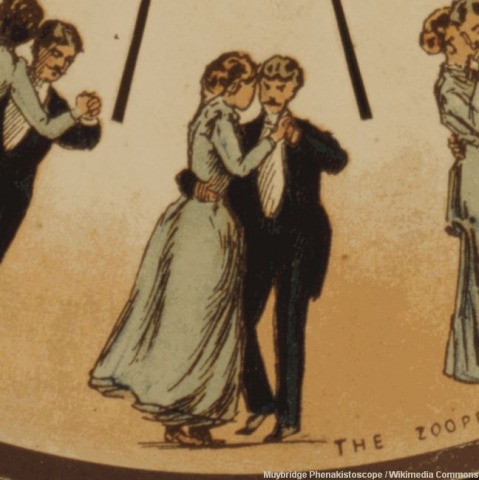

To see the dancers in motion,

click here or click the image

A man who cannot keep an appointment is not fit even to fight a duel. -- G.K. Chesterton

I published the following article in The National Review in 1995, during the Clinton Administration. Considering how the tendencies I described have not only accelerated since then but even been applauded on both the left and the right, I thought it might be timely to re-post it here. I have resisted the temptation to update the references.

+++++ + +++++

Good manners seem to be taking it in the chops lately. Consider only rudeness. College students blatantly read newspapers in class. Columnists in these newspapers call the First Daughter ugly. The President calls Rush Limbaugh fat. Rush Limbaugh defends a liberal for calling women broads. Women give men dirty looks for opening doors. Panhandlers gather around the doors to insult passersby. Passersby sport T-shirts insulting panhandlers. Auto bumpers sport stickers telling other drivers what they can eat if they don't like how the owner is driving. Drivers steal parking places from other drivers. The other drivers make crude gestures because they are trying to get to their assertiveness training class. The class starts late because the teacher is never on time.

Discourtesy, ingratitude, boorishness, and indecorum are now so much expected in public life that one begins to make sport of them. At any televised awards ceremony, odds are good that one of the following things will happen: One of the recipients will abuse the presenters; one of the presenters will abuse the recipient; either a presenter or a recipient will abuse third parties not present; or the proceedings will be disrupted by demonstrators. Place your bets.

Could the decline of good manners be a sign of progress? Some people think so:

The ultimate value is authenticity, but good manners are inherently inauthentic. Only a hypocrite feigns what he does not feel. Don't I have to be me?

The ultimate value is equality, but good manners are inherently inegalitarian. Only a fool defers slavishly to age, authority, or the female sex. Aren't I as good as you?

Good manners make a fetish of the form of conduct while ignoring its goal. Sometimes a speaker should be shouted down without a hearing, and sometime he shouldn't. Doesn't it all depend on whose ox is being gored?

Bad manners are a way of blowing off steam. They give people a way to settle their scores without resorting to violence. Repression merely invites a bigger explosion later. Isn't a rude word or a slammed door better than a punch in the head?

Finally there is the argument I call, with apologies to the Vatican, the "preferential option for the poor":

Demanding good manners is merely a way of keeping down the disadvantaged. They can't join your mannerly debates because they haven't got the education. To ban the use of shouting, vandalism and obscenity is to ban their only way of getting your attention. Aren't you really telling them, "Shut up?"

Although the preceding arguments come from the cultural left, the assault on courtesy finds echoes on the right as well. Consider an example. The fall of chivalric or gentlemanly courtesy has had the predictable consequence of weakening men's sense that women are to be protected instead of preyed upon. Unable to recognize the true sources of the problem, feminists now make it worse by defining men as predators: Marriage is slavery, intercourse is rape, courtesy subordinates, compliment is sexual harassment, accusation is presumptive evidence of guilt, and so on. Sometimes, in satirizing these fanatics, we miss an opportunity to rake up the embers of the older ideal. In order to reestablish the propriety of appreciating female beauty, for instance, the most talented rhetorician in conservative ranks humorously calls attractive women "babes" and pretends to transmit "mental orgasms" to them. As intended, this outrages feminists. But it also outrages ladies. If I were privileged to advise Mr. Limbaugh, I might speak to him as follows. A lady does not, like a feminist, expect us men to cut off our organs of generation. But she rightly expects us not to speak as though our organs were always erect. By an in-your-face defense of conduct that violates the code of gentlemanly courtesy, we merely deepen its disrepute. We lose sight of the same thing that the feminists do.

For these and many other reasons we find that courtesy and good manners need more than teaching and reinforcement today. They need an intellectual defense. If we cannot make a moral case for manners, we had better give them up. Has the exercise any point? I think so. Obviously, some people are beyond reaching, but most do not fit in this category. Some of the young have good intentions, but are baffled by the culture and are trying to figure things out. Some of the grown have figured things out already, but could use a reminder. Some of the rest of us need answers for barbarian colleagues who demand reasons for what ought to be obvious. And some of us simply need to have our spines stiffened before we face our children. Why must I write Grandma a thank-you letter? She knows I got the present, and I didn't like it anyway. You don't want me to lie, do you?

In brief, then, here is what might be called the theory of manners, which is part of the applied theory of virtue.

Becoming better than we are. Good manners are a species of custom. Courtesy is the virtue that concerns them. This virtue finds its initial place in a world in which people are flawed in virtue generally, but would like to be better than they are. For courtesy has two interesting properties. One is that because it has more help from custom, it requires less exertion of judgment than some of the other virtues and is therefore easier to learn. The other is that up to a point, it pulls some of the others along. It incubates them, providing a protected environment in which they can grow.

