The Underground Thomist

Blog

Pitch for Switch Hits GlitchMonday, 10-19-2015

Question:I'm at a vocational crossroads. Recently I earned an M.S. in electrical engineering. Since I began college, though, I've also been interested in apologetics and philosophy. I've done a lot of reading, taken a few classes, and taught introductory apologetics at my local church. My wife and I even moved near a seminary so I could work part-time in engineering while also studying there. My goal was to get an M.A. in philosophy, then work part-time as director of Christian education for a church as well as part-time in engineering. For a while that went all right, but after my dad died, my wife and I moved back to my home state and moved in with my mom to be close to her. The new plan is going fairly well; we have a decent size house and my mom and my wife get along well. I plan to continue my degree through the seminary's distance education program. At least until this summer, my mom is willing to support us with the money from my dad's retirement, so that this spring I can try full-time study and see if I'm cut out for it. A few days before we moved, though, my mentor at the seminary threw a wrench into the plan. He called me up and said he didn't think I should move at all, either for my sake or the school's. His reasons were that I was doing brilliantly, that I was a good influence on the rest of the students, and that he thought I ought to be a professor myself. He thinks I should aim higher than being a lay teacher, and envisions me becoming someone like him -- a person who teaches hundreds of others to be lay teachers. My family and friends think the professor line is a good one, and that working on switching devices the rest of my life seems pretty dull. Besides, part-time engineering jobs are hard to find; though I had one before, I haven't found one here. On the other hand, I feel guilty about this possibility of a "call" to the academic life. After all, I have to provide for my wife and future kids, and being a professor is less financially secure than being an engineer. I also feel that I should be reading all the time, which taxes my relationship with my wife because it makes it difficult to relax and spend time with her. She doesn't work, but is going to be studying Latin and volunteering and helping with the house. Tonight she asked me if I could help with the dishes. I said no, because I thought my time would be of more use studying and her time doing all of the cleaning. How can I know whether I could do well as a professor? How can I know whether my original career plan would be better? How should I deal with this guilt that I'm feeling? And how long should I go on living with my mother? Considering that she doesn't have any physical or financial needs right now, is that last question even important? Probably I need to be thinking about other questions too, so please tell me what you think. Reply:Let's start with the vocational questions. As I see it, there are two of them. One is about substance: Should you leave engineering and pursue further graduate study with a view to becoming a seminary teacher? The other is about process: Is it necessary or wise to make your decision about this right now? The process question is easy. Vocational decisions should never be made abruptly. All right, I make an exception in case of voices from burning bushes, but you haven't heard one of those. I can understand your seminary mentor's regret to see you leave -- it will make his life less interesting -- but frankly, he did you a disservice to throw you into turmoil at the last minute. Discerning the call of God requires time, reflection and experience. If God were telling you something that required an instant response, like "Get out of Dodge," I think He would have used extraordinary means to make clear that the message was really from Him. Once that question is settled, the other question looks different. Actually, it's premature. Instead of asking whether you should change careers, you should ask whether you're in a position to decide. The answer is that you aren't -- yet. Sure, compelling reasons for a change in career may accumulate, but they haven't; you haven't given them enough time. Consider: You've prepared for years to do engineering. Don't you think you should give it a chance before getting out of it? The fact that your friends and family think working on switching devices would be boring is irrelevant. They aren't the ones who would be working on them, and some people love that kind of work. It must have held some interest for you, or you wouldn't have gone into that field. What you find interesting is far from being the only data relevant to considering what God made you for –- but it’s part of the data. If you're still worried about being bored, here's a test. Work at your profession full-time for a few years. If the work you’re bored, you'll know it, and if you're not, you'll know that too. I'd give different advice to a freshman trying to choose between majors, because he doesn't have that option. He can't try out the work; he has to make a guess about whether he would like it. But you're not a freshman, you're a graduate, and you do have the option. So use it. You feel guilty about considering a career change because professors make lower salaries than engineers. That needn't trouble you. Your family won't starve either way. On the other hand, you do need to think more seriously about three other things.

Taken together, what these three points tell you is "Stop trying to split yourself in half." Go ahead and work full-time as an engineer. For now, be content to teach at your church on a spare-time, volunteer basis; don't think of this as a way to earn your living, but as a way to continue to explore your other vocational possibility. In the meantime, save up as much money as possible from your engineering job, in case you do eventually decide to change careers. At the end of your letter you gave me wide-open permission to advise you about other matters. I'll take it. I advise you in the strongest possible terms to stand up straight and take care of your family yourself. Don't expect your widowed mother to use up her savings to take care of you. She raised you, taught you, and put you through school; now you're a married man and a graduate, and it's your turn. At this stage, in your life and in hers, you should be thinking about how you can support her, not how she can support you. One more thing: Go help your wife with the dishes. You write as though giving her a few minutes of your time would have wrecked your whole evening of study and upset the division of labor. Nonsense. It's fine that she's the housewife and you're the engineer, but she's helping you bear your burdens, and you need to help her bear hers. If you want to quote Ephesians 5 to me, go to it, but start with the 21st verse.

