The Underground Thomist

Blog

So Full of SleepTuesday, 09-02-2014

Philosopher David Benatar made ripples several years ago with his book Better Never to Have Been. The author maintains that in view of the pain, disappointment, anxiety, and grief of life, our parents did us harm by bringing us into existence. Some might say that Benatar’s argument takes utilitarianism to its logical conclusion. Others might view it as bringing this dreadful doctrine to its just deserts. In the spirit of Pascal, Pensées, sec. 194, I think we might think of Benatar as follows. The poor man does not know who made him, what the world is, or what he is himself. He does not know why he has been placed in this point in the chasm of space rather than in another, or why he has been assigned to live at this moment in eternity rather than in all the ages that have come before and may come after him. He does not know what his body is, nor what his mind is, nor even that part of him which reflects on all these things and is as ignorant as they. In this condition of dread, he reflects that not all our earthly joy can sponge away a single sorrow. Yet, finding himself at this final extremity, at the end of all things, what is his response? Can a greater folly be imagined? For does he, with every resource he commands, seek to learn what the riddle means? Does he pursue the fleet prey of the solution with even as much diligence as a hound lends to chasing a coon? No, he does the lazy thing. He writes a book. Lining it with his despair about living, he fills it with mitigating advice, such as to abort one’s children early. Curiously, along the way he finds that even though life is full of tears, he does not want to die. Yet not even this most wondrous and luminous clue is enough to rouse him from slumber. Dante, who midway upon the journey of his life had found himself in a dark wilderness, understood the plight well. How I had entered, I can’t bring to mind, I was so full of sleep at just that point when I first left the way of truth behind. -- Translation of Inferno, Canto 1, lines 10-12, by Anthony Esolen |

The Thought That Stops ThoughtMonday, 09-01-2014“There is a thought that stops thought. That is the only thought that ought to be stopped. That is the ultimate evil against which all religious authority was aimed. It only appears at the end of decadent ages like our own .... “Man, by a blind instinct, knew that if once things were wildly questioned, reason could be questioned first .... “We know now that this is so; we have no excuse for not knowing it. For we can hear scepticism crashing through the old ring of authorities, and at the same moment we can see reason swaying upon her throne. In so far as religion is gone, reason is going. For they are both of the same primary and authoritative kind. They are both methods of proof which cannot themselves be proved. And in the act of destroying the idea of Divine authority we have largely destroyed the idea of that human authority by which we do a long-division sum. With a long and sustained tug we have attempted to pull the mitre off pontifical man; and his head has come off with it.” -- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, Chapter 3 |

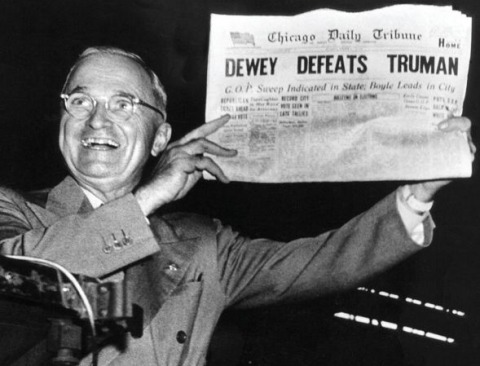

Stop the Press: Blog Gets FaceliftSunday, 08-31-2014

Hoorah! The blog has been redesigned with all the features readers have been asking for. You can subscribe, you can find the posts you’re looking for, you can link to them, and in general everything works better. The RSS link is in the horizontal menu bar up above. If you prefer, you can use the link in the footer. The main page now lists only the seven most recent posts. At the bottom, you’ll find a pager for clicking to previous weeks. If you look underneath the pager, you’ll also find a link to a list of all posts. You can have them listed either by name or by date, and in either ascending or descending order. |

What Philosophy Is ForSunday, 08-31-2014“The study of philosophy is directed not toward knowing what men may have thought but toward knowing what is true.” -- Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Aristotle’s De caelo et mundo (trans. by James V. Schall, S.J.) |

The Basic Good of Religion (So Called)Saturday, 08-30-2014

If religion means pursuing our ultimate final end, who is God, then it is He who is the “basic good,” not religion. The goodness of a means is borrowed from the end that it serves. A religion that perverts the capacity to seek our ultimate final end by turning us away from God instead of toward Him is not a lesser good – a lesser participation in “the good of religion” – but an actual evil. For that is what evil is: A privation or disorder in something that would otherwise have been good. The reason why liberty within the bounds of a just public order must be granted even perverted religions is not that they too are good, but that without such liberty we lack even the chance to discover our errors without misdirection from tyrants. While we are at it, let us consider the Godward longing that moves us to participate in religion. Certainly this longing has a nobility of its own. Lesser creatures are not capable of it; we have it because we are made in the image of God. But the perversion of the best is the worst. When a pro-abortion demonstrator at the Texas state capitol was caught on video sardonically saying “Hail, Satan,” it was not a moment of diminished nobility but a horror. Basic goods theory holds that none of the goods it considers basic is more important than any other, just because none of them is a means to any other. For example, it holds that neither play nor friendship is more important, because play is not merely a means to friendship, nor is friendship merely a means to play. But this is a non sequitur. From the premise that one thing is not a means to another, it does not follow that neither is more important. Thomas Aquinas held that the fact that God is our ultimate final end is demonstrable by reason. If this is true, then seeking Him is plainly most important. Revelation concurs: “Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things shall be yours as well.” |

Question for Grad StudentsFriday, 08-29-2014You propose to become a professional scholar. Unless you are independently wealthy, your ability to do so will depend on the expenditure of other people’s wealth (in the form of tuition, taxes, or patronage) to pay your salary. What reason can you sincerely give for what you want to do, sufficient to justify such expenditure? Consider possible objections. Discuss thoroughly. |

Universities as Money LaunderersThursday, 08-28-2014

Universities are converting themselves from institutions of learning into money launderers. As conduits for grants and endowments, and as honeycombs of “centers” and “institutes” where activities are conducted which cannot be carried out in conventional departments organized by discipline, they offer both Left and Right a thousand ways to transfer wealth while hiding the precise nature of who and what is getting it. Liberals, working mostly through the crumbling shell of what used to be the liberal arts, use universities to transfer wealth to unpopular left-wing causes which would have a hard time sustaining themselves on their own. Conservatives, working mostly through the sciences, use universities to enable business enterprises to reap the benefits of new technology without having to invest as much in research and development. And then there are those who don’t really care who gets the benefit, as long as the Great Nile of other people’s money is diverted from other regions and universities into their own. |