The Underground Thomist

Blog

David, Goliath, and SubsidiarityMonday, 02-26-2024

The usual reason offered for subsidiarity – but I am getting ahead of myself. What is subsidiarity? And why should you care? Let me distinguish between the subsidiarist worldview and the subsidiarist rule. The worldview of subsidiarity is that the society as a whole is not just a mass of individuals, nor is it a unitary sort of thing, but it is a partnership among many smaller partnerships in a good life – an alliance among forms of association such as families, friendships, churches, neighborhoods, business firms, craft unions, clubs, and so on. The rule of subsidiarity is that “it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do.” This wording goes back to an encyclical of Pope Pius XI in 1931. However, a very similar idea is found in Protestant social thought, where it is more often called “sphere sovereignty” -- and it is generally viewed not just as a “religious thing” but as an outgrowth of the classical natural law tradition. On the negative side, subsidiarity implies that the forms of association which are greater in scale and power should never destroy, absorb, or take over the work of the forms of association lower down. For example, the Church should not baptize children against the will of their parents (the Church agrees), and the public schools should not undermine parental teaching about sexuality (unfortunately, they do that). On the positive side, subsidiarity implies that bigger and more powerful forms of association should be friendly and cooperative to the smaller and less powerful ones, protecting their ability to do their own jobs. Thus, the government should let families raise kids -- but keep the streets safe for families. Subsidiarity is pro-David, not pro-Goliath. It roots for the little guy. Most parents intuitively agree with it, even though most have never heard of it. By contrast, today our bosses don’t. In September 2023, a poll by Scott Rasmussen and RMG Associates, comparing the views of different strata of Americans, found that only a little more than a third of the voting public thought educational professionals rather than parents should decide what children are taught, but that two thirds of elite respondents thought so. * Back to where I began this post. The reason most often given for subsidiarity is that the whole panorama of smaller partnerships in the good life springs from the social nature of man, in such a way that each form of association has its own proper work – excluding perversions such as gangs of thieves, of course. Parents should be allowed to raise their children because they are naturally adapted to raise them, and no one else can do the job better; the basis of parental right is not “lifestyle decisions,” but that every child needs its mom and dad. What parents do for each other and for their children cannot be reassigned, nor can what friends or neighbors do for each other, or even what the members of chess clubs and craft unions do for each other. Granted, the trade union is not a natural institution in the same sense that the family is: Even so, trade unions can better maintain the standards of their crafts, and protect themselves from abuse and exploitation, than bureaucrats can. I think all this is true, but we can say much more in favor of subsidiarity. Practical wisdom is developed through experience. It was Aristotle, I think, who first pointed out that just for this reason, political prudence, or wisdom in the affairs of the community, is much more rare than domestic prudence, or wisdom in the affairs of the home. Almost everyone has experience directing his own affairs and those of his family; not many have experience directing matters on the largest scale. But the rarity of political prudence is not just a matter of scale. For not only can a man have domestic prudence and yet lack political prudence, but the converse is also true: He can have a degree of political prudence – he can be good at encouraging all those little partnerships to remain in partnership and to refrain from invading each other’s domains -- and yet be inept to govern any single one of those little partnerships. Thus, most decisions should be kept out of politics simply because they can’t be made well at that height. This is not a recommendation for anarchy, for the state too has its proper work. To continue with my Exhibit A, the family, laws are necessary to protect the peace which allows families to do their proper work; laws are necessary to protect families from others who might butt in on their proper work; and laws are even necessary to protect competent parents from intrusions on their proper work by the state itself. But we need to get out of the habit of thinking, whenever something doesn’t please us, “There oughts be a law.” ____________ Note * For purposes of the poll, elites were defined as people with postgraduate degrees who earn at least $150,000 annually and live in zipcodes of high population density. “Them vs. Us: The Two Americas and How the Nation’s Elite Is Out of Touch with Average Americans,” https://committeetounleashprosperity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Them-vs-Us_CTUP-Rasmussen-Study-FINAL.pdf.

|

Hey, Man, Stuff ChangesMonday, 02-19-2024

In the classical view, a law should be changed, not whenever we can think of an improvement, but only when the improvement is great enough to offset the harm of change in itself. A graduate student I once taught found this view baffling. What could be bad about change? Life changes. That’s how it is. That’s good. A few weeks later his girlfriend dumped him. He was devastated.

