The Underground Thomist

Blog

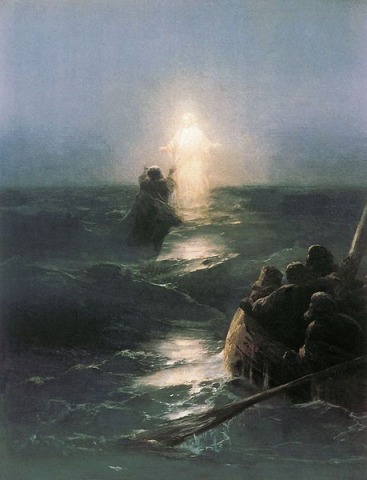

MiraclesSunday, 01-04-2015

"Somehow or other an extraordinary idea has arisen that the disbelievers in miracles consider them coldly and fairly, while believers in miracles accept them only in connection with some dogma. The fact is quite the other way. The believers in miracles accept them (rightly or wrongly) because they have evidence for them. The disbelievers in miracles deny them (rightly or wrongly) because they have a doctrine against them." -- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

|

Is Modesty the Cause of Lust?Saturday, 01-03-2015

I suppose we have all heard the argument that that modesty produces dirty minds by promoting a “mystique” about the body. On this view, if we want clean minds, we should show more rump and cleavage. There is a grain of truth in the argument, because clothing – especially teasing clothing – surely can provoke fantasies about what lies underneath. Just like speed limits arouse some people to speed. But the argument misses the most important thing. The body really is a mystery. It is the visible means by which the invisible soul makes itself known to other souls. To “demystify” it is to falsify it -- to present it as something other than it is. Practices like mixed-sex nude swimming, which the fans of demystification adore, make the body’s interesting ways seem merely gross and dull. This beautiful, perishing thing comes to seem just a lumpish corpse, a somewhat ugly tool of flesh, less than even a hammer or pocket knife, good for nothing for placating the occasional, meaningless desire.

|

My Favorite AtheistFriday, 01-02-2015My favorite atheist is Guenter Lewy. I have never looked into his beliefs about ethics in general; it’s not that. What interests me about him is his confession, in a little book he wrote some years ago called Why America Needs Religion, that he envies his religious friends their moral resources. Lacking the model of the love of God, he says, many people on his side love “humanity,” but far fewer love “individual human beings with all their failings and shortcomings.” They may do good works, but they are “not likely to produce a Dorothy Day or a Mother Teresa.” Though Lewy insists that a few individuals manage to be good without believing in God, he doesn’t think a whole culture can do so. This is where it gets interesting – because why doesn’t he? The reason most atheists give is that common people are not intelligent enough to grasp the true, godless reasons for being good. Lewy’s reason is different. It turns out that in his view, even these few who can be good without believing in God are living on borrowed scruples. For although nonbelievers can recognize such truths as the sanctity of life (so that in that sense these truths are self-evident), they are unlikely to discover them (so that in that sense they are not self-evident at all). Yet somehow -- mysteriously -- believers can discover them. The upshot would seem to be that humanism depends for its very life on religious traditions that it can neither produce nor support. Secular humanism is the parasitic variant that harms its religious host; what Lewy calls nontheistic humanism is at best the commensalistic variant that tries to do no harm. Now if only the gentleman had followed his premises just a little bit further.

