The Underground Thomist

Blog

The Staircase of LiesWednesday, 04-22-2015

The increasing filthiness of our national politics brings to my mind a question put to me a long time ago by one of my own teachers. "Don't you think there is more lying in politics than there used to be?" he asked. "Why do you think that this is happening?" At the time, young oaf that I was, I thought his question silly. But after thinking lo these many years, I would like to try to answer it. Our statesmen do lie more, and for the same reasons that most of us lie more. There are seven degrees of descent on the downward staircase of mendacity. Not all of us are at the bottom, but most of us are at a lower stair than we admit. The first and topmost stair is simply sin. The greater our trespasses, the more we have to lie about. We lie about money, sex, and our children, because we sin about money, sex, and our children. A turning point in both public and private life came in the early seventies, when we legalized the private use of lethal violence against babies yet unborn. The justification of such staggering betrayal takes more lies than there are words to tell them. The second stair is self-protection. Lies are weaklings; they need bodyguards. Even the smallest prevarication needs a ring of perjuries to keep from being seen. But each new lie needs its own protective ring. Pretty soon the liar is smothered in layers of mendacity, as numerous as onion shells, as thick as flannel blankets. Third down is habituation. We make habits of everything; it is part of our nature. Courage and magnanimity become habits, and so does the chewing of gum. In time lying too becomes a habit. After you have lied awhile for need, you begin to lie without need. It becomes second nature. You hardly notice that you do it. Asked why, you can give no reason. You have crossed the border between lying and being a liar. Underneath the previous stair is self-deception, for beyond a certain point, a person starts losing track of truth. Your heart cannot bear to believe that you lie as hugely as you do, so to relieve the rubbing, itching, pricking needles of remorse, you half-believe your own fabrications. Rationalization follows next in order. As your grasp on the truth continues to weaken, you come to blame its weakness on truth itself. It's so slippery, so elusive, who can hold it? It changes shape, moves around, just won't sit still. Not at all fair of it, but everything is shades of gray anyway. How silly to believe in absolutes. Truth is what we let each other get away with, that's all. Sixth comes technique. Lying becomes a craft. For example, you discover that a great falsehood repeated over and over works even better than a small one. Nobody can believe that you would tell such a whopper; therefore, you have a motive to make every lie a whopper. This technique, called the Big Lie after a remark in Hitler's Mein Kampf, is not a monopoly of totalitarian dictators, or even of politicians; probably no one uses it in public life before he has practiced it in private. Our American variation on the Big Lie works by numbers instead of size. If you lie about everything, no matter how small, nobody can believe you would tell so many lies. The whistleblowers exhaust themselves trying to keep up with you, and eventually they have blown their whistles so many times that people think that they must be the liars. By the time a few of your lies are found out, the virtue of honesty has become so discredited that no one cares whether you are lying or not. "They all do it." The seventh and bottommost stair is that morality turns upside-down. Why does this happen? Because the moment lying is accepted instead of condemned, it has to be required. If it is just another way to win, then in refusing to lie for the cause or for the company, you aren't doing your job. This is where we are, and this is who we are becoming. The problem is not just in our politicians, for they came from us and we elected them. How serious are we about Truth? Do we dare finally yield our hearts, words and deeds to to be scraped, scoured and made honest until they can give back His light? Tomorrow: The Permanent Advantages of Good and Evil

|

You Read it Here FirstTuesday, 04-21-2015

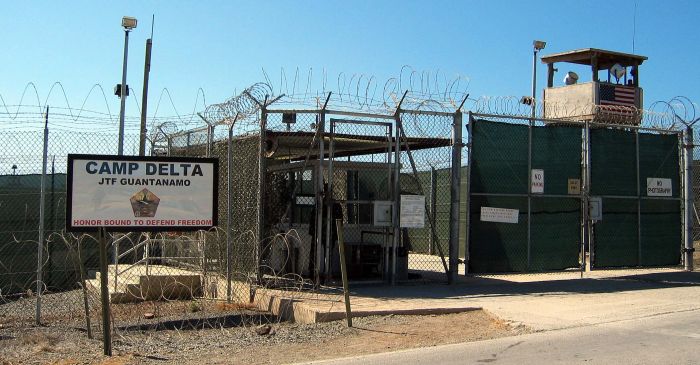

This isn’t a current politics blog, and it’s not going to become one. Every now and then, though, I can’t resist. The puzzle about the administration’s drive to normalize relations with the Cuban thug regime isn’t why it is happening, but why it is happening now. The president has been in office for six years. If normalizing relations with the Communists is so important to him that he’s willing to take the flak, why didn’t he push for it earlier? I don’t think he cares much about normalization for its own sake. He does care about closing Guantánamo Prison and transferring or releasing the detainees -- a campaign promise he has been unable to keep. Normalizing diplomatic relations is a lever. So in coming days, keep your eyes on the headlines: CUBA DEMANDS RETURN OF GUANTÁNAMO BAY AS CONDITION OF NORMALIZATION. You read it here first. Tomorrow: The Staircase of Lies

