The Underground Thomist

Blog

Climate ModelingSaturday, 01-16-2016

Concerning climate change, here is another lesson, which has stuck with me ever since the days when I thought I wanted to be a mathematical modeler in another field. You can always build a model that predicts everything that has already happened. That doesn't mean you can predict what is going to happen.

|

Nebuchadnezzar’s Civil ServiceSaturday, 01-16-2016

I would advise any young Christians who are considering a career in government, irrespective of branch, at any level, from low to high, that before any other study they read the first six chapters of the Book of Daniel: Thoughtfully, very carefully, and in the context of the Exile. Mutatis mutandis, of course: Making the necessary changes. Paganism is not the same as neo-paganism; the times before Christ were not the same as the times after. And the literary genre of the book is strange and difficult for us. But the times for which it was written are very like the ones we are in.

|

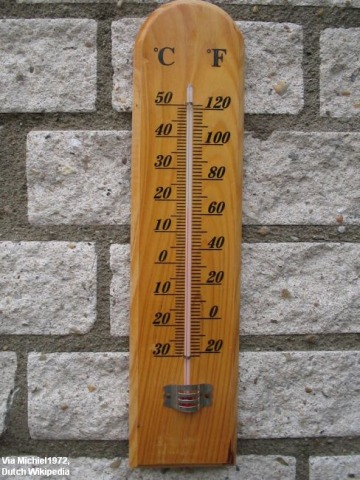

It’s Cold Out ThereFriday, 01-15-2016

An acquaintance tells me that in his part of the world, which would normally be warm this time of year, the weather is unusually cold. If it’s shivery where you are, this may amuse you: The next time someone comments on the cold, quietly murmur “Climate change,” then watch for the reaction. I don’t claim to know whether the globe is getting warmer. I do know that for scientists who live on money from the government, it’s a beautiful hypothesis. No conceivable evidence can disconfirm it. Hot weather or cold, rising global average temperatures or stable ones, favorable data, unfavorable data, or no data at all – it’s all good.

|

HedonismThursday, 01-14-2016

Philosophical hedonists think that in the final analysis, the good is nothing but what we desire, and the only thing we actually desire is pleasure. Did you think you desired love, knowledge, meaning, friendship, or friendship with God? No, you only desire the pleasure of those things. Most of my students find this argument irresistible. They have all seen movies like The Matrix, so to provoke them to look deeper, I used to pose this puzzle: “Suppose someone invented a system of illusions you could be plugged into, with sights, sounds, sensations, and memories so photo-perfect that you thought you loved real people, you thought life was meaningful, you thought you were enjoying friendship with God – in fact, whatever you want -- but actually all these impressions were being fed into you by electronics. The inventor offers to plug you into his device for the rest of your life. Do you accept the offer?” Over the years, the number responding “No, it wouldn’t be real” has declined, and the number responding “Sure! What’s real anyway?” has increased. So I’ve upped the ante. I’ve dropped the distraction of virtual reality. Now I say, “Suppose a surgeon offers to strap you onto a gurney and implant a tiny electrode implanted into the pleasure center of your brain. You will stay on the gurney forever, but with just a few microvolts of carefully monitored current, you will experience the greatest possible pleasure, and a glucose drip will keep you alive so it goes on and on until you die of old age. You won’t think you are loving someone. You won’t ask whether anything has meaning. You won’t think you enjoy friendship with God. The only thing you will be aware of is all that pleasure. Now do you accept the offer?” Fewer answer “Yes” than before. But you’d be surprised by how many still do. All sorts of philosophical fallacies are wound up in that reply, for every pleasure implies a good different than itself – the pleasure is the experience of repose in that particular good. Hallucinating pleasure is not the same as experiencing it, any more than hallucinating a cat is the same as seeing it. In one case, the cat isn’t there; in the other case, the good isn’t. Yet I can’t help but think that the problem is not just an error in reasoning. What kind of society have we made, that comfortably brought-up young people can prefer death-in-life to life?

|

Change of Heart in ConfuciusWednesday, 01-13-2016

After speaking of the duties between sovereign and minister, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger, and friend and friend, Confucius writes gracefully, “Some are born with the knowledge of those duties; some know them by study; and some acquire the knowledge after a painful feeling of their ignorance.” By those who come to know these duties “after a painful feeling of their ignorance,” I would like to think he means those who experience repentance and change of heart. Even such a slight and passing allusion to such things is rare outside of revelation. One is refreshed, as by a breeze from heaven. On the other hand, the sage goes on to say, “Some practice them with a natural ease; some from a desire for their advantages; and some by strenuous effort. But the achievement being made, it comes to the same thing.” These words contain not even a trace of awareness of divine grace – especially of the transformative importance of the motive divine of charity. To pursue virtue from a desire for its advantages seems to miss the point. Source: Confucius, The Doctrine of the Mean