|

Evolutionary Ethics, Part 2 of 2Thursday, 01-01-2015

One of the curious things about the proponents of so called evolutionary ethics is that although they wave the banner of science, their ethics are actually arbitrary. Take for example Robert Wright, who proposes utilitarianism. Since you can’t derive utilitarianism just from belief in natural selection, how does he get there? He argues like this: 1. Since Darwinism destroys traditional belief, once it gets loose in the world it becomes harder and harder to find principles on which everyone will agree. 2. In such a world, which “for all we know is godless,” minimalism rules; fewer principles are better than more. 3. Under minimalist rules of play, utilitarianism wins, because it has only one principle: Pleasure good, pain bad. 4. Although this does not prove the goodness of pleasure and the badness of pain, we do in fact regard pleasure as good and pain as bad. “Who could disagree with that?” Wright asks. The argument is full of holes. One of them is that even if we do have to play by minimalist rules, the kind of minimalism that is likely to strike people as plausible depends on what kind of people they are. In cynical times, when they are well-fed, the One Plausible Principle may seem to be “Pleasure is good.” But in violent times, when they are afraid, the One Plausible Principle may seem to be “Death is bad.” That was the principle propounded by Thomas Hobbes in 1641. Need it be pointed out that the premises “Pleasure is good” and “Death is bad” entail very different courses of action? Another problem is that Wright confuses happiness with pleasure. People might agree with him that happiness is good, yet not agree with him that happiness and pleasure are the same thing. In fact, for many reasons, most of the Western tradition has denied it. For instance, happiness abides. Pleasure doesn’t. Or they may agree with him that pleasure is good, yet deny that it should be pursued as a goal. For another of those annoying insights of the Western tradition is that single-minded pursuit of pleasure dries up the springs of pleasure. People most readily experience pleasure as a result of pursuing goods other than pleasure. Or they may agree with him that pleasure should be pursued as a goal, yet not agree with him that aggregate pleasure should be pursued as a goal, as utilitarianism requires. If torturing one innocent soul would make everyone else much happier, then pursuit of the greatest possible aggregate pleasure would require torturing him. In fact it would require torturing him no matter why that made everyone else so much happier -- even if there were no other reason than that they were all sadists. Apparently Wright has not thought things through this far. You would think that before throwing out the Western ethical tradition, evolutionary ethicists would try to learn something about it. Apparently not.

|

Evolutionary Ethics, Part 1 of 2Wednesday, 12-31-2014

One of the hottest fads in social science is “evolutionary psychology,” also known as “evolutionary ethics.” The story line is that by considering how we came to be, we will learn more about how we are. According to this view, Darwinism reveals the universal, persistent features of human nature. Why it should do so is very strange, because Darwinism is not a predictive theory. For instance, it does not proceed by saying, “According to our models, we should expect human males to be more interested in sexual variety than human females; let’s find out whether this is true.” Rather, it proceeds by saying, “Human males seem to be more interested in sexual variety than human females; let’s cook up some scenarios about how this might have come to pass.” In other words, the theory discovers nothing. It depends entirely on what we know (or think we know) already, and proceeds from there to a purely conjectural evolutionary history. These conjectures are made to order. You can “explain” fidelity, and you can “explain” infidelity. You can “explain” monogamy, and you can “explain” polygamy. Best of all (for those who devise them), none of your explanations can be disconfirmed, because all of the data about what actually happened are lost in the mists of prehistory. In the truest sense of the word, they are myths -- but with one difference, which is this: The dominant myths of most cultures encourage adherence to cultural norms. By contrast, the myths of evolutionary ethicists encourage cynicism about them.

|

Arcade’s DeceptionTuesday, 12-30-2014

“‘Moreover,’ added Arcade, ‘I freely acknowledge that it is almost impossible systematically to constitute a natural moral law. Nature has no principles. She furnishes us with no reason to believe that human life is to be respected. Nature, in her indifference, makes no distinction between good and evil.’” -- Anatole France, The Revolt of the Angels There are two things to understand about this view: (1) why it seems so obviously true to contemporary man, and (2) why it is false. The problem is that several centuries ago, we tore out the teleological guts from our conception of nature. If you no longer recognize pattern and significance in what happens, then “nature” can mean nothing to you except that stuff happens. Since some of the stuff that happens is bad stuff, you inevitably conclude that nature is indifferent to good and evil. It is a perfect example of how mistaken ideas enjoy a double life. First we assume them; then we forget that we have assumed them; finally we dig them up again and shout “See what I’ve discovered!” Can we stuff the teleological guts back in? Sure. To vary the metaphor, all we have to do is stop turning our eyes away from what nature is actually like. What would we notice if we did? One thing we would notice that nature is full of developmental arrows: Go This Way. Acorns turn into oaks; oaks produce acorns but they do not turn into them. Babies turn into adults; adults do not run backwards and finally re-enter the womb. The point isn’t that nothing ever interferes with the course of development, for some children do fail to thrive, and some adults lose their capacities. Rather the point is that there is a course of development. For natural potentialities to unfold is naturally good; for them to be thwarted is naturally bad. Another thing we would notice is that nature is full of purposes. Purposes exist in one way in the mind, in another way in things, and in yet another way in the mind of God. Let us consider how they exist in things. We don’t have to read God’s mind to know that hearts are for circulating blood; but if that is so, then a good heart is one that pumps well, a bad one is one that pumps badly, and we ought to help bad hearts pump better. So nature is not indifferent to good and bad that way either. Still another is that for beings like us, these purposes are coupled with meanings. Whenever I give myself sexually, I am doing something that cannot help but mean the possibility of new life. Someone might object "That's not true. The chance of new life isn't a meaning of sex, at least not for me, because I don't want it. I even take steps to prevent it." I'm sorry, but what you intend subjectively can't change what your act means objectively. To join in one flesh is to say, "I give myself to you in all that this act means," even if my mouth shapes the words, "It means nothing." And have you noticed Arcade’s chief trick – that he does not consider the moral intellect natural? But man is a rational being, and the first principles of practical reason are inscribed upon the tablets of his heart. If it were not natural for us to reason morally – then how could it even occur to us to criticize nature for not being moral enough?