|

The Sabbath and Natural LawMonday, 04-20-2015

This letter comes from a doctoral student and professor in a seminary in Spain. Question: Amongst our small faculty there is discussion concerning the relationship between natural law, the Ten Commandments, and the issue of the Sabbath. It is my understanding that the Ten Commandments are a summary of the natural moral law. However, we know that since the resurrection of Jesus, the “holy day” has changed from Saturday to Sunday. My questions are the following: If the Ten Commandments summarize natural law, then what day does the natural man “know” to be the day of rest/worship? Or has natural law itself changed with the coming of Christ? Do you personally exclude Sabbath worship from natural law? Reply: Thank you for writing. Here is how I understand the matter. (By the way, my favorite saint discusses all these things in much greater detail in Summa Theologiae, I-II, Questions 98-108.) Old Testament law contains several different kinds of precept: Moral precepts, such as the prohibition of murder; ceremonial precepts, such as the prohibition of mixing different kinds of fibers in the same garment; and judicial precepts, such as the rules about how many witnesses are necessary to convict someone of a crime. All of the moral precepts of the Old Testament law coincide with the natural law. They would have been knowable by reason alone, even apart from divine revelation; they bind universally and without exception; and they cannot be changed. The ceremonial elements in Old Testament law could not have been worked out by reason alone, so they depend on divine revelation. Although they held for the people of the old covenant, they do not hold universally, and they can be changed by divine authority. If taken not just in their words, but together with what they imply, suggest, and presuppose, the moral precepts of the Ten Commandments do summarize the natural law. For example, the commandment against adultery presupposes the institution of marriage, which is the unique setting for the practice of the sexual powers. Although it explicitly prohibits only one form of sexual impurity, this has always been understood as a placeholder, or metonymy, for all sexual impurity is wrong, but adultery is the most conspicuous example. The fact that the moral precepts of the Ten Commandments summarize the natural law does not imply that everything in the Ten Commandments is a moral precept. For example, we can analyze the commandment about the Sabbath into two elements, one moral, the other ceremonial. The moral element is that times and places be set aside for remission of labor and worship of God; this is a part of the natural law, and everyone should do it. The ceremonial element is that one of the times to be set aside be the seventh day; this command, which is not part of the natural law, was given to the old covenant community, but the Church by God’s guidance can make different arrangements for the new covenant community. As indeed He has, for in the new covenant community we rest and worship not on the seventh day, to commemorate God’s rest from the original creation, but on the first, to commemorate the new creation which was inaugurated with the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

|

Argument to the Best ExplanationSunday, 04-19-2015

All other things being equal, we ought to accept the hypothesis which best explains what we observe. For example, which hypothesis best explains what we actually see in the negotiations of the present administration with Iran: That the chief executive does not want Iran to obtain nuclear weapons but is incompetent at diplomacy? Or that he considers the nuclear supremacy of America unjust, finds it equitable that Iran should have nuclear weapons too, and merely has to seem to be against it? Yes, I think so too. Yet intelligent citizens consider it outrageous even to suggest the possibility. Tomorrow: The Sabbath and Natural Law |

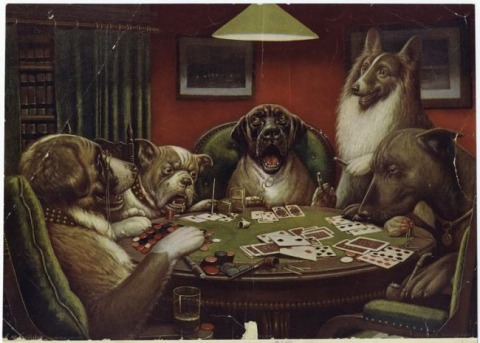

Do All Dogs Go to Heaven?Saturday, 04-18-2015

A social scientist writes, “I just read an article in Public Interest in which the philosopher Edward Feser says Thomists ‘deny there will be non-human animals in heaven.’ Now, I understand the argument that animals on earth won't be resurrected in heaven. But he seems to be saying more.” Reply: I’m not sure whether Feser intended to imply more in his fine article, but let’s review Thomas Aquinas’s argument. A soul is the formal principle, or pattern, which makes the difference between a lump of dead flesh and an embodied life. In this sense all living things have souls, but they do not all have souls of the human sort. Our souls are rational; animal souls, like those of dogs, are merely sensitive. Now everything which the merely sensitive soul does pertains to its union with the body. But the rational soul has certain purely intellectual, non-material operations which are not dependent on its union with the body, and belong to the soul in itself. St. Thomas concludes that the soul of the dog has nothing that could survive the death of its body, but the soul of a human being does. I think this argument is correct as far as it goes, but I would qualify it in two ways. First, it doesn’t preclude the possibility of heavenly animals which had never existed in this life – and I don’t think Feser meant to imply that it did. It is only about the resurrection of animals which have existed in this life. Second, it does not absolutely preclude animal resurrection. It only prevents us from saying that sensitive souls have something which could survive the death of their bodies by their very natures. So far as we know, God could gratuitously preserve them by means which exceed their natural powers – just as we believe He will raise redeemed humans to the vision of Himself by means which exceed our natural powers. We simply have no information on this point. Tomorrow: Argument to the Best Explanation |

