The Underground Thomist

Blog

What the Twentieth Century Taught TotalitariansTuesday, 03-10-2015

The twentieth century taught some of us that totalitarianism is evil. What it taught some totalitarians is that their methods had to change. Do people resist the compulsory destruction of their cherished institutions? Very well, then compulsion must be made to look like liberty. What our local totalitarians call “nondiscrimination,” “choice,” and “neutrality” are devices by which the coerced substitution of one moral judgment for another is disguised as the suspension of moral judgment. The state pretends that it is not making judgments about sexuality, just prohibiting discrimination. But discrimination includes merely disapproving of sexual deviance. So the government schools teach children that anything goes, and then the campaign begins to prohibit private schools, religious schools, and the Church from teaching any other view of sexuality. Or the state pretends that it is not promoting abortion, euthanasia, and assisted suicide, just allowing people choice. But once these acts are legal, the state says they are a right, so that nurses must be coerced to assist in them, pharmacists must be coerced to dispense drugs that cause them, insurance carriers must be coerced to reimburse for them, and taxpayers must be coerced to pay for them. Or (this is coming) the state pretends that it is not against monogamy, just neutral among monogamy and other arrangements. But to revise the marriage laws so that these other arrangements are legal forces those who believe in monogamy into a polygamous legal framework, so that if a man takes a second wife, the first wife has no recourse but divorce. The smoothest camouflage for evil judgment is pretending not to judge. Our local totalitarians learned this a long time ago. The rest of us have been slow to catch on. Tomorrow: The Constitutional Meaning of Faith

|

What Is this NNL Whereof You Speak?Monday, 03-09-2015

Mondays are reserved for letters from students. This one is matriculating at Santa Clara University. Question: I was wondering if I could inquire more into the two types of natural law you talk about. I understand the concepts of natural law, but there's this other approach you mention -- the "basic goods" approach or NNL. How does that differ from a traditional approach to natural law as you see it? If you could let me know of any key differences, or point me in the direction of some reading material, I'd appreciate that a lot. Reply: There is only one kind of natural law (just as there is only one kind of gravity), but there is more than one theory of natural law (just as there is more than one theory of gravity). What I defend is the classical natural law tradition. The basic goods approach, which agrees with the conclusions of the classical tradition most but not all of the time, is also called the Grisez/Finnis theory, after Germain Grisez and John Finnis, and the new natural law theory, or NNL. Calling it “the new” theory is a little misleading, because the classical tradition, still alive and vigorously resurgent, is generating a lot of new work. But that’s how people speak. Since questions like yours come up so often, I included an appendix on the differences among the various theories of natural law in my books, The Line Through the Heart: Natural Law as Fact, Theory, and Sign of Contradiction. However, that appendix merely touches on the basic goods approach, so let me say a bit more. The main differences between the NNL and the classical tradition are as follows. (1) The NNL rejects natural teleology. For example, it refuses to reason about sexuality on the basis of the natural purposes and inbuilt meanings of the sexual powers -- on the basis of what they are for. This is such a huge departure from the classical tradition that many natural law thinkers would say the basic goods theory is no longer a “natural” law theory at all – there is no “nature” in it. I think that way of putting the matter is a bit overstated, since the NNL does rest on claims about one aspect of our nature, the deep structure of the practical intellect. (2) The NNL maintains what is called the incommensurability thesis – the proposition that none of the basic goods, the goods worth pursuing for their own sake, can be compared according to value. Here is one of the standard examples: Suppose you are playing golf, a child is drowning in the water hazard at the ninth hole, and you give up the game in order to rescue the child, press the water out of his lungs, and call an ambulance. Afterward, someone asks, “Why did you do that?” You reply, “Because life is more important than play.” The basic goods theorist would agree that you did the right thing, but say “That isn’t a valid reason.” (3) Instead of speaking of God as our greatest good, the NNL speaks of the “basic good of religion,” which means roughly having a connection with some source of meaning greater than oneself. Classical natural law theorists like me worry that this might mean anything. We also hold that there is no need to protect natural law theory from natural theology – from truths about God which are demonstrable by reason. (4) Finally, the NNL relies on a different analysis of the “object of intention,” of how to identify what an act is aiming at. For example, several years ago, a nun who was a member of the ethics board of a Catholic hospital in Phoenix was excommunicated for approving an abortion. At the time, her view was that the act was permissible because its object was not to kill the child but to save the woman’s life. However, the classical analysis holds that such an act is wrong, because its real object is to kill the child as a means of saving the woman’s life. In effect, the physicians were treating the child as the illness, not the illness, as the illness. Though NNL thinkers are generally pro-life, in this case they sided with the excommunicated nun (who subsequently conceded her error and reconciled with the Church). These are pretty big differences. Even so, most of the time classical natural lawyers and NNL thinkers are able to work on the same side of the fence, and consider themselves colleagues with disagreements. The situation does give rise to certain ironies. For instance, I have mentioned in previous posts that unlike some of my colleagues on the classical side of the table, I think Professor Finnis offers helpful insights about “one flesh unity” in the context of sexuality, and I have borrowed several of them, with modifications, in my own work. Even so, I am not altogether sure that he would be pleased by my doing so. The reason is that he makes these points in order to avoid natural teleology, whereas I find them helpful only in the light of natural teleology. Tomorrow: What the Twentieth Century Taught Totalitarians

