggest that there is only one situation in which it would be allowable for courts to refuse to recognize a legislative act on grounds of natural law -- if the legislature had violated one of the moral basics, for example by punishing the innocent, or by authorizing some people to murder others. The reason judges could invoke the natural law against legislators in that sort of case is that they know the moral basics every bit as well as legislators do. But here's the rub: Judges are not just as good at working out the remote implications of the natural law. They have no call to refuse to recognize a legislative act in that sort of matter -- much less make law on their own. Why aren't they just as good at working out the remote implications of the natural law? Because of the difference in their jobs. Legislative procedures are adapted to developing general rules; judicial procedures are adapted to applying these general rules to the facts of particular cases. Courts do not anticipate cases not actually before them; legislatures must anticipate cases not actually before them. That is what we have them for. So you're saying that nothing in the natural law forbids the separation of functions. That's right. It's perfectly all right for the framers of a constitution to give one job to legislatures and a different job to courts. I think they should, myself. So it's okay for legislatures to consider the natural law, but not okay for courts to do so. That not how I'd put it. Sorry; I should have said, so it's okay for both courts and legislatures to consider the moral basics -- but only legislatures should consider their remote implications. That's not quite how I'd put it either. How would you put it, then? It's okay for both courts and legislatures to consider the moral basics -- but as to their remote implications, courts should defer to legislatures. Isn't that what I said? No. There is a difference between not considering the remote implications at all, and deferring to the legislature about them. I don't see why. How about an example? Here's how one codification of law explains when contracts are binding and when they aren't – I’ve borrowed it from Charles Rice, who is quoting the Restatement of Contracts, 1932, Section 90: "A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of a definite and substantial character on the part of the promisee and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise." Put more simply -- Never mind, I get it. Put more simply, if breaking the promise would cause injustice, then the contract is binding. Correct. Now suppose that the legislature has enacted that wording into law, and a court has to interpret it. Do you see a problem? No. The legislature hasn't told the court what injustice is. It expects the court to know that already. Oh, yes. But so what? So even though the court defers to the legislature by accepting the general rule which the legislature has given to it, it may be forced to work out some of the remote implications of the natural law, just to figure out what the legislature means. But it still accepts legislative intent as the rule. I see now. Then you see that nothing about the natural law encourages judges to lose their heads. Perhaps not. I would even say that the strongest encouragement to runaway judicial activism is denying the natural law. A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 8 |

Does Calling It Family Make It So?Monday, 05-25-2015

Mondays are reserved for student letters. This student writes from Latin America. Question: In the past year, in Peru, has come forward the debate about gay marriage. It has produced a lot of talking and writing on both sides. My teachers have given their opinions too. They think that the idea of family can change. I think they’re wrong. There is a difference between calling a thing family and a thing being a family. What I’d like to ask is whether you think the family can change. If it can’t change, why do many people seem to think otherwise? But if it can change, then is there any reason to not allow same-sex couple to marry or to adopt children? Reply: Certainly people in different times and places may hold different ideas about the family; even in our own time people hold different ideas about it. But not all of these ideas are equally correspondent with the requirements of our nature. So if the question “Can the idea of the family change?” is taken to mean “Can people hold different opinions about the family?” then the answer is “yes,” but if it is taken to mean “Can the natural laws of family life change?” then the answer is “no.” On the other hand, the natural laws of family life do not require that all families do everything in exactly the same way. There are a thousand possibilities of melody, but the principles of harmony that make melody different from noise are the same for all of them. There are a many kinds of individual personality, but the principles of virtue that make a good person different from a bad one are the same for all of them. And there are many kinds of happy family, but the underlying principles of sound family order are the same for all of them. The thing we overlook is that one of these principles is faithful, heterosexual monogamy. To illustrate, let’s first compare monogamy with polygamy. Unlike monogamy, polygamy undermines what natural law thinkers call the unitive and procreative goods – the very goods that marriage is all about. The unitive good is weakened because if the man does not give himself to his wife exclusively, then neither can he give himself to her totally. It is further weakened because it tends to put women in the position of servants or chattel and breeds jealousy among a man’s various wives. The procreative good is weakened because the relation between the children and their father is attenuated, and because the children of different wives are likely to be in competition for the affection of their father. I might add that polygamy is also socially unjust and undermines solidarity among the classes. If rich men have multiple wives, many poor men will be unable to marry at all. Now let’s compare polygamy with heterosexual promiscuity. Although polygamy undermines the unitive and procreative goods, at least it does not utterly destroy them. Promiscuity does. It destroys the unitive good because the man and woman have no commitment to each other, and it destroys the procreative good because children grow up without fathers -- or with a succession of temporary “fathers” who are not interested in them. To return to your question, so-called gay marriage also destroys the unitive and procreative good. That is why it is not really marriage, whatever the law may call it. The relationship is both intrinsically non-procreative and intrinsically non-complementary. In other words, by nature two persons of the same sex cannot produce children, and by nature they cannot balance each other. It may be objected that two persons of the same sex can adopt, but this distorts the order of the family because the child needs both a mother and a father, and the two are not interchangeable. By the way, when I say that faithful, heterosexual monogamy is a principle of good family life, I don’t mean that every monogamous arrangement of family life works equally well. For example, children need not only their mothers and fathers, but also their grandmothers and grandfathers; the “nuclear” arrangements of the industrialized countries are not ideal. You also ask why people disagree about the principles of family life. There are two reasons. One is innocent mistakes. It may be especially difficult to arrive at a sound understanding of happy family life if one has never experienced it, a circumstance which is unfortunately more and more common. But another reason is self-justification, because unrepented sexual selfishness and other bad motives drive people to make excuses for practices which are really indefensible. Sometimes people even defend bad practices in which they do not participate, just to make sure that their own lives are not criticized either. Tomorrow: A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 7 of 10