|

The Next BurningMonday, 02-12-2024

The next destruction of books will take place as swiftly as the burning of the Great Library of Alexandria. Already libraries are getting rid of physical books and shifting to electronic records. Vandals will delete electronic books by hacking the systems; politicians will delete them for the supposed protection of the republic. Selective electronic book burning will be as easy as pie, because so-called artificial intelligence will be used to scan millions of manuscripts at once for unapproved ideas. Destruction is already taking place willy-nilly, because software and hardware obsolescence increasingly deprive us of the ability to recover documents, files, and recordings more than a few years old. Can you still listen to your old eight-track tape player? Can your DVR-equipped computer still read your old CDs? Can your new computer accept your old floppy disks? The span of electronic memory turns out to be much less than a single generation of man. About ten years ago, I was about to lose access to about 15,000 old documents written in an old word processing program, because the newer versions of MS-Word no longer support DOS. Well-meaning technicians – who thought this was like bringing back the horse-drawn buggy -- told me that there ought to be a way to convert my documents all at once. Even after research, though, they couldn’t tell me what it might be. Over a period of weeks, I dropped everything else in order to laboriously convert my files one, by one, by one, by one, by one. “But everything is on the internet now!” Software obsolescence affects a lot of internet files too. Have most of us any idea how fragile such complex systems are, how much coordinated effort by thousands of people they take to maintain? Not to mention how easy they are to manipulate. Consider the algorithms used in social media, which seem so much more efficient in eliminating what our elites call “misinformation” than in eliminating children’s access to pornography. Besides – people read less and less, and the internet has devastated our attention spans. “It will all work out.” Don’t be so sure. We prefer to view prosperity, economic opportunity, political freedom, and religious liberty as facts of nature, like air and gravity. In fact they are delicate achievements which will be lost in an instant if the cultural consensus which supports them disappears. Already this consensus has gravely eroded. In fact, it is under assault, and too often, those who recognize the fact are afraid to speak for fear of being called “partisan,” “polarizing,” on “on the wrong side of history.” People of a certain kind of faith sometimes ask me, “But don’t you believe God is in control?” Yes, but this doesn’t mean that He will preserve our civilization. What it means is that He can save souls and preserve His Church, and that in the end, none of our civilization’s wickedness and insanity will be able to defeat His purposes. If we cannot or refuse to be reformed, we may be swept away -- or allowed to destroy ourselves – or, most likely, both. Cheer up. I don’t say that our civilization can’t be reformed. Gloom and doom are wastes of time and vexations of spirit. Since we don’t know the future, we should always fight to preserve our institutions, never stooping to lie or manipulate, as though we knew that they still can be preserved -- for maybe they can. Prudence, however, requires inward preparation for the very real possibility of their disappearance, well within our lifetimes.

|

Three Bad EggsMonday, 02-05-2024

First egg: Progressive educationAn advertisement for a private school in our neighborhood association newsletter reads as follows (remember, this is Austin): No grades. No homework. No teachers. Apply now. Rolling admissions. I notice that it doesn’t include “No tuition.”

Second egg: Social construction“Gender is a social construction.” No, gender ideology is a social construction. Sex is a work of nature. Gender is confusion about sex.

Third egg: Pragmatism on left and rightThe mantra of leftist humanities professors that truth isn’t how things really are, but “whatever works,” is very much of a piece with the idea of some conservatives that you don't need the humanities: Just get a business degree. One would think that even businessmen would want to pursue the great questions of life, but no. It’s come to this: The barbarians are pillaging the city, and the anti-barbarians respond that this being the case, we have to burn the city down.

Bonus: EmpowermentMeans being told that I may do whatever I want.

|

Conservative Judicial Activism?Monday, 01-29-2024

Query:As a man of the left, I think your critique of how some conservatives are abandoning their former opposition to judicial activism is on point. This theory is a power move from the right. People are getting more radicalized as we speak.