|

Is History All in Our Heads?Monday, 12-29-2014

Readers: Thanks to those of you who responded to my question last week about whether it would be helpful to reserve Mondays for lightly edited letters from undergraduate and graduate students. I’ve decided to do so. This young woman wrote to my alter ego Theophilus at the height of the Da Vinci Code craziness, but the problem she describes is still very much alive. Actual Query: I'm a senior at a secular state university, and as I've advanced in my coursework, I've come to know my fellow students more closely. I have learned how to defend my Christian faith on many points, but one point continues to stump me. Most of my fellow students accept without a shadow of a doubt the saying "history is nothing more than a lie agreed upon." They think that no accurate historical account has ever existed or could ever exist, because history is "only written by the winners." In their view, the only history that matters is each person's subjective experiences. This view stymies me any time I try to discuss things like the events of Jesus' life. How can I logically and reasonably defend the fact that some history can be known with confidence? How can I make Christian scripture seem relevant to those who see all historical documents as biased texts written by "the winners"? Reply: Your problem with your classmates is ridiculously easy in one way, but terribly difficult in another. Let's take the easy way first. Their proposition is that no historical claim has ever been accurate, and that no historical claim can ever be made with reasonable confidence. But wait! To say something about what has or hasn't "ever been" is to make a historical claim. So their own claim is historical too! Now if it's true that no historical claim has ever been accurate, then their claim that no historical claim has ever been accurate is inaccurate too. But in that case some historical claims may be accurate, which means that their view is wrong. Their opinion is self-refuting. Here's another way to refute it. Their reason for thinking that no historical account can ever be trusted is that "history is written by the winners," and winners can never be trusted. But if it's true that the majority of the students at your school accept this view, then for the time being, they are the winners there. Their own premises prove that they can't be trusted. Who's left? Well, people like you, who say that reasonable confidence can be placed in some historical claims. Still another way to demonstrate the absurdity of their position is to show that they don't believe it themselves. If they did, they would never place confidence in any historical account whatsoever. But they do. How do we know that? Because, as you said, they do place confidence in their own subjective accounts of the things that have happened. According to them, no other histories "matter," but these histories do. This is a good time to ask them what that means. When they say that their subjective histories "matter," do they mean that these histories can be reasonably accepted as true? If they answer "No," then they're claiming that it's reasonable to act on premises that it isn't reasonable to believe. That doesn't make sense. But if they answer "Yes," then they are admitting that we can place reasonable confidence in some historical claims after all. The final way to undercut their position is more constructive. A lot of history really is unreliable, and we might as well admit it. But how did we find out that it was unreliable? We found out by examining the historical evidence. But if that's what we did, then not all historical reasoning is worthless after all. One has to proceed with caution, of course, scrutinizing the evidence and keeping a lookout for distortions, but that's not the same as utter skepticism. The moral of the story isn't that history is impossible, but that history is difficult. That shouldn't surprise us, because everything worthwhile is difficult. Patience is difficult, love is difficult, plumbing is difficult -- they all require sweat. The same goes for talking with your classmates. The arguments I've offered may seem pretty obvious, but as I said at the beginning, your problem is easy in one way, but fiendishly hard in another. Since the view that reality can't be known refutes itself, no one can swallow it just by making a mistake; anyone sharp enough to understand it is sharp enough to see through it too. But this implies that anyone who does swallow it must very badly want to swallow it. Now ask yourself: What sort of motive could be strong enough to make someone want to shut out the claims of reality? I know of only two: Suffering so extreme that it produces insanity, and sin so impenitent that it produces insane ideologies. You're not just dealing with an intellectual problem, my dear. You're dealing with a spiritual one. So reason, reason, reason with your friends -- but pray, pray, pray for them as well. One last thing. (Why am I always saying "one last thing"?) I'm glad that you want to evangelize, but I hope that isn't your only reason for defending the knowability of the past. All truth belongs to God; it's worth knowing for that reason alone. Professor Theophilus

|