|

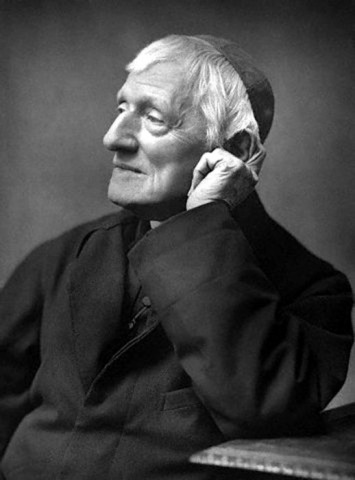

I Can Never Be Thrown AwaySunday, 03-08-2015

“God has created me to do Him some definite service; He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to another. I have my mission -- I never may know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. Somehow I am necessary for His purposes, as necessary in my place as an Archangel in his -- if indeed, I fail, He can raise another, as He could make the stones children of Abraham. Yet I have a part in this great work: I am a link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons. He has not created me for naught. I shall do good, I shall do His work; I shall be an angel of peace, a preacher of truth in my own place, while not intending it, if I do but keep His commandments and serve Him in my calling. “Therefore I will trust Him. Whatever, wherever I am, I can never be thrown away. If I am in sickness, my sickness may serve Him; if I am in perplexity, my perplexity may serve Him; if I am in sorrow, my sorrow may serve Him. My sickness, or perplexity, or sorrow may be necessary causes of some great end, which is quite beyond us. He does nothing in vain; He may prolong my life, He may shorten it; He knows what He is about. He may take my friends, He may throw me among strangers, He may make me feel desolate, make my spirits sink, hide the future from me -- still He knows what He is about.” -- John Henry Cardinal Newman, Meditations and Devotions

Tomorrow: What Is This NNL Whereof You Speak?

|

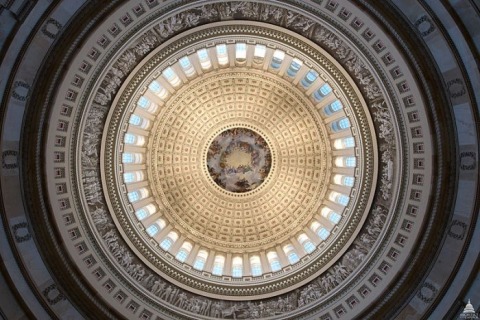

Are the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses Inconsistent?Saturday, 03-07-2015

