The Underground Thomist

Blog

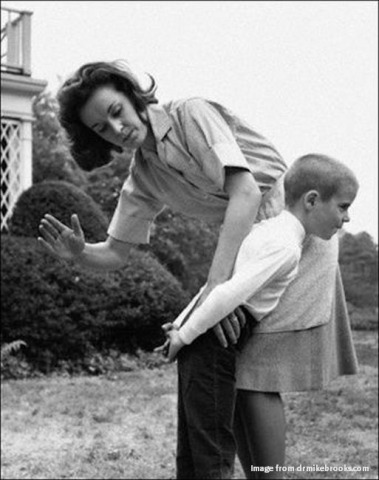

Spanking -- A Grain of SaltMonday, 04-15-2024

Query:I have been brought up under the impression that the Bible not only permits, but even glorifies spanking of naughty children. It is implied that the punishment is an act of love, as it will be good for the child. It is even said that one who does not spank, hates his child. Certainly this is the prima facie teaching of the book of Proverbs: “He who spares the rod hates his son, but he who loves him is diligent to discipline him.” “Discipline your son while there is hope; do not set your heart on his destruction.” “The rod and reproof give wisdom, but a child left to himself brings shame to his mother.” The letter to the Hebrews seems to go even further by teaching how God disciplines us in an analogous way as our earthly fathers have, with the same goal of harvesting righteousness through painful punishment: “And have you forgotten the exhortation which addresses you as sons? – My son, do not regard lightly the discipline of the Lord, nor lose courage when you are punished by him. For the Lord disciplines him whom he loves, and chastises every son whom he receives. It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons; for what son is there whom his father does not discipline? ... For the moment all discipline seems painful rather than pleasant; later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.” This makes it seem like parents spanking their children would be actually following the example of the perfect love of God. However, this teaching seems to be in direct contradiction with the recent findings of social science. Could you comment on the scientific validity of such studies? If the science is right, then is the Scriptural teaching mistaken? Or have I misunderstood it? If so, why is it so easy to get it wrong?

Reply:I take the texts you mention to mean, broadly, that parents who do not discipline their children are asking for trouble later on. From the fact that some of the texts refer to specific forms of discipline, I don’t understand the texts as requiring the employment of just these modes of discipline. In a culture in which, say, a switch is the most common way to punish disobedient children, it would be natural to refer to discipline in general by the phrase “the switch.” We speak that way even in contexts in which it is obvious that we do not intend to be taken literally; for example, we may say that a worker was “taken to the woodshed” by his supervisor, even though no workers are literally taken to any woodsheds. So, if I am reading the texts correctly, it would not be a violation of biblical teaching for a parent to forgo corporal punishment if another form of punishment turned out to work better with his child. The point is that discipline is neglected only to the child's peril. As to the empirical question -- how well does corporal punishment work? -- I don’t know, but I would hesitate to leap to broad conclusions from recent research when I don’t know whether they controlled for cultural expectations, or even what they meant by corporal punishment. Beating up children is obviously wrong. Giving a child’s butt a whap or two with a paddle – as was done with miscreants in my high school – is a very different thing. My own experience makes me a bit suspicious, just because different children respond differently to the same punishments. Some children do respond badly to spanking. Some don’t. There are some surprises with older people too. It would never happen today – but I know a man, a retired city planner, who blesses the day one of his college ROTC instructors grabbed him, took him over his knee -- and swatted his behind for not taking his studies seriously! To be a young adult, and yet be treated like a spoiled child, shocked him out of a deepening pattern of slack and irresponsible behavior. I would never do that to a student, nor would I ever recommend doing it. (Hear that, O my administrators?) I wouldn’t have reacted as he did either. But he swears that it changed his life. Interesting. And as to resentment, do you know what? My own students sometimes resent me just for giving them grades less than B for their essays. Yet I haven’t found that it works better to give them all As.

|

EsotericismMonday, 04-08-2024

For members of a certain esotericist school of thought, Exhibit One is Plato’s Republic. They take to an extreme the commonplace observation that Plato makes his character Socrates speak ironically. According to them, the Republic hides Plato’s disturbing real teaching behind a comforting, conventional teaching that does not even come close to representing what he actually believes. We are told that all the great philosophers wrote in this way. But a disturbing esoteric teaching hidden behind a comforting surface teaching is the opposite of what we actually find. Socrates puts his most radical proposals front and center: Community of property, community of wives, “noble” lies, and the same way of life for men and women. What the esotericists consider his hidden teaching -- that since a perfect regime is impossible, we ought to practice moderation – is not subversive. So what esotericists say publicly contains a contradiction. If I reasoned about them as they reason about great thinkers – which I think is how they would like to be viewed – then I would regard the contradiction as a deliberately planted clue that it is they, not the ancients, who write esoterically. The reassuring, conventional counsel of moderation is just a cover story, and their real view is radical and disturbing. But of course that couldn’t be true, could it? Related:LabyrinthSo-Called Self-Ownership