The sincerity of pretense. Here is how this incubation works. As I am now, I want what I ought not want, and I do not want what I ought to. My feelings are at war with the person I want to be. One of the things I do about this is wear a mask, just as beautiful as I can make it. Masks, of course, can be used to deceive, but in courtesy that is not the aim. As C.S. Lewis, Gilbert Meilander, and others have explained, I wear the mask partly in the hope that my true face will gradually grow to fit it, and partly in the hope of not setting a bad example in the meantime. "If you please," "thank you," and "the pleasure is mine" may be mere formulae, but they rehearse the humility, gratitude, and by grace, even charity, that I know I ought to feel and cannot yet.

Playing along. Good manners concern not only my mask, but yours. Though I may not have sense or self-knowledge enough to recognize all of the bad habits by which I make life unnecessarily difficult for you, even a well-meaning clod knows some of the counsels of courtesy because they are taught to him by custom. I should not be late for my appointments; that risks provoking you and making your mask slip. If you are my customer, I should not use your first name as though you were my fishing buddy; we need to remember which masks we are wearing because differences in station dictate differences in duties. If I am a woman, I should not wear a party dress to work; that is both confusing and provoking, because the ambiguity annoys. Out of context it seems to be a come-on. Can one wear two masks at once?

The golden mean. Even with the help of custom, some judgment is necessary to the practice of courtesy, because customs are rules that work only in most cases, and there are always exceptions. Thus, more than just a habit of following good manners, courtesy is a developed ability to adapt them wisely to place and time in a way that preserves their intention. In this it resembles the other virtues. As courage finds the mean between the cowardly and the rash, friendliness finds it between the cool and the codependent, and tolerance finds it between the narrow and the overindulgent, so courtesy avoids two opposite mistakes: On the one side rigidity of manners, on the other side carelessness.

Celebration. All this talk of avoiding opposite vices may seem depressing. But we need not be somber about courtesy. Really well done, good manners not only rehearse the ideal of virtue but anticipate and celebrate it, much the same as ballroom dancing celebrates the ideal of marriage. In both there is a playful, shifting counterpoint of speech and movement in always mutual, yet always asymmetrical submission. "May I?" "Please go on." "Shall we?" "By all means." Step, step, step, turn. Among the saints, rehearsal would be nothing, celebration everything; courtesy would be a mode of frolic sanctity. There is a glimpse of that in every courteous smile.

So armed, can we reply to the debunkers? Yes: Not necessarily to their satisfaction, but at least to ours.

As to the argument that good manners are inauthentic: There are two mistakes here. The small one is that every kind of mask is meant to deceive, and we have already seen why that is false. Behind this small error is the larger one of thinking that being myself is a thing of great value. In fact it has hardly a value at all. Only by losing my life will I save it; only by forgetting about being myself will I find out who I was meant to be. It will be objected that this is a religious answer. That I cannot help; it happens to be true. Anyway, Authenticity is a religion too. It is just not a particularly attractive one.

As to the argument that good manners are inegalitarian: So they are, root and branch. And there is a grain of merit in thinking this smells fishy. Humility is necessary for everyone, because we share in both the dignity of being made in God's image and the shame of not acting like it. Here the equality of grace might begin; but here the equality of nature ends. We do not all have the same strengths, weaknesses, experiences, or stations. By pretending that we do, we lose the only ground on which we can support or make claims on one another. One cannot build an arch from identical bricks.

As to the argument that manners depend on whose ox is being gored: At least the debunker is right in one point. Not only in arms but in ideology, there is a time for war and a time for peace. But if we are to speak of war, let us speak of Just War: There must be justice not only in the cause, but also in the way of waging it. Adapted to ideological warfare, the principles for waging war justly are as follows. First is right intention. The aim of those who war for truth should be agreement in the truth; therefore, they should avoid any acts that would hinder ultimate conversion. Second is proportionality. Combatants should avoid tactics that do more harm to truth in general than good to the particular truth that is at issue; therefore, they should use no force but the force of better argument. Third is discrimination. Deliberate attacks on non-combatants are impermissible; therefore, not only the speakers but the audience should be respected.

As to the argument that discourtesy blows off steam: This line of reasoning works no better in the debate over manners than in the debate over pornography, for one bad deed may be catharsis, but a series of bad deeds is merely practice. The only way that slamming a door blows off my wrath is by indulging it. By failing to practice self-control I grow less and less able to exert it. Instead of growing to fit a beautiful mask, my face freezes in the expression of hell.

As to the "preferential option for the poor": No point that requires shouting, vandalism, or obscenity for its expression is worth hearing. If the poor really lack the education to get one's attention without such means, truer justice would be to educate them. Does the debunker believe they are incapable of education, or does he believe they are incapable of courtesy? Which side here shows them greater respect?

One hears that people today have bad manners because they are too wrapped up in seeking what is good for themselves. I don't think they care too much about the Good; I think they care too little. Bodily and external goods are nearly worthless without the goods of character, for then, once our comfort has been secured, the rest of our lives is blown away in spume and eaten up in vexation. I said before that courtesy finds its initial place in a world in which people are flawed in virtue generally, but would like to be better than they are. The dance of courtesy is interesting only to those who have discovered the romance of virtue.