The Underground Thomist

Blog

Why Should We Obey the Natural Law?Wednesday, 11-25-2015

Why should we obey the natural law? Some people say, "Because it is the law of our nature. To aspire to the good is not to conform ourselves to something alien to us, but to fulfill the requirements of our own flourishing." Other people say, "Because it has divine authority. Our nature contains the possibilities of good that it does contain just because it is the creation of God." But the mainstream of the classical natural law tradition has held that these two views are not competitors, but complements, because man is ordained to a twofold final good. The goods available to us by the exercise of our natural powers, such as friendship, family, and knowledge, are good in themselves, yet not enough. Don't we know this by experience? One would think that the better these things are, the more satisfied we would be. Actually, the better they are, the more they stir us up to long for Something More, of which they are only glimpses. Dante knew that. It was the whole point about Beatrice. The glory of this redeemed woman was reflected glory. We cannot finally be satisfied by any love short of divine love, by any vision short of the vision of God Himself. Here is the catch. The supreme good of knowing God is available to us only if we are lifted beyond our natural powers by grace. Our nature is fashioned with the potentiality to receive this gift, but it cannot provide it for itself. All merely human attempts to partake of the divine nature, to become superhuman or transhuman, are merely idolatries which end in disaster. Consequently, any account of human nature that treats God as just another natural good misses the point, and any natural law theory that stops with nature, rather than beginning with nature, is going to overlook the most important things about us.

|

Addiction and ViceTuesday, 11-24-2015

Whether compulsive behaviors like using pornography or sex-hookup apps should be considered addictions is still under debate. Most of the debate concerns brain chemistry, but one does not have to be a neurophysiologist to see why the analogy with addiction is attractive. Like drunks, people who practice these behaviors aren’t happy. But like drunks, they sometimes think that they are happy. Frequently, like drunks, they don’t want to change. But like drunks, even when they do want to change, they find it difficult to do so. On the other hand, can’t all these things be said of every vice? Cowards aren’t happy, but they sometimes think that they are. Habitual liars aren’t usually interested in becoming honest, but even if they are, they find it tough. For that matter, shouldn’t we expect everything we do to change our brain chemistry? We aren’t disembodied spirits, but body-and-soul unities. I am not suggesting that there aren’t any true neurological disorders. Of course there are. But the problem with medicalizing the discussion of everyday human action is that it takes personal responsibility out of the loop. For tens of centuries, long before we knew anything about the brain, we’ve known that every choice we make changes our predispositions toward the next one to be made. That doesn’t mean we aren’t making choices.

