The Underground Thomist

Blog

Defying the Natural LawMonday, 04-13-2015

I’m breaking my “Monday for students” rule again. This letter is from an attorney in Jamaica. Query: Why is it that we humans find nothing wrong in defying physical laws, for example by flying, yet we do consider it wrong for us to defy moral laws? Just thinking. Also, doesn’t the fact that some people have defended slavery as "natural" show that we cannot be certain about the content of natural law? Reply: I’m glad to answer. There are two mistakes in the way you pose your first question. The first mistake is that we don’t defy violate natural forces; we only make use of them. When an airplane flies, it responds to a number of forces at once. Gravity pulls it down, lift raises it up, and thrust drives it forward. The motion of the airplane is the resultant of all of these forces together. The other problem is that you are mixing up natural forces with natural laws. A law is a rule and measure of right and wrong, suitable to guide the acts of a free and rational being. From this point of view, “Never murder” is a natural law, but gravity isn’t a law; it is merely a natural force. When we call gravity a “law,” we are speaking analogically, because the airplane is not thinking to itself, “Golly, I am in a gravitational field – I ought to fall down.” We see then that the original form of the question has things backwards. The airplane cannot defy the force. But a rational being can defy the precept – although it shouldn’t. As to your second question: Some pre-Civil-War American masters defended the enslavement of black Africans on ground that the slaves were naturally inferior. They were gravely mistaken. So doesn’t that show that we can’t be sure about right and wrong? No, it shows just the opposite. After all, if you weren’t sure that slavery was wrong, then how could you call them mistaken? It is only about real matters of fact that it is possible to make mistakes – and it is only about real matters of fact that it is possible to correct these mistakes. You wouldn't say that since physicians once mistakenly believed that bloodletting could cure everything from cancer to acne, therefore we can never be sure that it doesn't. Or that since astronomers once mistakenly believed that there were canals on Mars, therefore we can never be sure that they don't exist. Or that since surgeons once operated without washing their hands, therefore we can never be sure about the benefits of asepsis. So why should you worry that since some slaveowners once tried to convince themselves that Africans were natural slaves, therefore we can never be sure that they aren't? Tomorrow: On Not Letting Facts Get in the Way

|

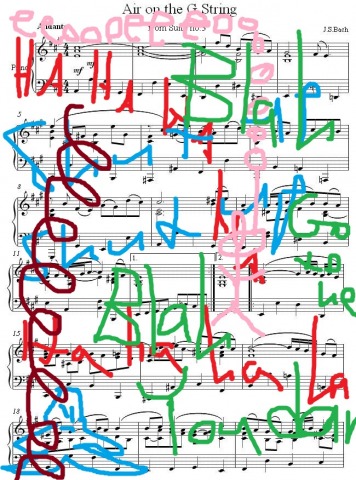

A Word to the WiseSunday, 04-12-2015

Friedrich Nietzsche, the philosopher of will to power who originated the motto “God is dead,” wrote, "I think of myself as the scrawl which an unknown power scribbles across a sheet of paper, to try out a new pen" (letter to Peter Gast, August, 1881). He was not the only one. It seems that in our age a number of new pens are being tried out – in politics, literature, music, culture, mendacity, disgrace, and oppression. A day is coming when the scribble will seem to fill every inch of every sheet, every placard, every wall. And yet it will not prevail. Tomorrow: Defying the Natural Law

|

What Feminism Has Achieved for WomenSaturday, 04-11-2015

“Ten million young women rose to their feet with the cry, ‘We will not be dictated to,’ and went off and became stenographers.” -- G.K. ChestertonTomorrow: A Word to the Wise

|

Edward Rubin’s New MoralityFriday, 04-10-2015

The rise of the view that “it’s all about me” is commonly viewed as a decline in morality. Vanderbilt law professor Edward Rubin says that’s all wrong. He writes in his new book Soul, Self and Society: The New Morality and the Modern State that we aren’t seeing a decline in morality, but merely the rise of a new morality. This new morality turns out to have just as many rules and prohibitions as the old one. For example – this is Rubin’s example, not mine – one must not express disapproval of the sexual behavior of anyone else, or one will be punished by those in authority. Well, yes, I suppose one can call such a thing a new morality. And yes, I agree, it is strenuous and burdensome. If anything, this dreary code of correctness has more taboos than the old one, and its strictures are not gates of life, but portals of death. But why stop with one new morality? The possibilities are endless. Abortion is the token of a child-free morality. Wife-beating expresses the exuberance of a morality of male empowerment. Theft is the anthem of a morality more open to the sharing of wealth. I do think Rubin misrepresents the old morality. He writes as though fulfillment is something new in the history of ethics. Poppycock. Aristotle wrote that ethics is about human flourishing; St. Thomas Aquinas wrote that the ultimate goal of human life is that complete and final happiness which leaves nothing further to be desired, which turns out to be the vision of that God whom we naturally love more than ourselves. The really distinctive mark of the so-called new morality isn’t its insistence on fulfillment, but its confusion of fulfillment with self-indulgence. But that’s not really new either. The old-fashioned word for it is “sin.” Tomorrow: What Feminism Has Achieved for Women

