The Underground Thomist

Blog

Is love selfish?Monday, 01-20-2014The other day, one of my students suggested that there is no such thing a morality, because to be moral is to be unselfish, and even so-called moral behavior is really selfish at the core. His example was that even a martyr isn’t acting morally, because he gains something by dying for others. It would be easy to expand the list of examples. Friendship is selfish because we get something from it; a mother’s care for her child is selfish because it makes her happy. This view is mistaken, but there are kernels of truth in every believable mistake. Otherwise they couldn’t be believable. In this case, one of the kernels of truth is that we necessarily seek our own happiness. The other is that morality has something to do with love, and love is a commitment of the will to the true good of other persons. The misstep lies in thinking that unselfishness means loving the others instead of myself. No, I must love them asmyself. For human beings, the good is of such a nature that unless we share it, we cannot enjoy it at all. To put it another way, if you think the difference between a selfish and unselfish person is that one sort seeks his own happiness and the other sort doesn’t, then of course you will think there is no such thing as morality, because everyone seeks his own happiness. The real difference between selfish and unselfish persons lies elsewhere -- in how they are related to other selves. The selfish person is indifferent to them. He thinks not caring about other selves will make him happy. This is a delusion, which makes him miserable. But the unselfish person identifies with other selves. If those he loves flourish, he flourishes; if not, then not; and so he flourishes. The greatest love is to lay down his life for them – not because he is indifferent to his happiness, but because it is inseparable from theirs. From this point of view, one might almost say that the problem with the selfish person is not that he desires happiness too much, but that he doesn’t desire it enough. If only he conceived happiness more adequately, he would not seek it in such a cramped and unimaginative way. Only the one who spends himself saves himself. Misers lose everything. |

The collapse of the universitiesThursday, 01-16-2014I closed the last post with a question: Having abandoned the vision on which the medieval university was built, what are modern universities organized around? The answer is “Nothing in particular.” They are queasy alliances of interest groups which have no ultimate commitments in common. Among the more respectable things the university tries to be are a job training center, a place for technological research, and an accreditor of fitness for employment. But universities don’t do any of these things well, and each of them can be better and more cheaply by other kinds of institution. You don’t need to go to college to learn how to manage a hotel, or to prove that you can program a computer. Government and industry can carry out technological research just as well at their own facilities. And college prepares people for employment so poorly that some corporations are now forced to run their own classes in math and English composition. The university also tries to be a place for doing things that just don’t need to be done at all, like giving young people a place to “discover themselves.” This which means giving them a place for a protracted period of dissipation while avoiding adult responsibilities. Parents who think this is the best way for their children to grow up could save money by just sending them on cruises. Universities offer places for preserving failed ideologies and validating faddish “identities,” but we have politics for that; we don’t need universities. And they are massive public-works programs for keeping a larger number of people employed as scholars than could otherwise find that kind of work. We do need scholars, but let us be honest: Most scholars would be better employed at something else. The things universities do which other institutions can do better eventually will be done by other institutions. The things they do which don’t need to be done will eventually lose public support. I will not mourn these changes. They are overdue. I will mourn the loss of the one thing universities can do well, which was done in medieval universities, but which the modern university no longer believes in: Pursuing the vision of the coherence of reality and its friendliness to the mind, and forming minds which are capable of sharing it. We will have to find another way to do that. I don’t know what it will be. I believe it will be found, but it will not be found in my time. There are signs on the horizon, but they are faint. And so to reply to Vedder and Denhart: Gentlemen, you are mistaken. These are the reasons why the college bubble will pop; this is why the higher education system will collapse. Not because it is “still tied to its medieval origins.” |