|

Where the Action IsSaturday, 10-17-2015

Aristotle’s question endures: Which is better, the active or the contemplative life? The one wrapped up in doing things, or the one absorbed in gazing on the truth? Recently, when a few of my students brought up the question, I reflected on an epigram of Bernard of Clairvaux of which I am very fond, “Some seek knowledge for the sake of knowledge: that is curiosity. Others seek knowledge that they may themselves be known: that is vanity. But there are still others who seek knowledge in order to serve and edify others, and that is charity.” It may seem that someone who speaks like Bernard is siding for practical activity against contemplation, viewing knowledge as intrinsically worthless -- good only as a means to serving others. This view can’t be right, for unless it were good in itself, how could it serve them? Besides, Bernard is a contemplative: The author of the epigram is a man who has given his life to the contemplation of God, who is identical with Truth. Here is the solution to the riddle. Aristotle’s God is a solitary monad, “thought thinking itself.” Bernard’s is a burning unity of three Persons, their love His very being. The God whom Aristotle admires has no reason to be interested in us. The God whom Bernard adores made us in His image, woos us like a bridegroom, and suffered for us before all worlds. It follows that the action of charity is not in competition with the contemplative life, but at its heart. To contemplate God is to know Him not just as the theorem is known by the demonstrator, but as the Lover is known by the Beloved.

|

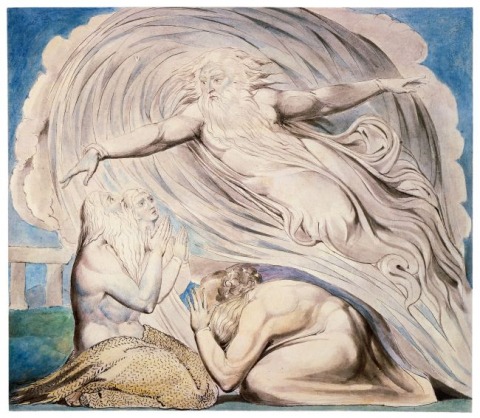

The Right Way to Get Angry with GodThursday, 10-15-2015

Speaking in San Marcos Thursday, Oct 15 Although Job was angry about his undeserved sufferings, Job didn’t go away and sulk; he gave God an earful. It’s plain from the text that he trusted God to judge justly if only He gave Job a hearing; He thought God wasn’t paying attention. God is always paying attention. In failing to realize that, Job erred, but he cannot be said to have lacked faith in God’s justice. Therefore, although God chides Job’s presumption, He approves his frankness. He tells Job’s accusing friends, who thought they were sticking up for God, that His anger blazes against them, “for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.” In a magnificently understated line, He tells them that He will forgive them, but not until Job – Job, the complainer! -- has prayed for them.

|

The Biggest Difference Between the Two PartiesWednesday, 10-14-2015

Speaking in San Marcos, Thursday, Oct 15 The biggest difference between the two parties is not that one tilts left and the other tilts right, but how their respective leaders play their hands. Democratic Party leadership plays up to its base, which responds, predictably, with loyalty. Republican Party leadership has contempt for its base, which responds, predictably, with resentment. The blame is not all on one side. Even resentful Democrats practice party discipline. Resentful Republicans wait until the ship is in sight of the port, then set it on fire.

|

Beating Up on St. AugustineMonday, 10-12-2015 |

For Him and Yet for OurselvesSunday, 10-11-2015

“But to a Being absolutely in need of nothing, no one of His works can contribute anything to His own use. Neither, again, did He make man for the sake of any of the other works which He has made. For nothing that is endowed with reason and judgment has been created, or is created, for the use of another, whether greater or less than itself, but for the sake of the life and continuance of the being itself so created .... “Therefore, ... it is quite clear that although, according to the first and more general view of the subject, God made man for Himself ... yet, according to the view which more nearly touches the beings created, He made him for the sake of the life of those created, .... For to creeping things, I suppose, and birds, and fishes, or, to speak more generally, all irrational creatures, God has assigned such a life as that; [but not] to those who bear upon them the image of the Creator Himself, and are endowed with understanding[.]” I am quoting from Athenagoras of Athens, On the Resurrection of the Dead, Chapter 12. Immanuel Kant wrongly gets credit for this insight because he wrote that we are always to be treated as ends, not as means. But even apart from the fact that he came sixteen centuries later than Athenagoras, Kant meant something quite different, and I think he was confused.

|

Hey, Kids! Now You Can Play the Slots Too!Friday, 10-09-2015

In my grandparents’ day, cigarettes were sold to children. By my day that was mostly a thing of the past, but I am old enough to remember how groceries and other merchants used to hawk candy cigarettes to children in the check-out lines. Think of sugary little Camels, Marlboroughs, and Lucky Strikes. What’s the big deal? They were only candy, right? Right, but the purpose was to generate future cigarette users. For the grocery stores, and for the tobacco companies which allowed candy manufacturers to use their trademarks, it was an investment. Eventually public opinion turned against the sale of candy cigarettes, and most grocery stores stopped carrying them. But the stores have adapted. For example, the H.E.B. grocery store chain encourages children to play the lottery instead. Hey, kids! Now you can play the slots too! Children don’t actually use money; they use “buddy bucks” which their mommies and daddies get along with their grocery receipts. Think that makes it harmless? Think again: Like candy cigarettes, this too is an investment. H.E.B. and other merchants get kickbacks from the state for selling lottery tickets to adults. The more children they suck into the idea that throwing away money is wonderful fun, the more future customers they have for this racket. Maybe Mom and Dad haven’t thought of that. Count on it, the company executives have. I am not a Puritan. I don’t think it is a sin to place a little wager. This is not about placing a little wager. Perhaps it doesn’t bother many people any more that an amoral government colludes with greedy merchants to prey upon the poorest and most foolish adults of the community by encouraging them to throw away their money in games of chance which are rigged against them. But must they make it glamorous to children? For shame.

|