|

Graduation JittersMonday, 11-23-2015

Question:I am a graduating senior with a major in social work. As of May, I will be on my own and needing to go somewhere. However, my destination is unknown. I have applied to graduate school, only to give myself another choice. I have been praying that God will show me where He wants me to go, but I can't seem to find any clear direction. I have committed myself to doing whatever He wants me to do, but even though I hate to admit it, I am growing impatient. Do you have any advice for me? It's obvious that I need all the help I can get. Thanks! Reply:I wonder what you mean by "my destination is unknown"? Maybe just that you don't have a job yet -- but I think you're telling me that you aren't sure what you really want to do. Well, there are a number of possible reasons for your anxiety. Here are a few of them. (1) You just have butterflies. (2) You like social work, but have good reason (I mean more than just butterflies) to think you won't be able to succeed in grad school. (3) You never did plan to pursue a social work-related profession, because you had expected to be married by now. (4) You’re beginning to suspect that the world view promoted in secular social work programs is antithetical to Christian faith, and you’re rightly uneasy about it. (5) You had planned to pursue a social work profession, but for one reason or another you've changed your mind. Let’s discuss each of these possibilities in turn. As to possibility 1, butterflies aren’t unusual as graduation day approaches. I realize that knowing this won't make them disappear, but perhaps it may keep you from adding to them by thinking "I'm not supposed to feel this way!" If your anxieties have no further basis, they'll probably fade, and you needn't think you need to change your plans. The sheer discrepancy between a ceremony that says "You're finished" and a professional program that says "You're not" gets some people down too. If that’s the only problem, take heart, because as you begin new studies and make new friends, that feeling will probably pass too. If you fall into category 2, the answer to your dilemma is plain: Find out what kind of work an undergrad social work degree does qualify you to do without continuing. Your teachers may or may not be able to tell you. Try them, but by all means speak to a career counselor too. Most schools offer skills assessment and career counseling services; for a fee, so do some private companies. If your school has weak career counseling services, consider going to a private career counseling service, but research it thoroughly first. By the way -- don't assume that the only work a social work major can do is work which resembles social work. A good career counselor will be able to suggest fields that you might never have considered on your own. You may also find that you have job-related knowledge or talents which are unconnected with your major. So be flexible. If you're in category 3 -- you never planned to pursue a social work career because you had expected to be married by now -- seeing a career counselor is a good thing for you too. Practically speaking, this situation and the last one are the same. In both cases, you've got some training, you don't want to go further with it, and you need to find out what you can do with the training you've got already. As to possibility 4 -- what can I say? The world view promoted in secular social work programs is antithetical to Christian faith. If those are the only kinds of programs that you’ve heard of, what you need to do is find a graduate program that isn’t like that. Just for illustration, you might look into the Institute for the Psychological Sciences in Arlington, Virginia. But what if you fall into category 5? What if you need to make a flight plan change because although you used to want to do social work, you've realized that you're just not cut out for it? In this case too you should talk with a career counselor -- but you need to do something else first. What is the Something Else? Inventory your resources. After all, you're about to choose a different career than you had originally planned. Some changes might require you to put off graduation, or to get into a longer or more expensive graduate program than the one you would have entered otherwise. Look before you leap! Will you be able to afford the extra time or expense? I don't know whether you're rich or poor, whether you're a first-time or a returning student, or whether you support your parents or they’ve been supporting you. These things constrain your field of choice. Finally let's turn to God. You're getting impatient with His seeming silence. Why doesn't He direct you? Most people at your stage of life have an unrealistic view of God's direction. They're waiting for a voice in the ear, a tap on the shoulder, a dream, a sign, a special feeling. There is a reason these means of divine communication are called "extraordinary." God saves them for times when He needs to bonk someone on the head. Even then they must be tested to make sure that they really come from Him; most such experiences don't. As Paul wrote to the Thessalonians, "Test everything." (1 Thessalonians 5:21). What then is God's ordinary means of communicating His will? Scripture calls it Wisdom. "Wisdom is the principal thing," says the book of Proverbs; "therefore get Wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding" (4:7, KJV). How then do we get Wisdom? If we live in obedience to Him, following His ways and doing all the things we already know He wants us to do -- like trusting Him, talking with Him, studying His word, following His laws, thinking about His ways, worshipping with His people and showing compassion to those whom He puts on our path -- He gradually illuminates our thinking, sharpens our discernment, and deepens our understanding. That is getting Wisdom. In short, God usually works through rather than aside from our deliberations, in our minds rather than apart from them. This is the privilege of having a rational soul. It's not for nothing that He commands us to love Him all our heart, soul, and strength and all our minds. Christ "takes every thought captive." This is part of the meaning of conversion, which lasts your whole life. And as you have already discovered, it also tests our patience and our faith. The spiritual purpose of a test isn't to tell God about you –- He knows all about you already. It’s to reveal to you things He needs you to know about yourself. So don't wait for the bonk on the head. He is guiding you already. Not with fireworks, not with special feelings, not with angelic visitations, but by His own methods, which are better.

|

Can’t Decide Which One Is BestSunday, 11-22-2015

I was a math and science kid, and still love physics jokes. Don’t worry, I don’t do this too often. Question: What do you get if you cross Schrodinger's Cat with Pavlov's Dog? Answer: A pet that salivates when you ring a bell. Or does it? Heisenberg is speeding down the highway. A cop pulls him over and says “Do you have any idea how fast you were going back there?” Heisenberg says, “No, but I know where I was.”

