The Underground Thomist

Blog

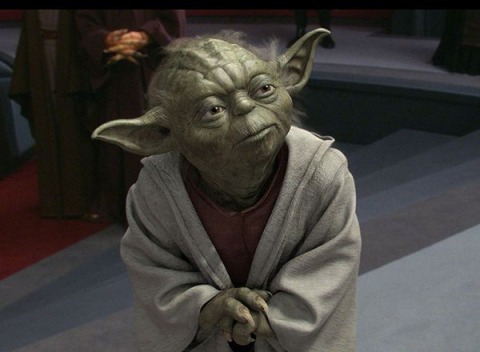

I Sense a Disturbance in the ForceMonday, 02-09-2015

Monday, as always, is for letters from students. You would think my letters would all be about things like natural law. Directly, no. Indirectly .... Question: I am 18 years old, a sophomore in college, and engaged to be married. My fiancé and I have agreed to get married one semester before I finish my bachelor's degree (one year, eight months from now) but I have a feeling we won't be able to wait that long. I know St. Paul’s saying “It is better to marry than to burn,” but we know that we are still not ready for marriage. We feel that by the time our wedding date comes around, we will be ready spiritually, emotionally, physically and financially. We both know it is not God's time yet, but we are very anxious to be together. We've already been together for one year 11 months, and we've been engaged for 10 months. We've prayed and we've fasted and we've asked for advice but every day that goes by seems to be more and more difficult to get through. I start to ask myself whether God really wants us to wait that long or if He rather us marry sooner so that we will not fall into temptation. How will we be sure when it is God's time? Do you have some advice for our situation? Reply: Thanks for writing. Now brace yourself, because I some questions for you. The first: If you're sure you aren't mature enough to marry, then what makes you think you're mature enough to get engaged? Turning it around: If you're sure that you’re mature enough to get engaged, then what makes you think you're not mature enough for marriage too? The second: The usual reason people have difficulty avoiding sexual intercourse is that they've already crossed too many other lines. If you want to avoid having sex, you have to re-cross those lines in the other direction — you have to go back. This means a real change in behavior: Avoid everything that arouses you. Yes, that includes drawn-out kissing sessions; you have to stop thinking of sexual arousal as recreation. The third: Being alone together is one of the most arousing things there is, so spend as little time as possible by yourselves (read that as zero). Instead, spend your couple-time with other people around; for example, restaurant yes, apartment no. If you back off from aloneness now, then it will be wonderful to be alone on your wedding night — but don't imagine that you can have bedroom privacy without the rest of the bedroom experience. Capiche? One more thing. I’ve been assuming that when you write “We've already been together for one year 11 months,” you mean you’ve been dating for that long. But if you mean you’ve been living together for that long, you are not being realistic. The situation is intrinsically unchaste. Praying for chastity while living together is like jumping off a cliff yet begging God not to let you fall. Living together yet trying to abstain from intercourse is like igniting the engines yet telling the rocket “Don’t blast off.” You aren’t made that way, my dear. Nobody is. If you’re serious about purity, live apart.

|

Whether All Roads Lead to RomeSunday, 02-08-2015

“There is a phrase of facile liberality uttered again and again at ethical societies and parliaments of religion: ‘The religions of the earth differ in rites and forms, but they are the same in what they teach.’ It is false; it is the opposite of the fact. The religions of the earth do not differ greatly in rites and forms; they do greatly differ in what they teach.” -- G.K. Chesterton, Othodoxy

|

Nero’s Indictment UpdatedSaturday, 02-07-2015

When Rome burned under Nero, the cry was "The Christians must have set the fires." This time it is our Rome that is burning. But this time the cry is, "The Christians are trying to drown us."