What’s wrong with universities?Monday, 01-13-2014A recent Wall Street Journal article by Richard Vedder and Christopher Denhart concludes, “Many poorly endowed and undistinguished schools may bite the dust, but America flourished when buggy manufacturers went bankrupt thanks to the automobile. The cleansing would be good for a higher education system still tied to its medieval origins – and for the students it’s robbing.” Vedder and Denhart are right about the need for reform, but they are mistaken about what kind of reform is needed. And they are utterly confused in thinking that the problem is that universities are “still tied to medieval origins.” Medieval students had to master seven elementary studies before going on to advanced degrees. The first three, called the trivium, were grammar, or the laws of language; rhetoric, or the laws of argument; and dialectic, or the laws of clear thought. The next four, called the quadrivium, were arithmetic, or the laws of number; geometry, or the laws of figure; music, or the laws of harmony; and astronomy, or the laws of inherent motion. Why these seven? Because medieval universities were organized around the view that the universe makes sense, that knowledge is grasping that sense, that the mind can really grasp it, that all knowledge is related, and that all of its parts form a meaningful whole. By contrast, our universities are organized around – what? Actually, they aren’t universities at all, because they have given up their vision, the coherence of universal reality and its friendliness to the rational mind. Most humanities scholars gave up that view some time ago. In fact, they mock it. That’s why we have so little that even pretends to be a core curriculum, and why even general education courses are a smorgasbord. The pretentious postmodernist credo is “suspicion of metanarratives,” which means no one gets the Big Story right. Of course that is a Big Story too. “Once upon a time people believed there was a Big Story which would make sense of things if only they could get it right. Now we know better, because there isn't any Big Story, so no one gets it right. And we are the clever ones the ones who got that right.” How clever are these clever ones? You tell me. Several years ago my own university sponsored a freshman assembly about choosing a major. Faculty in the humanities and sciences presented pep talks for their fields of study; student leaders asked them questions. The tone of the event was epitomized by the question, “If you were a bar of soap, whose shower would you want to be in?” Grinningly, the faculty moderator pressed the faculty panelists to answer. I am ashamed to say that they did. This is not the sort of problem which can be solved by cost-savings, team-teaching, or distance learning. Such solutions are merely economic. The problem is spiritual. Though scientists have held out longer, belief in the coherence of universal reality is vanishing among them too. The physicist Werner Heisenberg wrote in his book Across the Frontiers that “Not only is the Universe stranger than we think, it is stranger than we can think.” This view isn’t a finding of science. It’s merely a culmination of a line of thought which began with philosophers like Kant, who thought our minds can never really get at reality itself, but only at their own thoughts about reality. Having abandoned the vision of universal truth on which the medieval university was built, what are modern universities organized around? Stay tuned. * “How the College Bubble will Pop,” Wall Street Journal, p. A13, 9 January 2014. |