|

That Makes Everything OkayThursday, 04-09-2015

There have always been people who believed that happiness is having expensive toys. But there has been a change: “I bought a Keaton Batmobile in 2011,” writes one 52-year-old man in the Wall Street Journal . “It’s a movie prop; it was used as the stand-in-car in the filming of the 1992 Warner Bros. movie ‘Batman Returns,’ starring Michael Keaton. I put a Corvette engine in it and re-engineered things so it’s drivable and safe. It has blinkers, taillights, and five cameras in it so you can see everything around you. With all the upgrades, I easily spend a half-million dollars on it .... In the past few years, no matter what troubles have come along – business problems, divorce problems – I always think: Yeah … but I own the Batmobile! And that makes everything OK.” Two generations ago, people flaunted their wealth, but never their immaturity. If they weren’t grown up, they faked it. They were embarrassed to be known for being shallow. Now they expect applause for it. Triviality is not their bane, but their ambition. Tomorrow: Edward Rubin’s New Morality

|

Opinions of Dead MenWednesday, 04-08-2015

Why do we have constitutions, anyway? Are we merely paying reverence to the opinions of dead men? No. The point of a constitution is not that the people who wrote it are necessarily wiser than we are, but that (a) we wish to be ruled by known laws, rather than by the fleeting whims of those who hold power at the moment, and (b) the fundamental design which limits the laws should be much harder to change than the laws themselves. Constitutions shouldn’t be impossible to change: That’s why there are procedures for constitutional amendments. But change should be difficult. If the constitution is treated as a “living document” the meaning of which can shift and flow in the light of “evolving standards,” then it is no longer functioning as a constitution, and there is no reason to keep it. On the other hand, written constitutions pose a different kind of problem. Since they are viewed as a kind of law, they tend to be interpreted by courts, and since they are viewed as a higher kind of law, courts suffer prodigious temptations to act as superlegislatures -- destroying the constitutional scheme in the very name of saving it. Although the Framers of the U.S. Constitution were unusually talented men, they were naive about this possibility, assuming that the judiciary would be the weakest branch of government, and the legislature the strongest. They would be dismayed and confounded by the extent to which Congress has ceded its authority to the courts and the executive. Tomorrow: That Makes Everything Okay

|

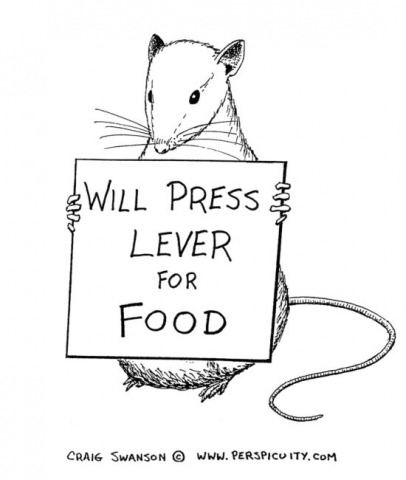

Life in the Rat CageTuesday, 04-07-2015

I have been reading some of the work of the late radical behaviorist B.F. Skinner. Skinner, who denied free will, seems to have drawn some of the implications of his position – but it seems to me that he stopped short. Read the following remarks, from his autobiography and to the interviewer Alfie Kohn, and see whether you agree. “I am often asked, ‘Do you think of yourself as you think of the organisms you study?’ The answer is yes. So far as I know, my behavior at any given moment has been nothing more than the product of my genetic endowment, my personal history, and the current setting.” “During the ‘Dark Year’ in Scranton, I began to write notes about intellectual suicide .... I did not consider actual suicide; behaviorism offered me another way out: It was not I but my history that had failed.” “I have continued to seek relief from the effects of punitive consequences in the same way. I have learned to accept my mistakes by referring them to a personal history which was not of my making and could not be changed.” “When I finished Beyond Freedom and Dignity, I had a very strange feeling that I hadn’t even written the book. Now I don’t mean this in the sense in which people have claimed that alter egos have written books for them and so on, but this just naturally came out of my behavior and not because of anything called a ‘me’ or an ‘I’ inside.” “If I am right about human behavior, I have written the autobiography of a nonperson.” “I can now take all of my faults and all of my achievements and turn them over to my history, and the point I make is that when I die personally, it won’t make a bit of difference. Because there’s nothing here, you see, that matters.” “I never think much about dying. I have no fear of death .... The only thing I fear is not finishing my work. There are things I still want to say.” Having once thought much the same way myself when I was a young man, I am in no position to be snarky. But isn’t it self-defeating to say “I don’t have an I”? If the speaker doesn’t have an “I,” then who is denying it? If nobody is denying it, then has it really been denied? If the self who seems to deny it is an illusion, then who is suffering the illusion? And by the way, if this nonperson isn’t worried about his extinction, then why does he worry about the extinction of his work? For since the rest of us are nonpersons too, there will be no one to appreciate or understand it. Tomorrow: Opinions of Dead Men

|