The Underground Thomist

Blog

SuspensionMonday, 07-10-2023

Recently, as we were visiting his church out of town, an acquaintance who works hard to bring in the sheaves greeted me and my wife with the friendly remark, "I like people who believe in something." I wondered: Do the people we casually describe as believing nothing literally believe nothing? Or do they believe something after all? The usual view is that regarding both particular beliefs and belief in general, a person either believes something, disbelieves it, or suspends judgment. I think this way of viewing the matter is too simple. Regarding belief, people act out commitment and belonging in at least four different ways. The first way is alethic commitment: Committing and belonging because of considered belief that a thing is true. The second is social commitment: Committing and belonging because of a sheer need to commit and belong, simply taking for granted that the thing must be true. The third is conformity: Acting in a way that simulates commitment and belonging, not disbelieving the thing, but never really considering whether it is true. The fourth is cynicism: Acting in a way that simulates commitment and belonging, even though believing the thing untrue, just because one has something to gain. For example, one may strike a religious pose among Christians, or an atheist pose among atheists, in order to “get along.” To some extent, these four categories bleed into each other and are confused with each other. Alethic belief bleeds into social belief, because we are social beings who cannot help but be influenced by each other. This is why it is more important to have the right peers than to attempt an impossible immunity to peer pressure. Social belief blends into conformity, because we are careless beings who often live half-asleep. This is why it is so important to inspect our thought processes, even at some risk of confusion. Conformity bleeds into cynicism, because we are intellectual beings who cannot remain in suspension between belief and disbelief. As William James wrote, the mind operates with the attitude, “better face the enemy than the eternal Void!” Even the so-called agnostic, who is says he “just doesn’t know” whether, for instance, Jesus is the Son of God, is practically committed to living either as though He is, or as though He isn’t. Every way of living is some way of living. In fact, universal doubt is impossible, because even when we doubt something, we doubt it for the sake of something we are less in doubt about. I doubt that the shiny substance in my hand is diamond, because I can scratch it with a piece of steel, and I am not in doubt about the fact that diamond is harder than steel. Since every doubt in P supposes confidence in Q, we can doubt anything in particular, but we cannot doubt everything at once. Besides, no one would cynically simulate belief in something he disbelieved, unless, for some reason, he thought his advantage lay in “getting along” – which is, in itself, a belief. Why doesn’t he doubt that belief? In this sense even unprincipled people have principles, but bad ones. Back to my priestly friend, who likes people who believe in something. I don’t think he really meant to imply with his remark a person could believe nothing at all. But he daily contends with the thoughtless common habit of allowing trivial and unreasonable beliefs to crowd out questions about things which are not only more important, but ultimately even more reasonable. For the care of souls, he was looking for solutions. Everyone believes in something, and whatever he believes, he believes it for the sake of something. The question is what.

|

Eight Minutes on Why Stoicism Won’t Make You HappyFriday, 07-07-2023

Hear me talking for eight minutes about Why Stoicism won't make you happy on the Catholic Culture Podcast. (Interviewer Thomas V. Mirus.)