|

A Few DropsSunday, 03-31-2024

Many indeed are the miracles of that time: God crucified; the sun darkened and again rekindled; for it was fitting that the creatures should suffer with their Creator; the veil rent; the Blood and Water shed from His Side; the one as from a man, the other as above man; the rocks rent for the Rock's sake; the dead raised for a pledge of the final Resurrection of all men; the Signs at the Sepulchre and after the Sepulchre, which none can worthily celebrate; and yet none of these equal to the Miracle of my salvation. A few drops of Blood recreate the whole world, and become to all men what rennet is to milk, drawing us together and compressing us into unity. -- Gregory Nazianzen, Oration 45 (the Second Oration on Easter)

|

Is Dropping a Friend a Sin?Monday, 03-25-2024

This letter was from a high school student – and this is fourth (and last, for now) in a short series of reruns of old columns which I wrote many years ago, as the fictional Professor Theophilus, in an online magazine for Christian college students. Several people have been kind enough to say that my Ask Theophilus columns kept them sane in those days.

Question:I have two girl friends whom I met only a week ago. They claim to be Christian, and I believe them -- I know for a fact that they attend and are active at church. My problem lies in the fact that they do not behave or talk in godly ways. I am often left feeling very uncomfortable around them because their behavior is at odds with mine. They know I see things differently, and they know what they do bothers me, but I try my best to be polite and kind. Would I be a snob to discontinue my friendship with them because of how I feel about their behavior? Should I even consider not being their friend?

Reply:It's all right to drop one-week acquaintances who make you uncomfortable. If they had been long-time friends, some explanation might be necessary, but that's not the case. You don't have to make an announcement; you just avoid seeing them socially. Of course, we all struggle with temptation to sin, so it would certainly be hypocritical if we insisted on associating only with perfect people. However, that doesn't mean that you have to put up with anything from anybody. There is no obligation to continue in that special relationship called "friends." Breaking up confuses a lot of young Christians, because Christian social life is based on love -- and isn't love supposed to be forever? It all depends on which kind of love you mean. Some loves are forever: God's love for His people, the love of His people for Him, and their brotherly love for each other. Other loves are at least lifelong: Kinship, marriage and a few other relationships, usually based on vows. But most bonds aren't like that. Business partners, whose relationship is based on profit, don't have to do business until death. Roommates, whose relationship is based on convenience, don't have to share rent until death. What is your relationship with the two girls? I'd call it being pals -- the kind of friendship based on mutual liking. But it isn't a sin to stop liking. One thing to remember: Even if you do stop having friend-love for someone, you have to go on having neighbor-love. You have to continue being honest, fair and kind to him; you have to continue desiring good for him and you have to keep from seeking revenge or spreading gossip. Even if he acts like a rat! By divine standards, we're often pretty ratty. That's why we need God's mercy.

|

The Fog of, Um, WarMonday, 03-18-2024

This is the third in a short series of reruns of old columns which I wrote many years ago, as the fictional Professor Theophilus, in an online magazine for Christian college students. Several people have been kind enough to say that my Ask Theophilus columns kept them sane in those days.

Query:My girlfriend and I have been dating for almost a year. Although we're not yet engaged, we're not just dating for the heck of it -- I think the relationship is marriage-bound. We're both Christians, and both committed to remaining virgins until marriage. The problem is that we've become more and more physically intimate. I'd call the present level “heavy making out.” This crosses serious ethical and spiritual lines for both of us. We know we’ve messed up and can't continue in this behavior. The question is, what do we do next? Break up? Not touch at all? Or what?