Reply:Well, thanks, but some recent court decisions seem to me not conservative judicial activism, but merely a correction of left-wing judicial activism. I don’t see it as a “power move” to correct previous power moves; quite the contrary. So I am not terribly worried. Yet. Unfortunately, though, you’re right that some conservatives really would like to see a conservative variety of judicial activism. Conservatives ought to champion the rule of law. Decades ago, the left gave up on the rule of law. Some on the right seem to have concluded that things have gone so far that they must fight fire with fire. A conservative young man visited my office some years ago and recited a long list of illegitimate, dishonest, manipulatory techniques used by the left. I said words to the effect, “I know all this. Why are you telling me?” He replied “Because unless our side does the same things, we’ll lose the country.” I answered, “If you do what is evil so that good will result, you will destroy everything about your country worth saving, and you will be just like those whom you oppose.” I’m afraid he was very disappointed in me, and left my office in sorrow.

|

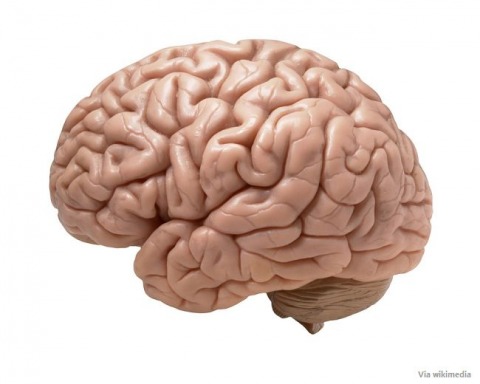

The Use and Abuse of Brain ScienceMonday, 01-22-2024

Neuroscience sometimes explains the how of a fact we shouldn't have needed neuroscientists to tell us. Often, though, the significance of the how is misunderstood. Example one. Lots of connections are still being made in the frontal lobes of the brain right through the ‘twenties. That’s not surprising. You don’t need brain science to understand that young people take a long time to develop mature judgment. Unfortunately, the fact that it takes time to become mature leads some people to the mistaken conclusion that young people shouldn’t take on any commitments or responsibilities until the process is complete. This ignores the fact that we develop mature judgment only by taking on and sticking to commitments and responsibilities. Besides, frontal lobes or no frontal lobes, good judgment doesn’t magically reach completion at age twenty-five or thirty. We are learning and relearning all our lives. Example two. A number of researchers have written that pornography rewires the brain. Of course it does. But we already knew, or should have known, that pornography is habit-forming, and this phrase merely tells us what the brain is doing when a habit is formed. All habits rewire the brain, just as all knowledge and belief do the same. Unfortunately, talk about brain wiring leads some people to the mistaken conclusion that habits are fates – that the brain makes people keep doing the same thing, so that they can’t reform their habits or get out of bad ruts. What a counsel of despair.

|

Is It Just Silly?Monday, 01-15-2024

Query:This will sound nuts -- then again, maybe not? I thought you could shine some light here if you have a moment or two. My daughter is now 18 and while she hasn’t taken to stripping, she’s got an OnlyFans subscription. Wonderful right? Thing is … its fetish based. It’s a strange world. You name it, truly. While she isn’t naked or stimulating herself or anything remotely close to what you would dub pornography … is this still wrong for her to do? Doesn’t it seem harmless and well ... a bit silly? If you have any insight at all that I can reason out please do send your input. If I talk to her about it, I’m likely to get the answer that fetishism isn’t the same as pornography.

Reply:Yes, this is certainly pornography. Sexual immorality is whatever deviates from the intended purposes of the sexual powers and feelings, which are given to us for the fruitful, personal love of husband and wife. Pornography is sexually immoral, because it consists of writing or images intended to cultivate and arouse disordered fascinations and desires. The immorality of the fetishistic variety of pornography lies in the fact that it attaches sexual desire to things, as well as to persons being used as things. It’s no accident that OnlyFans is used primarily by prostitutes for self-advertisement. Pornography and the habit of using it are not at all harmless or silly. Escape is certainly possible – but in the meantime, it subverts the imagination, reorients the desires, and alters the way people think. Those who are habituated to pornography tend to have emotional difficulty in normal relationships, because their emotions and attitudes become disarranged and they tend to develop unwholesome expectations of others. Over time, the things which first excited them lose the power to arouse, so they often turn to ever more extreme and unnatural fantasies in order to get that excitement back. We now find that among young men who use certain sorts of pornography, there has even been a rise in the desire that young women should submit to being choked. The bottom line is that you are right to be concerned, and you should not be embarrassed that your daughter’s interest in this kind of thing seems “off” to you. It is very much “off.” God bless your daughter and your guidance of her. Related:On the Meaning of Sex

|