It’s Not True Until Simon SaysFriday, 04-17-2015

Such is the chemistry of the brain that the longer that good-night hug lasts, the more it produces the feeling of a bond, even if one is thinking "this doesn't mean a thing." The lesson would seem to be that unless you are already attached, it would be a good idea to keep those hugs short. Don't blame me. Blame oxytocin. I can imagine protests. "Why didn't anyone tell me that it only takes ten seconds or so for my brain to release oxytocin? Why didn't anyone tell me that my vulnerability might be even greater in the dark?" These are the wrong questions, for such little findings of brain science merely ratify common sense. Long before people knew about neurotransmitters, they understood that it was wise not to stay out too late, smart not to turn out the lights, and good to put limits on the touching of bodies. Long before they knew that the frontal lobes aren't fully developed until about age twenty-five, they knew that young people need supervision and shouldn't be left alone. Long before they knew how the endocrine system works, they knew that exhaustion and inactivity make not only the muscles but the virtues lose their tone, so that if one doesn't want the mice of temptation to turn into ravening beasts, one must get proper sleep and exercise. Long before they had statistical confirmation from sociologists, they knew that a child needs a mom and a dad. Once upon a time, such bits of mother wit, gleaned from centuries of experience, were passed on from generation to generation. To us they seem new because we have broken the generational transmission belt and forgotten what everyone used to know. Instead of turning to our grandmothers, we turn to biochemists and statisticians. We believe the obvious only when we count it on a calculator or isolate it in a test tube. Tomorrow: Do All Dogs Go to Heaven? |

Why Can't Johnnie's Teachers Reason Either?Thursday, 04-16-2015

One of the readers of this blog asks a good question about last week’s post, “Why Can’t Johnnie Reason?”: “So, Johnnie can't reason because he wasn't taught, because his teachers didn't learn or weren't taught. It's outside the scope of a brief post to trace the causal chain back to its source, but do you have a notion of what is responsible for the flight from reason broadly speaking? Because I assume that it began as a conscious rejection rather than as an inadvertently lost skill.” That’s a tough one, but I think there are at least two great tangles or clusters of causes. One of these clusters has to do with sheer pedagogical sloppiness. The other, which has taken longer to develop, has to do with the rise of skepticism over the last seven or eight centuries. Untangling these mare’s nests will take a long, long time. Our children and children’s children will have their work cut out for them. The skepticism of our day is quite different from the skepticism of most of the ancients. When Marcus Tullius Cicero called himself a skeptic, he merely meant that he was always open to new arguments, although in the meantime he would accept the opinion for which the best reasons could be offered. Today’s more radical skepticism, which tends to deny the very possibility of knowledge, has a number of contributing causes, for example the irrationalism of Martin Luther, the vastly influential Protestant Reformer, who wrote in his last sermon in Wittenberg (1546), “But the devil's bride, reason, the lovely whore comes in and wants to be wise .... As a young man must resist lust and an old man avarice, so reason is by nature a harmful whore. But she shall not harm me, if only I resist her. Ah, but she is so comely and glittering .... Therefore, see to it that you hold reason in check and do not follow her beautiful cogitations. Throw dirt in her face and make her ugly.” But a deeper and subtler cause is what philosophers call the “epistemological turn.” The wise approach to reality taken by thinkers like Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas set things before knowledge. They approached all kinds of things this way – material objects, volitions, qualities, whatever they may be – for no matter what we are studying, we have to know something before we can investigate how we know it. But in the modern era, we reverse this procedure. Before studying what there is to know, we insist on a critique of our ability to know anything at all. Extreme skepticism is but one of the bad results of this shift. Of course even the skeptic has to assume that something is true; otherwise he has no way to decide what to do and how to live – the springs of action lose their springiness. In practice, then, extreme skepticism turns into its opposite, extreme conventionalism. For the supposed skeptic doesn’t really reject prejudice; he unquestioningly accepts every prejudice that has learned to put on skeptical airs. Pedagogical sloppiness has causes of its own. Alexis de Tocqueville drew attention to the hurriedness of modern life, which leads to an intellectual demand that everything be made easy. First, books were made easier; now, with the rise of the technologies of glibness, students are losing the very habit of reading books. Another cause is the Pragmatist educational reforms of the early twentieth century, which held that facts keep changing and the only thing worth teaching is how to learn. You would think that “learning how to learn” would include learning logic, wouldn’t you? But no, Pragmatists think that even the rules of logic are no more than useful generalizations which at some point may cease to be useful. Then there are all our destructive faux-democratic notions, for example that college should be a universal certifier (which requires dumbing it down so that even people who cannot genuinely benefit from higher education can be pushed through), and that students should evaluate their teachers (which punishes teachers who make their charges work). And let us not forget the disappearance of silence -- so that even if the student should take it upon himself to think about something, he can’t hear himself do it. Tomorrow: It’s Not Real Until Simon Says |