|

Elites, Deplorables, and Political StyleMonday, 07-03-2023

Allow me to update a post I wrote in 2020 about Donald Trump and social class, because the topic is broader than Trump. Let me begin with what I said then. There is a lot to dislike about him. Mr. Trump was a sneerer, mocker, boaster, and person of bad character -- and he still is. But then-president Obama, and his then-vice president, Joe Biden, were are also sneerers, mockers, boasters, and persons of bad character. “Why is the reaction to them so different?” I asked. The political classes adored Mr. Obama, liked Mr. Biden just fine, and still put up with Biden despite his obvious dementia, corruption, and incompetence. By contrast, they despised Trump so intensely that they were willing to pull down the republic to get rid of him. The instrumentalities of justice were weaponized against him. Their entertainers openly made jokes about assassinating him. The war shows no sign of ending; new assaults are launched daily. Of course part of the difference in the reaction to these politicians is ideological. Biden, like Obama before him, does things the political classes love, like promoting abortion, removing rules that protect the consciences of medical workers, distributing patronage to industries the political classes like, and expanding the regulatory apparatus. By contrast, Trump appointed pro-life judges and did other things that they hate. But that explains only part of it. The political classes didn’t cast a hold-your-nose vote for Obama, or even for Biden; they didn’t put up with them despite their personality, vices, or bad manners. They admired them for these qualities. Biden has become embarrassing to them, but not because of his crudity. I suggested in 2020 that “it’s a class thing.” A certain kind of oafishness is considered lovable by the political classes, and not even recognized as oafish because it is their sort of oafishness. Another kind of oafishness is considered lovable by those whom they disdain. Obama was a smooth rich fellow who flattered the elites. Biden is a coarse rich fellow who sneers at the common people in the same breath as he boasts of his humble origins. The elites think this kind of talk is merely telling it like it is. Trump is a coarse rich fellow who flatters the common people. Since he sneers at the elites and adopts a popular tone in doing so, it enrages them. Though all of these rulers claim to look out for the “little guy,” the difference is that Obama and Biden styled themselves as their patrons, and viewed the “little guys” as their clients. Trump styles himself as their benefactor, and views them as his constituents. Some people react viscerally to one kind of oafishness, some to the other. Very little of the reaction is about the respective vices of these politicians, though much could be said about them. Most of it is about the respective styles of their vices. It is very hard to wipe the smear of class from the window of judgment to see clearly. So much I wrote then. But there is more to say, because the “class thing” is much bigger than Donald Trump. Let’s put it in context. The same people who used to love the Republican and despise the Democratic Party have now flipped, for the wealthy and professional classes used to be mostly Republicans; today they are mostly Democrats. The biggest change is that “old money” doesn’t count for much any more, because the power has shifted to new money, high-tech money. Progressivism, understood as the ideal of rule by managerial elites who “know better,” has doubled down. Contempt for the blue collar and middle white collar classes, otherwise known as the “deplorables,” has intensified. People can be arrested for peacefully complaining at school board meetings, or surveilled for being religious. Several facts have obscured the reversal in the parties’ roles. One is that although the Democratic Party is now the party of the privileged, it still positions itself rhetorically as the defender of the marginalized. This, despite the fact that the actual effect of its policies is to increase economic dependence rather than reduce it, establishing all sorts of classes and underclasses of governmental clients. The second is that it retains the support of the most powerful unions, although these are no longer trade or industrial unions. The baton has now shifted to public employee unions – who strive to make their employer still bigger, and whose officers fully accept the managerial ethos. There is no longer any place in the Democratic Party for the deplorables to go. However, the Republican Party bosses adhere to a milder version of the same progressive ideology that the Democrats accept. So the deplorables have no home there either. No wonder the deplorables are resentful. And no wonder so many of them still admire Mr. Trump. It’s not that they like thugs. But if they have to be ruled by them, they would rather be ruled by their own thugs.