|

The Tower of BabelFriday, 02-06-2015

As in the days of Babylon on the plain of Shinar, men have begun to murmur among themselves, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves.” One version of the dream envisions adjusting people to their particular lots in life in order to “enhance” their performance and satisfaction. We could have soldiers who don’t need to sleep, file clerks who never get bored, laborers who never go on strike, miners who prefer the heat and dark, abortionists who don’t have bad dreams. In another, more egalitarian version, everyone is re-engineered the same way (except perhaps the engineers), so that life is more to our liking. Everyone could live forever, even if this meant putting an end to children, a point Europe has almost reached anyway. No one need ever become depressed, even if he had something he ought to be depressed about. No one need ever suffer pangs of conscience, no matter what he had done. No one need ever go mad from not knowing the meaning of his life, for our minds could be readjusted so we thought we knew already, or just didn’t need to know. I don’t think the Church is ready to answer the prophets of Shinar, whom I imagine arguing something like this: “You say freedom lies not in denying but in following our nature -- in humanizing ourselves, becoming more what God had in mind, fulfilling our inbuilt potentialities, our “immanent intelligibility.” Very well, we concede -- so it does! But what you call a human being is just a sophisticated mechanism; what you call its nature is its operating system; what you call its subjectivity or consciousness is its executive function; what you call its immanent intelligibility is the objectives built into its program; and what you call desires are their internal representations. Fulfilling our immanent intelligibility can therefore mean nothing more than becoming more successful in attaining what our programming leads us most strongly and persistently to desire. “What then is this longest, strongest desire? Preeminently, the increase of our power, or the power of our descendants, with whom we are programmed to identify. If so, then to act on this desire simply is to act freely, simply is to follow nature, simply is to humanize ourselves. Suppose the greatest step we could take to increase the power of our descendants were to make them something different than we are -- to free them from human limitations. “You might say that by taking such a step, we would not humanize ourselves but only abolish humanity. Say rather that in this case, the highest expression of our freedom is also its terminal expression -- that abolishing humanity is the most humanizing act we can perform. What parent would not sacrifice himself for his children? “You say that even if we expressed our own freedom by reinventing humanity, we would destroy the freedom of our descendants -- we would be turning them into artifacts, treating them as things. Perhaps you imagine them complaining that they didn’t ask to be transhuman! But I notice that you don’t level the same accusation against the Creator, for after all, we didn’t ask to be human. Well, our descendants haven’t asked to be human either. Why should we force them to be? “You say that created nature isn’t a limitation on our freedom, but the divine gift that makes freedom possible. So be it! Then we will be as gods to them -- dying gods, burdened with our sins -- and their reinvented nature will be the gift from us that makes their freedom possible. There are no two ways about it. If our freedom is following our nature, then their freedom is following theirs. To go with their new nature, they will simply have a new freedom. And wouldn’t it be a lot more fun?” Dialogue with transhumanists -- and make no mistake, there will have to be dialogue with transhumanists -- will require considerably more philosophical equipment than we presently possess, and will require it at several different levels. At the level of discursive reason, the metaphysics lesson must be prolonged. The differences between substances and mechanisms, between natures and programs, between the immanent intelligibility of our nature and what we strongly want, these things and others must be made more clear, clear to people who are not philosophers, or the dialogue will go nowhere. The whole ontology of modernity must be called into question, a stupendously formidable task. At the level of simple insight, the power of the mind by which it sees what it understands, the matters we are discoursing about must be brought closer to the eye, made accessible to intuition. One thing that needs to be seen before it can be understood is the sheer horror of the transhumanist ambition. The danger is not that proponents of this ideology could achieve what they desire, but that they might ruin humanity by trying. An even more important thing to be seen, or at least to be glimpsed, is divine transcendence. If we think that just because secular people are afraid of God, they must not long to see Him, we are mistaken. Under every disguise – and transhumanism is such a disguise -- that desire remains real and powerful, and must be offered the hope of satisfaction.