The rest of the witnessesMonday, 01-06-2014Last week I was telling the Original Visitor about – The Original Visitor breaks in: You don’t have to be so didactic. Budziszewski: Why do you care? You’re a figment of my imagination. But you’re imagining me to be something like a real reader, and a real reader would find your language patronizing. “I was telling him,” indeed. Sorry, that's not my intention. How would you say it? I thought we were having a little chat. All right. Last week the Original Visitor and I were chatting about the four witnesses. Better? Yes, much. May we now resume our broadcast? Yes. You were going to tell me what the third witness is. Well, you remember that we were talking about our natural design. Of course. The second witness was recognition that in fact, we do have a natural design -- I remember. So? So the third witness is just recognition of its details. What do you mean? If the human person really is a meaningful whole, then each of our various powers and features has moral significance. For example? For example, the respiratory power is for breathing, not sniffing airplane glue. So by meanings and purposes you just mean the functions of our bodily organs. No, I’m talking about all of our powers and features. The power of anger is for arousing us to the ordinate defense of endangered goods. The sexual power is for turning the wheel of the generations uniting the procreative partners. The power of practical reason is for deliberating well. The power of wonder is for stirring us up to seek truth, especially the truth about God. Each of these powers should be used according to its purpose. A little propaganda, eh, Mr. Blogger? I see how you slipped in the item about sex. I didn’t “slip it in.” We recognize the inbuilt meaning and purpose of the sexual powers in exactly the same way that we recognize the inbuilt meaning and purpose of, say – Try anger. There’s a power for you. Tell me the “inbuilt meaning and purpose” of the power to become angry, if you can. Wouldn’t you say that the inbuilt meaning and purpose of anger is to arouse us to the ordinate defense of endangered goods? Why should that be the purpose? Be serious. Apart from arousing us to the ordinate defense of endangered goods, why should there even be such a thing as anger? And I suppose you’d say, “Apart from the need for posterity, why should there even be such a thing as sex?” Would I be wrong? Why not say that the meaning and purpose of sex is simply pleasure? Because the exercise of every voluntary power is pleasurable, and that tells us nothing about its purpose. You wouldn’t say that the inbuilt meaning and purpose of the power to eat is simply pleasure, would you? You said that each of our “powers and features” has moral significance, but all of your examples are what you call “powers.” Give me an example of a “feature.” Sure: The fact that men and women are complementary. Complementary, like different? Complementary, like different in a way that makes them correspond, that makes them form a whole. There is something missing in a man which is more fully present in the woman, and something missing in a woman which is more fully present in the man. They balance each other. And why do you say that this fact about us has “moral significance”? Because any way of life which denies or defies it is asking for trouble. Every few sentences I want to hit you. Why? I don’t have any urge to hit you. Never mind. Tell me the fourth witness. When I do you may hit me anyway. Why? Because the fourth witness is all about asking for trouble. So what is it? The natural consequences of our deeds. Hmm. What do you mean by “natural consequences”? All of the things that happen to us when -- and because -- our lives cut across the grain of our design. Like what? If I cut myself, then I bleed. If I use a lot of dope, then I become its slave. So by “natural” consequences you mean bodily consequences. No, I mean all of the consequences which arise in the course of nature. If I live by knives, then I die by knives. If I desert the mother, then my child grows up without a father. If I hop from bed to bed, then eventually I lose the capacity for intimacy. If I betray my friends, then eventually I have no friends. Okay, not just bodily. You mean bodily, emotional, and social consequences. Don’t forget the intellectual consequences. Like what? If I make myself stupid, then I will end up even stupider than I had intended. Works every time. I’m not sure I understand you. You should. I’ve been talking about it for weeks. Oh, I see – those stories you’ve been telling in your blog – Yes? Most of them are about the natural consequences of suppressing conscience. Right? Right. So they’re about the natural consequences of making yourself stupid. Yes. But then they’re not about just one witness. No. They’re about two witnesses at once. The first and the fourth. Deep conscience and natural consequences. Right again. So the four witnesses don’t work independently. They depend on each other. They interact. We need all four. Exactly. Do you notice how that takes us back to the question you asked at the beginning of the conversation? That was last week. What was it again? You asked why what I call natural law doesn’t sound much like what thinkers like Hobbes and Locke called natural law. Oh, right. I said I work in the classical natural law tradition, but they were revisionists. So you asked about the difference. You’re going to tell me that thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke got natural law wrong because somehow or other they got the four witnesses wrong. Correct? Yes, but it’s even worse, because the revisionists didn’t even admit that there are four witnesses. You see, they were simplifiers. What do you mean? The hallmark of classical natural law thinking is that it tries to weave all four witnesses into a tapestry. So you’ve been saying. But the revisionists tried to make their tapestries with fewer colors. They always ignored or diminished at least one of the witnesses. Illustrate. Use Hobbes. His theory recognized only one of the four witnesses. Natural consequences? Right on the first try. Not only that, he recognized only one kind of natural consequence. Violent death. Right. He considered man’s natural condition to be anarchy. But in anarchy life was short. According to him, we worked out moral laws in order to stay alive, and we invented government to enforce the moral laws. But that’s not all wrong, is it? Morality does help keep us from each other’s throats. It does. And government does enforce – never mind, I don’t want to say that. Still, isn’t there something to be said for keeping one’s theory simple? Occam’s Razor and all that. Why clutter up the picture with unnecessary details? Because they aren’t all unnecessary. You’re saying the revisionists threw out some moral data. Actually, a lot of it. And I suppose throwing it out had natural consequences too? Yes! When you push some of the facts out the front door of your theory, you force them to try to creep in through the back door. Worse yet – Go on. Worse yet, they may not succeed. At what? At creeping back in. You’ve lost me again. Would you mind not being found until next week? |