|

What’s Happenin’ NowMonday, 06-26-2023

For your perusal, a compilation of the latest tidbits from the newspaper of what’s happenin’ now.Self: Actually, it is all about me. Reality: Thinking and saying it make it so. Truth: See Reality. Sex: Okay if it doesn’t hurt anyone. Never hurts anyone. Existence of God: Doesn’t matter anyway. Good: What I want. Evil, meaning 1: What I don’t want. Must not be done. Evil, meaning 2: What you don’t want. May be done for good. See Good. Rights: I get to do what I want. Duties: You have to let me do what I want. Wisdom: Knowing how to get what I want. Justice, meaning 1: Abolishing police. Justice, meaning 2: Punishing political opponents. Justice, meaning 3: See Duties. Privilege: What I should have and you shouldn’t. Equity: See Privilege. Violence: Mostly peaceful, when committed in my cause. Racism: Thinking every race should be treated the same. Voting Rights: What dead people have in elections. Promises: Meaningless words that sound meaningful. Commitment: Not being married. Love: Sexual desire. Family: Any group of people whatsoever. Matrimony: Any group of people whatsoever, but with sex. Children: Lifestyle additions, like flatscreen TVs. Day Care: The golden key to childhood development. Mothers: Ought to be working. Fathers: Are dispensable. Parents: Need supervision by villages. Boys: Ought to be more like girls. Girls: Better version of boys. Gender: Whatever I want you to call me. Women: Some have penises, some don’t. Men: See Women. Respect: Saying what I tell you to say. Affirmation: See Respect. Virtue: Signaling that you hold the currently approved opinions. Extremist: Someone not holding the currently approved opinions. Disruptive: See Extremist. Intolerant: See Disruptive. Artificial intelligence: Soon to be the only kind. See also:Newspeak DictionaryDoubleplusgood DucktalkersPolitics and Language, RevisitedOur (Non) Racist and (Non) Sexist ConstitutionSo Called Inclusive Language

|

“Why Can't a Woman Be More Like a Man?” IIMonday, 06-19-2023

Why can't a woman be more like a man? Men are so honest, so thoroughly square; Eternally noble, historically fair; Who, when you win, will always give your back a pat. Well, why can't a woman be like that?

Why does every one do what the others do? Can't a woman learn to use her head? Why do they do everything their mothers do? Why don't they grow up -- well, like their father instead? *

We associate the deplorable idea that women need to be more like men with male chauvinists like Professor Higgins, who sings this song in My Fair Lady. But the song is sung by women too – especially from women who compete in historically male fields. Consider the strange remarks of a female scientist in her letter challenging a newspaper’s interpretation of some research she had published on women in science. The Wall Street Journal had lauded her findings that that women who apply for grants, submit journal articles, and ask for recommendation letters do just as well as men, and that women who apply for tenure-track jobs have even greater success than men. Opining that “Women in Science Are Doing All Right,” WSJ considered this good news. The author whose findings were reported, however, replied in the Letters column that although all that was true, women are less proportionately likely to apply for tenure-track jobs in the sciences in the first place. She complained, “Some may conclude, ‘That’s their choice.’ But the literature says that the major reason women Ph.D.s don’t apply to tenure-track jobs is that they look ahead to the four or five years of postdocs required in many fields and the six-year deadline to amass a tenure dossier, compare it to their biological clocks ticking away, and instead choose industry, government or nontenure-track academic jobs. That is not ‘all right’ if we want our best and brightest, men or women, to be the ones running university research labs and educating the next generation of Ph.D.s.” Women, you have been warned. Accept your discipline. It isn’t all right for you to heed your biological clock. It isn’t all right for you to prefer a career that doesn’t foreclose the possibility of becoming a mother. Bright scientists are so much more important than bright mothers. Educating the next generation is so much more important than bringing it into being. The lady’s objection is to women thinking -- like women. Why can’t they be -- more like men? You didn’t think feminism was about respecting women, did you?

* “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?”, a.k.a. “A Hymn to Him,” music by Frederick Loewe, lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, My Fair Lady (1964). Related: “Why Can't a Woman Be More Like a Man?”