|

Lies, Damned Lies, and RelativismThursday, 02-05-2015

Statistics can so easily be manipulated to give misleading impressions that a famous little book is titled How to Lie With Statistics. The author wrote it in 1954. My economics professor assigned it in 1971. It’s still in print. Such cautions and warnings are all to the good. It’s as easy to sucker people with statistics today as it ever was. But many people, having learned that they can be fooled, refuse to accept any statistics whatsoever. They assume that all statistics are lies. Students diligently write down the numbers their teachers feed them, just in case they’re on the exam. But many go on believing what they want to believe. Perhaps this wouldn’t be so bad if what they wanted to believe were guided by common sense. But college in our day tends to be a destroyer of common sense, so all too often it’s coupled with epistemological relativism. If what’s true for you may be false for me, why then, a lie for you may be honest for me.

|

Anti-Realism and All ThatWednesday, 02-04-2015

Again, it is possible to fail in many ways, while to succeed is possible only in one way. – Aristotle. According to moral realists, like me, the sentence, “Murder is wrong,” means that murder, in fact, is wrong. Such sentences are capable of being either true or false; this one happens to be true. It describes the actual moral quality of murder, a property which belongs to the act irrespective of what any of us think, feel, or say about the matter. If I say “Murder is right,” murder is still wrong. In everyday speech we tend to use the term “relativism” as a catch-all for a variety of views which are actually somewhat different. What they have in common is that they reject moral realism. But they go off the rails for different reasons. The three most common kinds of moral anti-realism are relativism in the strict sense of the term, subjectivism, and non-cognitivism. To the relativist in the strict sense, the sentence “Murder is wrong” means that murder is wrong in relation to the speaker. Such sentences may be true for one person or group, he thinks, but false for another. Maybe murder isn’t wrong for, say, assassins. To the subjectivist, the sentence “Murder is wrong” may seem to tell us something about murder, but in fact it only tells us something about the speaker. One well known variety of subjectivism holds that what it tells us about the speaker is his feelings about murder – perhaps something like, “I dislike it, and I want you to dislike it too.” If the subjectivist says that such sentences are capable of being true or false – and he may not -- at best he means that they might be either correct or incorrect descriptions of the speaker’s emotions. “It’s all about you.” To the non-cognitivist, although the utterance “Murder is wrong” has the grammatical form of a sentence, it does not actually express a proposition at all. Consequently it is no more capable of being true or false than an utterance like “Whoops,” “blimey,” or “I’ll be dog-goned.”

|

HarmonizersTuesday, 02-03-2015

A recent newsletter of the American Maritain Association reminds us of the split personality of France, a country long noted for devotion to both Bastille Day and the feast day of Joan of Arc. The mid-century Thomist, Jacques Maritain, hoped that his country’s Christian aspirations might be harmonized with its avowed dedication to liberty. That was a tall order, because French faith had too often been united with the cause of reaction, and the notion of liberty with the cause of violent, anti-Christian revolution. Good point. Let us add that our country long enjoyed an advantage France did not have, because our founders were harmonizers from the beginning. Faith and reason, ancients and moderns, were all drawn into the struggle for self-government. Christian republicans and moderate admirers of the Enlightenment made common cause. For a while it seemed to work. But there was no real synthesis, only a colloidal suspension. Eventually the elements settled out, like milk and cream. Although from its first centuries the Church has united faith and reason, the young republic’s most influential religious movements tended to hold intellect in suspicion. Although American proponents of natural rights were the beneficiaries of a rich and ancient tradition, they were ungrateful ones, adopting “made simple” versions of natural law theory that ultimately came to seem unbelievable. Now, having thrown away faith, those who formerly styled themselves defenders of reason can no longer bring themselves to believe in reason either. Abandoning God, they have even lost man. So the European crisis of culture is our crisis too. “American exceptionalism” means simply that here it has taken longer to come to a head. Could there have been a real cultural synthesis? Yes -- and there still could be, for faith and reason really are allies, and our past mistakes are not an irresistible fate. But can it be achieved in the way we have previously gone about it? That road is closed.

|