|

Better Late Than NeverSunday, 05-24-2015

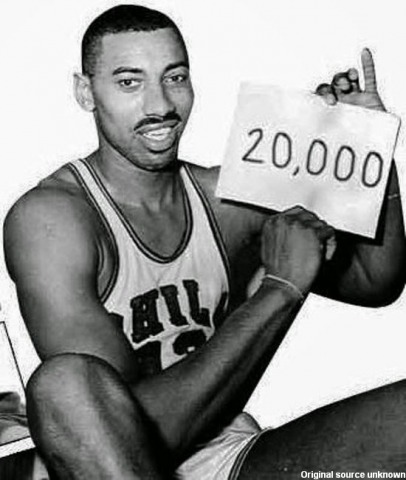

“With all of you men out there who think that having a thousand different ladies is pretty cool, I have learned in my life I've found out that having one woman a thousand different times is much more satisfying.” -- Wilt Chamberlain, 1999 interview with Al Meltzer For the record, it’s unlikely that he really bedded 20,000 women. But I’m glad he learned something before the end. Tomorrow: Does Calling It a Family Make It So?

|

A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 6 of 10Saturday, 05-23-2015

Maybe we make up right and wrong. Maybe human nature doesn't have any inbuilt meaning; maybe the way of life I choose has moral meaning just because I choose it. If you say that, aren't you supposing that one part of human nature does have meaning apart from your choosing -- aren't you ascribing meaning to the will, the choosing power, itself? Why do you say that? Because if it didn't have meaning, then how could it give it? You can't get something from nothing; you can't get meaning from the meaningless. When you say that human nature has no inbuilt meaning so that only your choices matter, what you're really saying us that exactly one part of human nature does have inbuilt meaning: The part that makes your choices. What difference does that make? It's a bit arbitrary, isn't it? If the will has inbuilt meaning, why shouldn't the other parts of human nature have inbuilt meaning too? Why should every part be meaningless except that one? So what if they do have moral meaning? That doesn't stop the will from having moral meaning. Of course not. But it stops it from having the meaning that you want it to. It isn't free to confer meanings on things that have inbuilt meanings already. In that case, maybe nothing has moral meaning. If you really believed that were true, then you wouldn't bother to argue with me. Then maybe we create moral meaning. Even supposing that human beings can create, surely a morality is not the kind of thing we can create. The whole meaning of morality is a norm which obligates us whether we like it or not. If we create it, then we can change it to suit ourselves. But if we can change it to suit ourselves, then it is not morality. But we create other things. Why not this one? I think I've just told you why not! But in fact we cannot genuinely create anything; we are inventive, but our inventiveness is not of that kind. Why isn't it? Because to create is to bring something forth from nothing. We humans can bring forth only from materials that are already available. We can bend the givens of human nature this way or that, but we cannot give ourselves new givens. Even if we could give ourselves new givens, the choice of which givens to give ourselves would be conditioned by what had been given before. To put this another way, if you ask a human being "What would you wish to become, if you could become anything you wished?", then his answer will be conditioned by the fact that he is now a human being. He may ask to have nonhuman attributes -- like the ability to fly -- but he will never ask to have attributes that a human being finds unattractive. I suppose you know the story about Friedrich Nietzsche and the dust of the earth. And the dust of the earth? No. Tell it to me. Nietzsche says to God, "I too can create a man." God says to Nietzsche, "Try." Nietzsche takes a fistful of dust and begins to mold it. God says, "Disqualified. Get your own dust." I don't see the point. It's just what I was saying. We can't really create. That's why, as C.S. Lewis explained, the so-called new moralities are never new. All they ever do is distort something they have borrowed from the old morality. What do you mean by the "old" morality? Conventional mores? Not exactly. The natural law. Give me an example of a new one. We've already had one -- your new morality of will. A person's choices certainly deserve some respect. But you blew this up into the principle that a person's choices deserve absolute respect. In its name you denied every other moral consideration whatsoever. I'm still not convinced that I was wrong. Give me another example. Certainly. The old morality commands compassion and prohibits murder. The new morality of euthanasia justifies murder in the name of "compassion" -- a bogus compassion which doesn't care how the painful sight is made to go away. Just as in the other case, a single precept is first distorted, then wielded against the rest of moral law. So you think these new moralities fob off picking and choosing as creating. Exactly. They don't make something from nothing; they choose and pervert an element of what is already there. But human beings do create morality. What else do you think culture is? Culture doesn't create new frameworks of moral possibility. It discovers, elaborates, and makes choices among possibilities within a framework already given. Or -- if it goes bad -- then it fights that framework, but even then it doesn’t create a new one. A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 7