Reply:It's nice to have an easy question for a change! No, you don't have to break up, and you don't have to avoid touching at all. But you do need to know what to avoid, and you do need to know how to be successful in avoiding it. You may think you already know what to avoid -- after all, you've just told me that you didn't avoid it. But let's review anyway. What to avoid? Avoid intercourse (of course), avoid whatever resembles intercourse (for example oral sex), and -- this is the important one to remember -- avoid whatever gets your motor running for intercourse. The God-given purpose of sexual arousal is to prepare the two spouses for intercourse, and it achieves that purpose so well that once arousal happens, intercourse tends to follow. Holding hands with your girlfriend while walking across campus probably doesn't put you in that condition, but other things do, and they are the things to avoid. I know that you know what they are, because, of course, that's why you do them -- arousal is enjoyable. The problem is that arousal can't be “used” as recreation. You can't turn on the rocket motors and then tell the rocket not to lift off. Besides, that behavior just isn't pure; arousal should be saved for your wife. Why? For the same reason that intercourse should be. And your girlfriend isn't your wife yet. How to be successful in avoiding it? Don't wait until you're aroused to ask yourself “Am I becoming aroused?” Why not? Because you'll be tempted to give yourself a dishonest answer. Instead, make a list of things not to do so that your decision is already made ahead of time -- then just don't do them. Does something get your motor running? Put it on the list. Is something difficult to stop doing? That's really the same question asked a different way. Put it on the list too. Whatever she thinks gets your motor running and whatever she thinks you find it hard to stop -- don't argue; write those things too. And of course she follows the same steps, putting herself in your place and you in her place. Second, don't trust that will power alone will be enough to keep you on the right side of the line. We aren't made that way. Just as the purpose of arousal is to prepare the two spouses for intercourse, so the purpose of being alone together is to prepare the two spouses for arousal. Logically, what follows? You should simply avoid being alone together! Of course I don't mean you can't ride in an elevator together, but you shouldn't be all by yourselves for extended periods of time. Here are some examples. Have dates in public places, like restaurants, not in secluded places like her apartment or that lonely spot in the park. If you want to watch a DVD together at your girlfriend's place, okay, but invite a couple of other friends over to watch it with you. When they leave, you leave -- and at the same time. See where I'm going? I think you'll find that following this advice puts your whole relationship on a different plane. It makes it possible to find out how you really feel about each other without the fog of arousal -- which is every bit as confusing as the fog of war.

Afterword:The author of the letter wrote back to thank me for the advice and say “You've probably saved my girlfriend and me from an imminent breakup.” Isn't that interesting? People are always imagining that sex preserves non-marital relationships. Actually, sex confuses them. Purity preserves them.

|

I Don't Like It HereMonday, 03-11-2024

This is the second in a short series of reruns of old columns which I wrote many years ago, as the fictional Professor Theophilus, in an online magazine for Christian college students. Several people have been kind enough to say that my Ask Theophilus columns kept them sane in those days.

Query:I'm a freshman in college at a university run by [a certain Christian denomination], but I really don't like it. The longer I'm here, the more I feel like I'm getting theology shoved down my throat. I'm not really in college with any particular goals in mind: I'm kind of just here because I'm not sure what else to do. So does it make sense to leave? I think the college experience has benefited me, but I find myself becoming more and more resentful of the “Christian” part of it. I have to take many more ministry-theology classes as a part of my general requirements, and I'm really not interested. I really need advice: I don't want to make a decision I'm going to regret, especially considering the investment.

Reply:The question you need to ask yourself is why you resent “the Christian part of it.” No, I'm not scolding you. Your reasons for resenting the theology requirements may be either good or bad, but you have to find out what they are. Here are some of the possibilities: 1. The real problem is although you recognize the value of college, you're just not ready for college right now, and the theology requirements are an easy target for your resentment about everything in general. 2. The real problem is that you prefer a shallow faith, and you resent the theology courses because they urge you to cast your net in deeper waters. 3. The real problem is that although you do want a deeper faith, you resent the theology courses for pushing you faster than you can go. 4. The real problem is that something is wrong with the theology taught in those courses. It doesn't answer your questions, or it answers them poorly, or it just doesn't have the aroma of Christ. 5. The real problem is that your theology courses are designed for people who are going into church-related professions, and that's just not your calling. Don't answer quickly. Take all the time that you need. Think; ponder; pray. You need to be sure of your answer. If the answer is number 1, drop out of college for awhile. Get a job, work hard, be responsible, save money. If you live at home, pay room and board. After a few years, think about college again. You may feel different than you do now. If the answer is number 2, try to understand why you don't want to cast your net in deeper waters. That's like preferring less life to more life. Perhaps there is a professor or counselor at the college you could talk to about this. If the answer is number 3, I suggest that you change schools -- not to one that doesn't push you spiritually (because we all need that kind of push), but to one that pushes at a pace you can keep up with. If the answer is number 4, you should probably consider not just a different school, but a school that teaches a different theology. Notice that I said “consider”; I'm not telling you to do it. By all means hold onto Christ, but seek a place where you can find all of His truth. If the answer is number 5, look for a university where the theology requirements are geared to people more like you -- people who are serious about their faith, but not called to professions in the church. Probably, possibly, if! I hope you weren't looking for a simple answer, because I haven't given you one. But maybe I've steered you to the right questions.

