The Underground Thomist

Blog

Is and OughtMonday, 03-30-2015

Mondays, as always, are for questions from students. Question: I have been educated to take the naturalistic fallacy seriously, even though I thought it was a bit of bunk, because some smart and good men espouse it. You write in both popular and specialist venues. In one of your more popular articles, I notice you make short shrift of the fallacy. Do you treat it briefly because you consider it a simple, albeit serious, mistake, or just because of the audience? If it is really simple, then why do those smart and good men err? Reply: Like you, I was educated to believe that deriving an is from an ought is invalid. Just because so much has been written about why this “naturalistic fallacy” is not a fallacy, by thinkers like Peter Geach, Ralph McInerny, Anthony Lisska, and Robert Koons, I don’t think I need to explain at great length. I’ve also found that sometimes saying too much obscures the point rather than clarifying it, no matter what the venue. But I do think the error is simple. Yes, some smart and good thinkers espouse it. We all commit many errors; they would say I am committing one now. In general, to attain a single insight, one must unlearn a dozen mistakes. I say a dozen, but that’s if one is lucky. It seems to me that “Is does not entail ought” is a claim about ontology, disguised as a claim about logic. I can’t see why anyone should accept it unless he denies that things have real moral properties. In that case he will say that is statements describe facts, ought statements express attitudes toward facts, and nothing about the facts could ever make any attitudes unfitting. But this is absurd. “Seeing is the function of the eye” is an is statement. But to assert it is to hold that eyes that see well are good eyes, and eyes that see poorly are bad eyes. And since “good” means what ought to be furthered, we ought to help bad eyes see better. Again, “Arsenic is a poison” is an is statement. But to assert it is to hold that arsenic injures the natural good of health. And since evil means what ought to be avoided, we ought to keep arsenic off our tables. Christian Smith helpfully remarks, “the descriptive observation is first made that is and ought belong to different orders, from which is then derived the normative injunction that we should keep them separate. But if we really cannot get an ought from an is, where did that injunction come from?” Tomorrow: What Can I Do? I'm in Love

|

Attempt at a DefinitionSunday, 03-29-2015 |

Natural Law and Original Sin, Part 3 of 3Saturday, 03-28-2015For new readers:Introduction to the blog (2013)