|

A New Twist on Conspicuous ConsumptionFriday, 05-22-2015

According to the law of demand, the higher the price of the product, the less is consumed. In his 1899 book Theory of the Leisure Class, progressive economist Thorstein Veblen tweaked the noses of his colleagues by suggesting that this isn’t always true. Up to a point, the amount of prestigious items consumed by the wealthy may increase as the price goes up. He called this “conspicuous consumption” – buying to show off. Today we have a new twist on conspicuous consumption: Buying to show off not just how fashionably wealthy you are, but also how fashionably virtuous you are. Almost always the supposedly more virtuous products are more expensive too, so the two kinds of flaunting are combined. Moviegoers in upscale theatres snack on edamame instead of greasy popcorn, showing how virtuously they take care of their bodies. Drivers of upscale cars purchase all-electric vehicles, showing how virtuously they take care of the environment. Activists who zip from engagement to engagement in jet planes buy carbon offsets, showing how virtuously they atone for their guilt. In one of the ironies of history, progressivism has become a fetish of the comfortable, and the people who most conspicuously practice the new form of consumption are Veblen’s ideological heirs. But it is all highly selective. You won’t find many people spending money to show off their chastity, modesty, or humility. That would be tacky. Tomorrow: A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 6 of 10

|

A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 5 of 10Thursday, 05-21-2015

All this talk about "conscience" is rot. Moral beliefs are pumped in from outside. Some people never acquire any at all. You mean the famous "people without a conscience." But there is a difference between guilty knowledge and guilty feelings. Not everyone feels guilty for murder, but everyone knows murder is wrong. Precisely because they have guilty knowledge, wrongdoers who lack guilty feelings show other telltales, such as depression, a sense of defect, a compulsion to rationalize, or a puzzling desire to be caught. The suicide rate among sociopaths is also higher than in the general population. So maybe we do all have conscience. But I still think it's pumped in from outside. If I want to teach Billy that hurting people is wrong, I just say "Billy, don't hurt people. It's wrong." That's a very good thing to tell him, and I strongly recommend it. But what do you say when he asks "Why is it wrong?" I say "It just is." So do I, but that's just my point. The reason you can draw that fact to Billy's attention is that once his attention is drawn to it, he can see it for himself. But suppose he didn't. Suppose he didn't even know the meaning of wrong. What would you do then? I'd tell him "Wrong is what you ought not do." By itself that would teaches him only that "wrong" and "what you ought not do" mean the same thing. It wouldn't teach him what same thing they meant. If he already knows what "ought not" means, then you've given him a synonym. If he doesn't know what "ought not" means, then he doesn't know what "wrong" means either. In that case I'll tell him "Wrong is what you'll be punished for." Come now, you don't believe that yourself. Generally speaking, wrong should be punished. But if a wrong goes unpunished, does that mean it isn't wrong after all? Point taken. I'll teach him "Wrong is what you OUGHT to be punished for." Then you've merely led him in a circle: Wrong is what it would be wrong not to punish him for. You've explained wrong in terms of wrong. The explanation presupposes the thing you are trying to explain. Then how do you teach him what wrong means? We can teach first principles in a sense, but we can't "pump them in." The mind is so designed as to acquire them on its own, as the eye is designed to see on its own. What we call teaching only helps the process along. When we instruct and discipline the child we are only calling his attention to the first principles, giving him words for them, building on them, extending them, and reinforcing them with praise and punishment. Billy learns the meaning of the word "red" because whenever something is red, I say "red." He learns the meaning of the word "same" because whenever two things are the same, I say "same." And he learns the meaning of the word "wrong" because whenever something is wrong, I say "wrong." But a child without the rudiments of synderesis could not be taught the meaning of the word "wrong" for the same reason that a child without sight could not be taught the meaning of the word "red" and a child without the power of comparison could not be taught the meaning of the word "same." The child has to be able to see for himself what I am drawing to his attention. A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 6

|

Why I Think Pope Francis Should Rethink How He Talks to the CultureWednesday, 05-20-2015

Video of Marvin Olasky Interviewing Me Comment from a student: "The Pope is thought to be pretty progressive. Has he softened the Church’s stance on moral issues?” Pope Francis believes what the Church has always believed, but I think he may be trying too hard to say it nicely. The problem is that true love desires our true good. If what we want isn’t our true good, then what true love wants for us sounds harsh no matter how you put it. If you overdo the soft words -- “Who am I to judge?” -- people think you have softened the doctrine itself -- “He’s saying it’s not wrong.” A convert I know from the time of John Paul II’s papacy says that before her conversion, “I asked myself what the true Church would look like. She would tell the truth, and the whole world would hate her for doing so. When I looked at the Church, that’s what I saw.” Tomorrow: A Dialogue on Natural Law, Part 5 of 10

|