|

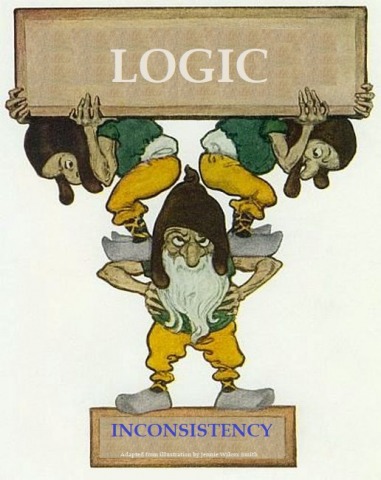

Is Inconsistency Really Just a Hobgoblin of Little Minds?Monday, 06-12-2023

In a previous post I commented on the attack on Aristotle’s Law of Excluded Middle – that a meaningful statement is either true or false, with no in-between. Today I’d like to comment on the related attack on his Law of Non-Contradiction, that no meaningful statement can be both true and false, in the same sense, at the same time. At stake is whether reality can be inconsistent. Some claim that the possibility of inconsistent realities is proven by Schrödinger’s cat. I am referring to a famous thought experiment in physics, in which a cat is locked in a box with a tiny bit of radioactive matter, along with a vial of poison gas, connected via a relay with a Geiger counter. If a radioactive nucleus decays, the vial of gas is shattered and the cat dies. If it doesn’t decay, no gas is released and the cat lives. The claim of the contradiction-mongers is that until the box is opened and the condition of the cat is observed, the cat is both dead and not dead. No: Until the box is opened and the condition of the cat is observed, we simply don’t know whether it is dead or not dead. True, the possibility that the cat is dead coexists with the possibility that it is not dead, but this in no way suggests that the dead cat coexists with the live cat. It turns out that this was Schrödinger’s own view too! Although the predictions of quantum theory have proven highly accurate, the notion that they show that the principle of non-contradiction can be violated is nonsense. Unfortunately, the more outré interpretations of what is going on with the cat receive more attention from science popularizers than the sensible interpretations do. If we understand truth as correspondence – if the thought expressed by the proposition “Snow is white” is true if, and only if, snow is white in reality – then it is difficult to imagine what anyone who says “Snow is white, and also snow is not white” thinks he is asserting. In fact, the statement that propositions can be both true and false would itself be both true and false. What is one to make of that? Moreover, it has been known for centuries that from a contradiction, literally anything can be shown to follow. For example, if snow is white, and also snow is not white, then it follows that God exists. And that fairies like ice cream. And that God doesn’t exist. And that fairies don’t eat at all. And that it isn’t true that snow is white. All possible inferences can be made. This calamitous result is sometimes called “explosion.” Given the principle of explosion, it would seem that whenever there is an inconsistency in a system of propositions, the game is up. But can we give up the game so easily? Sometimes, when we are dealing with enormous systems of propositions, we know that there are probably some inconsistencies in there – and we will try to get rid of them when we discover them – but in the meantime, we don’t know what they are. This being the case, it might be helpful to develop a way to insulate the rest of the system from so-far-undiscovered inconsistencies – to cautiously keep using the system while we are trying to find them and root them out. This is something like what computer programmers do when they try to develop programs that won’t crash every time, even though the programs inevitably still contain some bugs. Now some people who talk about such “paraconsistent” logics speak as though they thought a proposition really could be both true and false in the same sense at the same time – which requires believing that a thing can both be and not be in the same sense at the same time. This is called dialetheism, and to call it “badly confused” seems generous. But sometimes people who talk about paraconsistent logics speak more as though they are trying to develop coping strategies of the sort that I mentioned in computer programming. Their thought is merely that we may have to tolerate contradictions provisionally, while we are trying to find out what they are. This may not be insane, and may even be important -- although perhaps it is misleading to call the development of coping strategies “logic.” It might be more accurate to say that the goal is to protect logic from the illogic we haven’t yet caught.