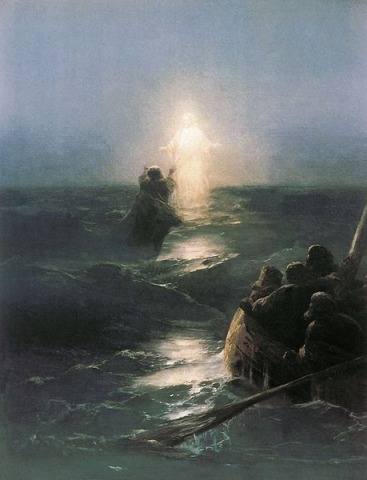

MiraclesSaturday, 01-04-2014

"Somehow or other an extraordinary idea has arisen that the disbelievers in miracles consider them coldly and fairly, while believers in miracles accept them only in connection with some dogma. The fact is quite the other way. The believers in miracles accept them (rightly or wrongly) because they have evidence for them. The disbelievers in miracles deny them (rightly or wrongly) because they have a doctrine against them." -- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

|

Revisionists, and why I’m not one of themMonday, 12-30-2013The Original Visitor: Hello. I’m back. Budziszewski: Good morning. Haven’t heard from you since blog post number one. I thought you’d lost interest. I never left. I’ve just been lurking. Reading your posts in the shadows. Be my guest. Besides, it isn’t as though I’m your only visitor. And you know this? I know many things. I even know that visits to your website spiked on December 9th. How do you come by this knowledge? I’ve hacked your website statistics. Can all of my figments of imagination hack my data? Probably not. I’m talented. What brings you out of the shadows now? I’ve been trying to figure you out. What’s to figure out? My blogs are pretty straightforward. Well, for a guy who calls himself a philosopher, you tell an awful lot of stories. I thought you’d spend more time proving theorems or something. Do you mind answering a few questions? Ask away. For starters, why do you call yourself a natural law thinker in the first place? Didn’t I make that clear in our previous conversation? Sort of. But the things you say don’t sound much like what other natural law thinkers say. Natural law thinkers like who? Like the ones my teachers made me read in college. Thomas Hobbes. John Locke. Weren’t those the big guns? The state of nature and the social contract and all that jazz. I see the problem. You’re right. I’m closer to Locke than to Hobbes, but what I call natural law doesn’t have much in common with what either one of them meant by the term. Why not? Because I hew to the classical natural law tradition. Those fellows were revisionists. Tell me the difference. The revisionists pulled the classical tradition to pieces and threw most of its intellectual equipment out the window. Those implausible ideas that you mentioned -- the thoroughly unnatural “state of nature” and the thoroughly unhistorical “social contract”? They were the things they used to plug the holes. What did they throw out? Some metaphysics, like the concept of real essences. Some philosophy of mind, like the distinction betweenconscientia and synderesis. Lots of things, actually. You’re losing me. Didn't you see that blogger who said your blog would "make your head hurt"? Yes, but I thought he was complimenting me. Give it a rest. Can’t you just talk common sense? The terms I used are for talking about common sense more precisely. Forget the toolbox. Use street language. Talk with me like a guy at the bus stop. Okay, let’s try this. Four deep considerations run through all of classical natural law theory. We can call them the four moral witnesses. I mentioned them the first time we talked. Except then you called them roadsigns. Right. Go on. What are these four witnesses? The first one is deep conscience, which provides the starting points of all moral reasoning -- principles which