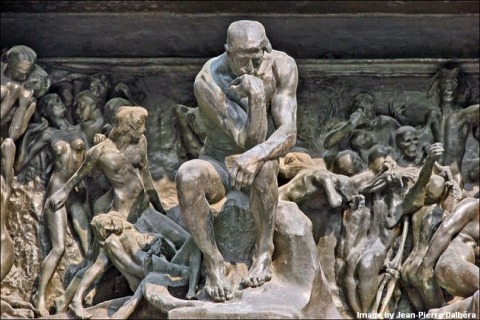

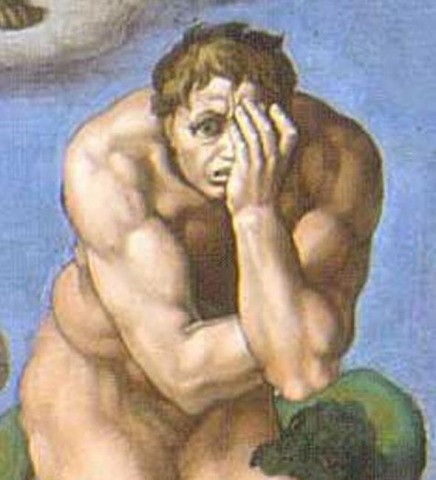

A purely ahistorical view of natural law is certainly possible. Christians, however, view our unchanging human nature in the light of salvation history – Creation, Fall, Redemption. How can something unchanging have a history? The answer is that although our nature does not change in itself, its condition can certainly change, and it does. Man was created in the condition of “original justice,” a condition of friendship with his Creator, in which he was also in harmony with his own nature, with his fellows, and with the rest of creation. Original sin is the loss of original justice – not friendship, but alienation from our Creator. The result of this loss is a habitual tendency to disorder, which afflicts human nature in much the same way that sickness afflicts the human body. Just as sickness makes the body a stranger to health, so original sin makes the soul a stranger to integrity; it destroys the original harmony and equilibrium that characterized our original condition. Once the harmony of original justice has been ruined, the various powers of the soul, which were formerly held in balance by reason, push us in different and even opposite ways. Each power of our nature turns away from the supreme and eternal good, God, toward lesser and changeable goods. At bottom, the disorder of our desires is nothing but this turning away. Specific disordered desires, such as lust, are only its manifestations. But this turning away manifests itself in other ways too. Because reason is no longer properly ordered toward truth, we suffer ignorance; because the will is no longer properly ordered toward the good, we suffer malice, which is the desire for what is evil because it seems to us good; because what is called the concupiscible appetite is no longer properly ordered toward “delectable” goods, we suffer concupiscence; and because what is called the irascible appetite is no longer properly ordered toward “arduous” goods, we suffer weakness. These consequences are called the “wounds” of sin. If reason is truly sovereign, then one might ask how it is possible for the appetites and emotions to be insubordinate to reason in the first place. The answer lies in how reason exercises its sovereignty. Borrowing an analogy from Aristotle, St. Thomas says reason commands the lower powers not by a “despotic sovereignty,” the way slaves are commanded by their master, but by a “royal and political sovereignty,” the way free men are ruled by their governor. Even though they are subject to his rule, they “have in some respects a will of their own,” so that they can resist his commands. Although the sin of our first parents did not take away our original nature and give us a different nature, a "sin nature," as some people mistakenly suppose, it is easy to see how this error arises. As we have said, original justice was a gift of grace to human nature, superadded to the principles that God built into it, and original sin is the deprivation of this gift. Although man has not literally lost his nature, the disharmony, dislocation, and disequilibrium that result from the deprivation of original justice are "like a second nature." Yet even so, St. Thomas comments, "sin cannot entirely take away from man the fact that he is a rational being, for then he would no longer be capable of sin. Wherefore it is not possible for this good of nature to be destroyed entirely.” The doctrine of original sin helps to understand a great many things about us that would otherwise be puzzling: For example, why is it so hard to do what we see that we ought to do, and avoid what we see we should avoid? It also reminds us of a fundamental difference between the way Christians reason about natural law, and the way pagans and secularists reason about it. Although the pagan can theorize about human nature and its laws, he is at a grave disadvantage in understanding them. Just because he does not know about original justice and original sin, he is apt to think that our disharmonious, dislocated, disequilibrated state is our normal state -- that original sin is our original condition. At the level of those deep intuitions that are expressed in myths of primal ruin, even he senses that something is wrong with us, that something is not as it should be. Yet at the level of theory, he does not know what to make of these intuitions. For though he may know all about the present human condition, he lacks the history of how its disorder came to be – and of how it can be remedied by grace. This concludes the series on natural law and original sin.Tomorrow: Attempt at a Definition (no, of something else)

|

Natural Law and Original Sin, Part 2 of 3Friday, 03-27-2015

Though sin dreadfully thwarts the fulfillment of the principles by which our nature operates, not even sin can obliterate them. Our nature, though wounded, persists. St. Thomas Aquinas explains with a pair of analogies. The first of these is the effect of clouds on glass. A transparent body has an inclination or readiness to receive light, from the very fact that it is transparent. Yet although this readiness always remains rooted in its nature, it is diminished by clouds which get in the way of the sun. In the same way, although we have a naturally inclination to virtue, sin diminishes it, not by destroying our nature, its root, but by impeding our nature from achieving its end. This can go on and on, because even if man goes on adding sin to sin, his nature, which is the root of the inclination to virtue, remains. Lest anyone misunderstand the first analogy and underestimate the seriousness of sin, St. Thomas’s second analogy is blindness. Even in a congenitally blind man, the potentiality for sight is still naturally present in the sense that he is an animal of a sort which is naturally endowed with sight. Yet this aptitude is not actualized or fulfilled in him, because something has prevented the proper formation of the eye. In the same day, the natural inclination to virtue persists even in the lost. If it didn’t, they would not suffer the remorse of conscience. However, the inclination to sin is not actualized in them because they have been deprived of grace by divine justice. The fact that not even sin can obliterate the inclination to adhere to God's law may seem comforting. It isn't, for what it really means that the wicked man is divided not only against God, but against himself. This division begins right now, in the present life. St. Thomas argues that because the wrongdoer disturbs three different orders -- his own reason, human law, and Divine law -- so he receives a threefold punishment, one inflicted by himself, one by man, and one by God. The one which he inflicts on himself, remorse of conscience, is united to the one which is inflicted by God, the withdrawal of His presence, because conscience is the interior testimony to God's law. Whenever a man acts against conscience, "he has by this very fact decided not to observe the law of God." Tomorrow: Part 3 |