|

Does It Ever Get Better?Monday, 03-04-2024

This is first in a short series of reruns of old columns which I wrote many years ago, as the fictional Professor Theophilus, in an online magazine for Christian college students. Several people have been kind enough to say that my Ask Theophilus columns kept them sane in those days. Query:I'm pursuing a Ph.D. in English literature at a secular research university. For the most part my professors and colleagues are very open to my academic discussions of faith. I've found a local community of believers and joined a weeknight discussion group organized by the church. I really enjoy interacting with both Christians and nonbelievers in an academic setting. I like my field in itself, I enjoy teaching, and I've had the joy of seeing many of my friends become Christians as they interacted with thoughtful believers trying to be faithful in the academy. All the same, I think about quitting the field weekly, maybe daily. Everyone in my program who takes work seriously at all seems to be neglecting friends and family and sleeping 5-6 hours a night, just to get by. The sheer amount of work the program expects of students is incredible. I'd like to have more time to be involved in my church, do volunteer work, and maybe even cook a meal and enjoy it with friends. Though I'm fighting, I can also feel the burden of work stifling my relationship with God. It's really hard to do more than skim through a Psalm in the morning and then start work. Though I take Sundays off, it's hard to sustain whatever thinking I do about God throughout the week. I guess what I'm asking is: Does it ever get better? Will I ever have more time? Or is the graduate school lifestyle the same one I can expect in my academic career?

Reply:Of course it's possible that you shouldn't be in graduate school, but you don't give much reason for thinking that this is the case. To start with: Yes, it gets better. Frankly, though, it doesn't sound too bad for you now. You obviously find time for worship and other church activities several times a week. You obviously have time for friends, or you couldn't have had the joy of seeing “many” of them turn to Christ. You just want more of these good things. I can hardly blame you, but we can't have everything at once. What about losing sleep? Five hours is a little stiff, but six hours a night, at your age, for a few years, doesn't sound so bad to me. People who are in at the start of something new and big often lose sleep. Newlyweds do. New parents do. People beginning new careers or businesses do. People organizing volunteer ministries do. People in love do. Converts do. Should we be surprised that grad students do too? I said a few moments ago that it gets better. Let me fine-tune that statement. It can get better, but that depends largely on you. Perhaps these two reflections will help you. First, about grad school itself. Needless to say, it isn't easy, but even so, many grad students work harder and lose more sleep than they need to. Ironically, the commonest reason is that they are so smart. All through high school and college, they were the ones who breezed by while others had to toil. Grad school is often the first time in their lives that they've really had to work the way other students have had to. Suddenly they're forced to learn the time management habits that everyone else learned years earlier. Put all this together with the fact that for the first time in their lives, everyone around them is just as smart as they are, and what do you get? A recipe for insecurity, an urge to overwork, and a motive not to take the time to learn the habits that would make it all easier -- they take too much time to learn. You keep telling yourself that you don't have time to sleep because you have so much to do. But the less you sleep, the slower you work, and the more the work piles up, the less you sleep. Naturally, you get sick. The prospect of losing time to illness terrifies you, so you refuse to take time out to rest. Because you do refuse, the illness lasts for weeks instead of days, and you lose more time still. May I point out the obvious? None of this is necessary. It's driven by anxiety, not need. Second, about spiritual discipline. The sanctification of everyday life is difficult; everyone finds it hard to sustain a focus on God throughout the week, not just grad students. Having too much work makes it hard -- how right you are! But believe me, not having enough work would make it harder still. I commend you for wanting more quiet time to pray, but you already have far more than you think. You can pray while you're walking to school; you can pray while you're riding the bus; you can pray while you're making your dinner. True, you won't always be able to pray in words -- you'd find it hard to do that while talking with your thesis supervisor -- but you can have a prayerful spirit even then. When St. Paul writes “Pray without ceasing,” I don't think he's talking about having a longer quiet time, though that's good too. I think he's talking about the cultivation of an interior quietness of soul that makes it possible to pray literally all the time. May I once again point out the obvious? Progress in interior quietness will also help you in time management, because the place that anxiety once filled is more and more filled up by God. As I said before, perhaps you shouldn't be in graduate school -- perhaps you aren't as well suited to the academic life as you seem to be -- but I don't think so. I think your problems can be fixed. Yes, it gets better, even when it gets harder, as sometimes it will. That's how the path goes. I don't mean the path of scholars, though scholars should follow it too. I mean the path of God.

|