don’t have to be proven, but which we used to prove everything else. For example, I don’t need a proof to know that equals should be treated equally; the principle is evident in itself. Maybe conscience is just a way of thinking we can’t escape. Maybe if we’d evolved differently, we’d have a different conscience. You’re asking whether the contents of conscience are arbitrary. Whether they could have been radically different. Right. But we don’t experience ourselves as blooming, buzzing, patched-tegether confusions. We experience ourselves as meaningful wholes. Even if some of the meanings are elusive at times? Yes. It’s because we experience life as meaningful that we’re troubled when meaning eludes us. We regard the sense of meaninglessness as an aberration. And that’s the second moral witness: Recognition of the designedness of things. Maybe we just evolved a belief in meaning. I take it that this belief would satisfy a pre-existing need for meaning? Yes. And that need evolved too? Yes. In that case the need to believe in meaning must have adaptive value. Tell me what it is. If you believe your life has a meaning, you’ll try harder to survive. You’re assuming what you set out to prove. How? Belief in meaning would motivate you only if you already had a need for meaning. Why should we first evolve a need to believe in a meaning which doesn’t exist, then evolve a tendency to believe that it does exist? You could save a lot of time by not evolving either a need for meaning or a belief in it, and just evolving an urge to survive. Hmm. For purposes of argument, I’ll let that stand. You mean you can’t answer me. No, I mean I want to get on with it. Even if we do recognize “the designedness of things,” tell me why you call it a “moral” witness. What does it have to do with knowing right and wrong? For one thing, it vindicates the previous moral witness. Vindicates it in what sense? If everything in us is meaningful, then conscience is meaningful too. It’s not an illusion; it really does witness to morality. It is an inward testimony to God’s law. Stop. What’s the matter? How did God get into this? I thought you said you’d been reading this blog all along. I have. But we’ve been over this. If things are designed, then Someone must have designed them. I thought the whole point of natural law being “natural” is that it made recourse to God unnecessary. Don’t atheists have consciences too? Yes, but they can’t account for them. If they are consistent, they will insist that human beings are the arbitrary result of a process that did not have us in mind, and that conscience is nothing more than a residue of that process, just as meaningless as the rest of it. Have you heard of George DeLury? I’ve never heard of a philosopher by that name. Not a philosopher. A wife-killer. He drugged and suffocated her. After he was released from prison, he wrote about the pain of his remorse. But he said that it meant nothing, because it expressed only a primate inhibition against killing our own kind. Hmm. So you’re saying that the second moral witness is a moral witness because makes the first moral witness count. Yes. And if there really is a Designer, then I suppose you would say that we should be grateful to Him too. Assuming the principle of gratitude. But I suppose you’d say that the principle of gratitude is part of what deep conscience testifies to. Yes. To be continued. |