Natural Law and Original Sin, Part 1 of 3Thursday, 03-26-2015

Since student letters day is Monday, why am I posting this letter on a Thursday? Because it’s not from a student. I thought it would be interesting anyway. Query: A colleague and I have been trying to think through the implications of our sinful nature. We say that the human race is “wounded,” “fallen,” “warped,” and so forth. Our vision is blurred. Our desires are out of whack. We are supposed to have brought this on ourselves. Anyway, is this situation of fallenness correctly described as a departure from our true nature as human beings? Or, at any rate, as a failure to develop fully as human beings? Perhaps you have written about this. The question is especially important in our own era because of the tragic, ongoing division with Protestants. Some historians claim that Protestant theology began to distance itself from natural law only in the nineteenth century. But the roots of this hostility go all the way back to the Reformers. They lie in suspicion of reason and nature as such, the former a temptress, the latter depraved beyond recognition. Martin Luther wrote, “As a young man must resist lust and an old man avarice, so reason is by nature a harmful whore. ‘But she shall not harm me, if only I resist her.’ Ah, but she is so comely and glittering.” To be sure, not even Luther denied the reality of the natural law; in fact he insisted on it strongly, a point which cannot be emphasized enough. The problem is that no such endorsement could continue to survive in the soil of such awful qualms. Calvin's theology is quite favorable to natural law. In various works, he finds a basis in natural law for the ordinance of marriage, the condemnation of fornication, the esteem due to the capable, the honor due to the old, the prohibition of incest, the help given to the needy, the affection of fathers for their children, the duties of sons toward their fathers (more generally of children toward their parents), and the even greater duties of husbands toward their wives. More fundamentally, he clearly understood something Luther failed to grasp -- that nature could not actually be bad. As he wrote, “it is not [to be] admitted that there is anything naturally bad throughout the universe; the depravity and wickedness whether of man or of the devil, and the sins thence resulting, being not from nature, but from the corruption of nature; nor, at first, did anything whatever exist that did not exhibit some manifestation of the divine wisdom and justice.” Rather than maintaining that human nature is bad, Calvin held that our good nature is in a bad condition, which is exactly correct. Nor -- unlike some of his followers -- did he hold that no good is left in us. What he held was that each good in us is injured. But the extremity of some of Calvin's language, and his denial of free will, did lead some of his would-be heirs to different conclusions, thinking that we have altogether lost our nature and received in its place something else, a “sin nature” -- an idea Calvin himself would have viewed as Manichaean. What then does it mean for nature to serve as a norm in the face of the Fall? Natural law thinkers do not suppose that nature is not fallen, but they seek to view the Fall in right perspective. We have not ceased to be human and become something else; we have not lost our nature and acquired a wicked nature, as though there could be such a thing as an evil nature; but our nature is disordered. Even though it preserves the same intelligibility, our vision of it is obscured and our power to follow it impaired. We are at odds with ourselves. As Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger once remarked in an interview, “creation has been damaged. Human existence is no longer what was produced at the hands of the Creator. It is burdened with another element that produces, besides the innate tendency toward God, the opposite tendency away from God. In this way man is torn between the original impulse of creation and his own historical inheritance.” These matters deserve more discussion than I can give in a single day, so I will return to them in the next two posts.

|

Nature, For and Against, Part 7 of 7Wednesday, 03-25-2015

Finally, the uneasiness of heterosexuals about their own conduct may manifest itself as a misplaced scruple against hypocrisy. They ask how we dare to disagree with anything said in favor of homosexual acts. After all, we don’t hear many complaints about heterosexual misbehavior, do we? That’s true, and there is only one possible reply: We ought to. We would not be so confused about homosexuality if we had not already allowed ourselves to become so confused about heterosexuality. The polarity of the sexes is the vaulted arch into two great natural goods: The generation of new life and the union of the procreative partners. Once these goods have been sullied by adultery, divorce, hooking up, cohabitation, abortion, pornography, and the contraceptive mentality, the celebration of same-sex attraction comes almost as a thing expected. Perhaps my readers will consider the analogy I am about to offer farfetched. But I think just as President Abraham Lincoln urged the North and South to join in binding the wounds they had inflicted together on their nation, so we should be urging those who suffer from same-sex attractions to join with those who do not suffer them to join in binding the wounds we have inflicted together on chastity. We dare not hold chastity in contempt; we dare not dispense with marriage; and we dare not tamper with its creational design. Too much good is at stake to treat these things lightly, too much power, beauty, and danger to waste it on selfish games. From the best gifts come the worst miseries, if we are too foolish to follow directions – the lessons built into our nature. This seven-part series, now concluded, has been adapted from my chapter in a book to be published by Ignatius Press.Tomorrow: Natural Law and Original Sin

|

Nature, For and Against, Part 6 of 7Tuesday, 03-24-2015

In my previous examples, the other person in the conversation was someone who experiences same-sex attraction. But most of our unconvinced friends will be heterosexual, and most of the difficulties of conversation with them about the topic arises either from the fact that so many are either leading sexually disordered lives themselves, or confusedly trying to defend friends and relatives who do. They may be reluctant to concede that any form of sexuality could be problematic, just because then they would be forced to face up to what is wrong with the other things they think they have to shield. One way the discomfort of heterosexuals about their own behavior manifests itself is misplaced fear of not being compassionate enough. They may exercise so little restraint in their own sexual lives that they consider it cruel to expect any restraint at all from anyone else. Perhaps it is sufficient to point out that though compassion is good, there is a difference between true compassion, which is a persevering commitment to the true good of others, and false compassion, which is a lazy disposition to approve of whatever they want. Another way heterosexual discomfort manifests itself is a misplaced desire not to discriminate. For example, people may say changing the laws of marriage “wouldn’t hurt anyone,” so why not make them “the same for everyone”? I answer this question with a question. Why are there marriage laws in the first place? After all, the law doesn’t take an interest in love in general; it ignores my relationship with my fishing buddy. But marriage is unique. It is the only institution that can give a child a fighting chance of being raised by a mom and a dad. To demand that the law regard two men or two women as married is to proclaim that henceforth family law should be based not on the well-being of children, but on the sexual convenience of grown-ups. Still think it wouldn’t hurt anyone? Tomorrow: Part 7. This seven-part series is adapted from my chapter in a book to be published by Ignatius Press.

|