Copyright © 2023 J. Budziszewski

|

Fuzzy Logic Is Fuzzy ThinkingSunday, 05-28-2023

Aristotle famously said that a meaningful statement is either true or false; there is no in-between. This is called the Law of Excluded Middle. However, a great many people say there can be in-betweens, and even try to axiomatize the idea. Sometimes this is called “fuzzy logic.” I think it’s fuzzy thinking. Superficially, the idea is plausible. After all, don’t we say that there are half-truths? We do say that, but only figuratively. The expression “half true” never means literally that a meaningful proposition can be something other than true or false, or that a state of affairs can be intermediate between reality and unreality. It may mean quite a number of other things, for example: 1. Someone might call the statement “Shale is a sedimentary rock” half true because he has only 50% confidence that it is true. Yet irrespective of how sure he is, the statement that shale is sedimentary is either true or false -- and irrespective of what kind of rock shale is, the statement that he has only 50% confidence about it being sedimentary is also either true or false. 2. Someone might call the statement “The cloth is white” half true because its actual shade is halfway between white and black. Yet what he means is that the cloth is gray, and the statement “The cloth is gray” is 100% true. 3. Someone might call the statement “Calico cats are even tempered” half true because the description applies to only half of all calico cats. Yet the more precise statement “Half of all calico cats are even tempered” would in this case be simply true. 4. Someone might call the statement “We have here a heap of sand” half true because the term “heap” is vague; there is no fixed number of grains above which an accumulation becomes unambiguously a heap. But by choosing to call a certain accumulation of sand a heap, he is using a noun as an oblique way to express a matter of degree – he is choosing to emphasize how much sand there is rather than how little. So saying “We have here a heap of sand” is like saying “Gee, what a lot,” or “There sure seems a lot of it to me.” And either there does seem a lot of it to me -- or there doesn’t. 5. Someone might claim that the statement "The unborn child is a person" is half true on grounds that the unborn child is only a potential person (in fact, this claim is rather common!). But although the unborn child has some unrealized potentialities – as a toddler does, or as the reader of this paragraph does – still, if the child weren’t already wholly a person, the child wouldn’t have these potentialities. A bone cell doesn't have such potentialities; a gamete doesn’t have them either. But from the moment the zygote comes into being, the zygote does. 6. Someone might claim that the statement “This theory is true” is half true because the theory consists of a number of different propositions, and not all of them are accurate. But taken one at a time, each of these propositions is either true or not. Rather than saying that the theory is half true, we should say something like “Half of its claims are true.” 7. Or take Objector 1’s statement, “Every intellect is false which understands a thing otherwise than as it is.” Someone might call it half true because it is true in one sense but false in another. But to say so is to admit that in each sense it is either true or false – not something in between. None of these possibilities shows that there are values of being between true and false. Moreover, each of these possibilities needs to be handled in its own way. Unfortunately, a system of inference which calls them all “half truths” treats them all the same. For as we see, ● Possibility (1) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that I may be more of less sure about what really is true. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should speak of degrees of confidence. ● Possibility (2) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some things are more or less. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should speak of degrees of qualities. ● Possibility (3) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some facts concern fractions or proportions. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should make use of our arithmetic. ● Possibility (4) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some ways of describing how much of something there is are indirect. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should pay closer attention to oblique modes of description. ● Possibility (5) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but that our grasp of personhood is defective. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should clean up our careless metaphysics. ● Possibility (6) is something like possibility (3). It doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that there are fractions. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should distinguish among the propositions in the theory. ● Possibility (7) doesn’t show that there are degrees of truth, but only that some statements are ambiguous. Instead of speaking of degrees of truth, we should say what we really mean. Other examples besides these seven can be suggested. For example, someone might call a proposition half true because it resembles the truth, because it figuratively expresses the truth, or because it could have been true, but isn’t. Someone might call a classification half true because an object is difficult to classify, because fits into more than one classification, or because no suitable classification for it has been devised. Someone might call the statement that Pegasus is a winged horse half true because Pegasus exists only in the story and not in reality. Someone might call the statement that a child is an adult half true because the child has traversed half of the distance toward being an adult. Someone might call the description of a patient as “still alive” half true because the patient is dying. And, of course, someone may call affirmations about God half true for all sorts of fuddled reasons. But in no cases whatsoever do we actually encounter states of being which are neither true nor false but something in between. So the figure of speech “half true” is merely an amusing, ambiguous shorthand for things that more clearly be said differently, and does not describe what is actually the case. The fact that we can devise formal systems of inference for so called half truths does not show that there are, in fact, states of affairs that are half so -- any more than the fact that we can formulate syllogisms about things that taste like the number seven shows there are, in fact, things that taste like the number seven.

Copyright © 2023 J. Budziszewski

|