|

Racism, Left and RightSaturday, 11-21-2015

It is a wise and beautiful thing to allow people of many kinds and origins to enter and become part of our country in search of a better life. It is a wise and prudent thing to regulate the inflow of new residents to make sure that terrorists are kept out and that the newcomers are brought into our institutions. Why is it so difficult to say both of these things at once? For two main reasons. Because on one side, demagogues curry favor with crude nativists who want to keep Those People on the other side of the fence. The Left is correct to say this. Because on the other side, the party of the State angles to enlarge the underclass of clients whom it happily keeps in permanent dependence on itself. The Right is correct to say this.

|

Cribbing from the Pagans?Friday, 11-20-2015

The analytical philosopher Peter Geach remarks in his book, The Virtues, “The profane habitually say (I read it recently in a school textbook of my daughter’s) that the Law of Moses was not given by God but cribbed from the code of Hammurabi: They never seem to have noticed that the code of Hammurabi systematically discriminates between gentlemen and commoners, whereas the Divine Law lacks the very notion of a gentleman.” We might add that the same sort of thing is said about the New Testament haustafeln or "household codes” – the rules for husbands and wives, parents and children, and masters and servants. The profane habitually say that St. Paul wasn’t inspired by God but cribbed them from the domestic handbooks of the Stoics: They never seem to have noticed that the Stoic household codes systematically subordinate the low to the high, whereas the Apostle commands both low and high to “be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ.” The form that submission takes is different for high and low, but a greater burden is laid on the high. Husbands, for example, are to lay themselves down for their wives as Christ laid himself down for the Church; wives only have to obey. Nothing like this appears in Stoic teaching, where the aim is not mutual submission, but submission.

|

The Ultimate Roots of JusticeThursday, 11-19-2015

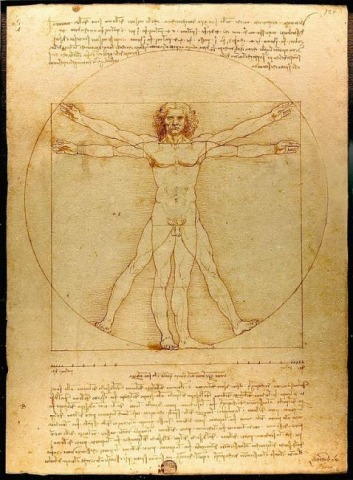

“Man ... is a person -- a spiritual being, a whole unto himself, a being that exists for itself and of itself, that wills its own proper perfection. Therefore, and for that very reason, something is due to man in the fullest sense, for that reason he does inalienably have a suum, a ‘right’ which he can plead against everyone else, a right which imposes upon every one of his partners the obligation at least not to violate it. Indeed, man’s personality, “the constitution of his spiritual being by virtue of which he is master of his own actions,” even requires (requirit), says Thomas, that Divine Providence guide the personality ‘for his own sake.’ Moreover, he takes literally that marvelous expression from the Book of Wisdom: Even God Himself disposes of us ‘with great reverence’ (cum magna reverentia) ... [If] man’s personality is not acknowledged to be something wholly and entirely real, then right and justice cannot possibly be established. "Nevertheless, even establishing them in this way still does not get at their deepest roots. For how can human nature be the ultimate basis when it is not founded upon itself! ... We must learn to experience as reality the knowledge that the establishment of right and justice has not received its fullest and most valid legitimation until we have gone back to the absolute foundation; and that there is no other way to make the demands of justice effective as absolute bounds set the will to power. "This means in concrete terms: Man has inalienable rights because he is created a person by the act of God, that is, an act beyond all human discussion. In the ultimate analysis, then, something is inalienably due to man because he is creatura. Moreover, as creatura, man has the absolute duty to give another his due.” -- Josef Pieper, “Justice,” in The Four Cardinal Virtues

|