The two First Amendment religion clauses are often described as though they were in conflict, so that they have to be “balanced” against each other. This is a manufactured problem. If you think that the purpose of the Free Exercise Clause is to encourage the practice of religion in every possible sense, but that the purpose of the Establishment Clause is to keep religion from being vigorous enough to influence politics, then of course you will think they are in conflict. But what do the two clauses actually say? The Free Exercise Clause does not say that the government should encourage the exercise of religion in every possible sense. What it says is that Congress must not prohibit it. That’s all. The Establishment clause does not say that the government should keep religion from influencing politics. What it says is that Congress must not make laws concerning official churches, like the Church of England. That’s all. There is no conflict whatsoever between saying that the national legislature must not prohibit the practice of faith, and saying that it must not make laws concerning official churches. Conflict arises only when you try to make the clauses mean more than they do. By the way: The chief reasons which were advanced for these clauses were themselves religious. The Framers didn’t want the practice of faith prohibited, because they thought we have duties to God. But they didn’t want Congress to get into the official church business, because they thought religious truth is best promoted by religious competition. The states, and the people thereof, were left to do as they thought best.

|

Still Small VoiceFriday, 03-06-2015

And behold, the Lord passed by, and a great and strong wind rent the mountains, and broke in pieces the rocks before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake; and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire a still small voice. And when Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave. And behold, there came a voice to him, and said, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” The story of Elijah’s experience at Mount Horeb after fleeing from Ahab and Jezebel gives rise to some of the strangest interpretations. Some people think that whatever the weakest voice is, that is the voice of God. I think the expression “still small voice” is a metonymy. The voice is not called still and small in the sense that it is weak, but in the sense that one can hear it only in interior silence. With the distractions of the wind, the earthquake, and the fire, Elijah found it difficult to find interior silence even in the desert. Besides all those, we have the iPod, the YouTube, and the all-consuming job. One wonders what we are trying to drown out.

|

Losing Our HeadsThursday, 03-05-2015

One of the aims of terrorists is to make their opponent lose their sense of balance and proportion. Judging from recent events, this isn’t difficult to do. Consider for example the terroristic murders at the Charlie Hebdo magazine. The liberty to criticize a religion one considers false must be defended, and satire is a legitimate genre of criticism. But satire doesn’t require obscenity. Without becoming indecent myself, I cannot even describe the acts depicted by some of the magazine’s cartoons. Now if the murders had never taken place, it would have been easy to say this. But since they have taken place, many opponents of terrorism now seem to think that if you don’t defend obscenity, you are soft on free speech and religious liberty. No. Pornographic cartoonists do not become heroes just by being killed. There is no moral equivalence. Indecency does not justify murder, which is infinitely worse. We really are at war with an implacable foe. But let us not lose our heads. That is just what the Enemy desires. Tomorrow: A Still Small Voice

|

Curious DifferencesWednesday, 03-04-2015

The other day I came across yet another claim by an atheistic philosopher that God is unnecessary to ethics, that we can ground moral duties even if there is no God. Let us set aside the question of whether this common claim is true. For purposes of discussion, let us proceed as though it were. Even so, it is curious that the theories of moral duty by atheists are usually much thinner than the ones developed by theists. From a theist point of view, some of the pieces are missing. Most of the atheists I know are consequentialists. In these cases, one of the missing pieces is the concept of intrinsically evil acts – wrongs that are wrong even if they happen to bring about good results. With only a few exceptions, even those who aren’t consequentialists tend to support abortion and euthanasia. So another common missing piece is the concept of the sacredness of human life. There are other differences, but let’s consider these. Leaving aside psychological motivations – of which I can think of several -- what logical reasons might there be for them? One, surely, is that if you don’t believe in God, then even if you do believe in goods and evils, you cannot believe, with the classical tradition, that human beings were made for something more than the goods of this life. One would think that this would make the goods of this life more important. Oddly, it doesn’t. It makes them less important. At least it makes life itself less important. A life in preparation for a greater life is infinitely more precious than a life that is all there is. A course of days that is already launched upon eternity is infinitely more momentous than an allotment of heartbeats that is already on the way to the abyss. A soul that is made in God’s image is infinitely more significant than the mechanisms that make a pathetic bag of organic chemicals think that it has a soul. Tomorrow: Losing Our Heads

|