|

Which Diversity Matters (If Any)?Tuesday, 01-12-2016

Julie R. Posselt, an assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education at the University of Michigan, has written a new book, Inside Graduate Admissions, about what she observed after obtaining permission to sit in during the meetings of the graduate admissions committees of six highly-ranked departments at three research universities and interview some of their members. I haven’t yet read the book, but it sounds interesting. One of Professor Posselt’s themes is widespread discrimination in admission in favor of everyone but East Asians, against East Asians. I don’t know whether the author herself is upset about this, but some of the reviewers are; they seem to view it as a blow against “diversity.” That’s nonsense, of course. In my experience, the professors on graduate admissions committees really do believe that they should admit grad students of many different ethnicities and colors, and that’s why they discriminate against Asians. They don’t want lower-scoring non-Asians to be squeezed out. I am against double standards too, but for a different reason: Merit. If Asians dominate college admissions so that non-Asians are squeezed out, so be it. Maybe it will motivate non-Asians to work harder. The one kind of diversity that does have some claim to consideration in admissions is diversity of thought. However, this is the sort of diversity that professors don’t believe in. One of Posselt’s anecdotes is most revealing. Admissions committees give enormous weight to GRE scores, and the applicant under consideration certainly looked good by that criterion. The committee also acknowledged that her personal statement reflected the capacity for rigorous independent thought. However, she came from a small religious college. One committee member complained that its faculty were “right-wing religious fundamentalists.” Another joked that the school was “supported by the Koch brothers.” The committee chair said “I would like to beat that college out of her” and asked whether she was a “nutcase.” She wasn’t rejected during that round, but she was during the next. I have found this sort of thing to be all too typical. It may seem bizarre that even though the members of the committee were being observed, they made no effort to conceal their malice against religion. But this is easy to explain. A great many university liberal arts professors view religion as the very definition of bigotry, and dogmatic rejection of faith as the very definition of open-mindedness. It would never occur to most of them that they might seem narrow-minded to an observer. The notion of a bigoted secularist would seem to them a strange paradox. That is why when religious students write to me for advice about getting into grad school, I tell them don’t mention your faith. They can’t be saved from battles, and shouldn’t be; but with luck, the battles can be delayed until they get their foot in the door. Then cry reason and let slip the dogs of argument.

|

Putting a Burr under His SaddleMonday, 01-11-2016

Today is another reader letter day.Question:During the holidays, I had the opportunity of visiting my hometown and attending a high school reunion. Since it was a Christian school, naturally there was a religious service preceding the reunion proper. One of the organizers -- who did not participate in the service -- approached me afterward to express pleasure that my wife and I participated. His nonchalance struck me, and I guess he must have noticed, because he immediately continued, “I really like what faith can do in a person's life. I obviously don't want to talk with you about this, but I definitely no longer believe in religion.” I asked why he had lost his faith. His answer, which left me mute, is the reason why I'm writing to you. He said: “I've had a good life, therefore I've had no need for religion. I'm sure if I'm ever in problems I'll be able to find comfort in our faith -- I know it's the right thing to do.” After that he excused himself and left to take care of something. I would really like to help this old friend find his way towards what he already knows is “the right thing to do”. How would you recommend I approach the subject? And what could I tell him? Reply:Your friend makes three puzzling remarks: 1. That he doesn’t believe in anything. 2. That he has no need for “religion,” because he has had a good life. 3. That if is ever in trouble, he will seek “comfort” in the faith. I can see why you were nonplussed. You might begin simply by telling him so, and asking whether he would mind if you asked a few questions. Since he gives mixed signals – though he said “I obviously don't want to talk with you about this,” he initiated a conversation about it – you shouldn’t press him if he declines. But if he is willing to hear your questions, then his answers will give you openings to go further. In response to his remark about not believing in anything, you might say, “Maybe you just live day by day, but unless you believed something, you wouldn’t even know how to live day by day. So what do you really believe?” Or perhaps, “I guess you mean you don’t know whether or not there is a God, but you are living as though there is no God. How do you know whether to live as though there is, or as though there isn’t?” Or even this: “It’s impossible not to have any beliefs about anything. Do you mean that although you hold certain beliefs, you have no hope about anything?” In response to his remark about not needing “religion” because he has had a good life, you might ask, “What do you mean by a good life? Do you mean the life that God considers good? Do you mean you have no sin?” Or perhaps, “You say the faith is right, but the faith claims that since God is our ultimate good, without Him we have nothing. Why are you willing to settle for anything less?” Or even this: “When you say you have had a good life, do you mean you have good things? Don’t they leave something to be desired? Haven’t you ever thought, ‘There must be something more’?” In response to his remark that he will seek “comfort” in the faith if he ever falls into troubles, you might ask, “Do you mean that the only reason to pursue God is to have psychological comfort when things become empty? In that case, isn’t your real god psychological comfort?” Or perhaps, “Suppose you did fall into trouble. Since you say you don’t believe in anything, how could you find comfort in God?” Or even this: “If you do think following God is the ‘right thing to do,’ why wait until you get in trouble? Why not do it now?” Don’t let your friend put you on the defensive. In a kind way, put him on it. I don’t mean that you should badger him, which would only make him run, or that you should load him up with theological arguments, which would only make him argue. But do ask gently pointed questions. He needs to be put on the spot; after all, he is the one who insists that he can build his house on sand. The discussion may end inconclusively, because it will not take him long to realize that he has no good answers. That’s all right. If he wants to end the conversation, let him end it. You only need to put a burr under his saddle -- to disturb his complacency.

|