The Skeptic as PenelopeMonday, 12-23-2013Last week I told about my conversation with Standish Wanhope (of course that's not his real name), my table mate at the opening dinner of a conference, who had pushed his atheism so aggressively throughout the meal. At the closing dinner he was strangely different. Perhaps it was because the conference was finished, and he no longer had to mark his territory. Perhaps it was because he had already had a few glasses of wine. Perhaps it was because the geography of the table brought more people into the conversation. Perhaps it was because at this final dinner I was joined by my wife, who can talk with anyone in the universe, though she prefers not to be quoted in blogs, and I respect her wishes. At first Standish was engrossed with a different group at the table, but when he overheard someone in our own covey say something about religion, he turned away from them and joined us. With characteristic directness, he asked us our religious affiliations. We told him. He settled himself into the covey and exclaimed “I’m very religious.” This hardly squared with his protestations of atheism during the opening dinner, and I was more than a little surprised. His speech changed too, acquiring a mellow and teacherly quality. He told us that during his boyhood he had belonged to one of the old-line Protestant denominations, of which he had fond memories. He had fallen away in his teens, he said, because he couldn’t find a reason to believe in God. The statement seemed strange to me. “If you need a reason to believe that God is real, then shouldn’t you also need one to believe that He isn’t? Why is the burden of proof on the theist?” “I don’t say that I know God doesn’t exist,” he answered. “I’m not an atheist, I’m an agnostic.” I responded, “But aren’t you an atheist in practice? Although you claim not to know whether God exists, you base your life on the assumption that He doesn't." He accused me of not carefully listening. “I don’t assume that God exists or that He doesn’t exist. Between belief in God and disbelief in God, I’m neutral.” That didn’t seem right. “I understand that you view yourself as neutral. I only suggest that you aren’t. Not really.” “But I am. For all I know Christianity might be true, and for all I know it might be false. I have no information either way.” “The difficulty with that line of reasoning is that it presupposes that Christianity is false,” I replied. “How can not having any information whether Christianity is true presuppose that it isn’t true?” “Because Christianity denies that you have no information bearing on the truth of its claims,” I suggested. St. Paul had argued that the problem isn’t that people are ignorant of God, but that they suppress their knowledge of His reality. So if Standish believed himself ignorant, he must think that at least this Christian claim is false. Perhaps I had hit a nerve, or perhaps I was merely too persistent, for he promptly diverted the entire line of inquiry. “My lady friend and I have very deep conversations about political and religious subjects. It’s so important to be able to share your deepest concerns with someone.” I’m sorry if the words seem made up; I’m quoting him as closely as I can. At any rate, the diversion succeeded, and conversation in our conversational clump meandered for a time. When at some point it meandered back to the question of what is true, again he diverted the stream. “I have a deep, rich secular humanism.” His voice deepened, as though he were an actor on a stage. “I’m oh, so wonderfully satisfied with it.” And then there was the point in the conversation when he asked, “What do you think of the new religious music? To me it’s just watered-down Simon and Garfunkel. Give me the fine old traditional hymns any day.” I had to smile. You couldn’t not like Standish. At least you couldn’t not like this Standish. How the two of him fit together wasn’t clear, because this one contradicted everything the one at the opening dinner had insisted upon. He was like Penelope, unraveling at night what she had woven during the day. “Where do you hear the new music?” “Why, in churches.” “So you visit churches sometimes.” “Yes. But isn’t the new music awful?” “I confess I’d find a steady diet of it difficult. What music do you prefer?” “You know — the great old songs like ‘Rise Up, Ye Men of God.’” “Yes, that one sticks to your ribs. What do you like about it?” “It stirs you up. Makes you want to stand and be counted.” “But for a cause in which you don’t believe.” “I told you that I was religious.” “I have a colleague like you. He’s an atheist, but calls himself an ‘aesthetic Episcopalian.’ He believes in the ritual, but not in the religion.” “You aren’t understanding me,” he said. “Let me tell you something you would never guess. My elderly aunt is a person of deep faith. What a great lady. I still visit her sometimes. It’s a moving experience. When I’m with her and she speaks about the Lord, I say ‘I believe.’” “But you don’t believe.” “When I’m with her, I do.” “Then why not when you’re not with her?” “Because I have no rational basis for belief. It’s feelings. Feelings aren’t knowledge.” “Like your feelings about the grand old Christian hymns.” “Yes. I miss them terribly.” He told us he’d been thinking about joining a church choir. Or perhaps that he had already joined it; memory fades. I think he said he did sing with them sometimes. “You would join a church choir without joining the Church?” “Yes. Just to be able to sing them again.” Just to be able to sing them. Just to be able to sing them as though they were true. That was pretty much where the evening ended, but of course one can’t stop wondering. I wondered why Standish had really walked away as a teenager; whether at some level, he knew that everything he had walked away from was really true; whether the religious feelings which disturbed the complacency of his would-be-atheism were the natural accompaniment to that knowledge. Believers are said to have crises of faith. I think Standish, God bless him, was having a crisis of faithlessness. Merry Christmas. |