The Underground Thomist

Blog

Robin Hood, RepriseMonday, 11-03-2025

Query from a reader Down Under:I’ve read your recent post Is Taxation Theft? When It Is and When It Isn’t (Monday, 09-08-2025). You suggest that although the government has its own proper work, this doesn’t include redistribution. This is a dividing line in our thinking, because I believe the government is good at many great things, including such as providing certain goods through redistributing wealth through taxation. Of course, this must be done according to law and not against constitutional limits, but the New Deal justices have answered that question pretty satisfactorily in my mind. Comments?

Reply:I agree that the government provides certain goods, but I don’t think it is “good” for government to provide something which someone else can provide better. For a single example – one with which I think you will agree – suppose the government took over all child care in the name of “helping families” and “relieving them of their burdens.” This would be dreadful. I am fond of the anecdote (it happens to be true, but I won’t name names) about two people running for office. One said, “No bureaucrat can love my children as much as I do.” The other, a social worker, said “That’s not true. I love your children just as much.” The former replied, “Tell me their names.” The government doesn’t do a good job of providing even those goods which it ought to provide. Among other things, government is wasteful, because bureaucracies like to enlarge themselves, and they have no incentive to keep costs down. Some economists suggest that whenever the government provides a good, the cost of providing it is about twice as much as when other parties provide it. This has come to be called the “rule of two.” I’m not certain whether your second paragraph means that whenever government taxes, in effect it redistributes wealth (which is of course true), or that redistribution of wealth as such is a good thing (with which I disagree). A difficulty lies in the ambiguity of the word “redistribution.” If by redistribution you mean simply helping those in need, I’m for it, although I think the most conspicuous efforts by government to help those in need have made them worse off rather than better. What the working poor need are jobs, not handouts which destroy their self-respect and encourage permanent multigenerational dependency. But if by redistribution you mean taking from those who have something just because they have it, and giving it to others just because they don’t, this is exactly what I criticized as the Robin Hood fallacy. It is theft, and yes, unfortunately the government is very good at it. We have a real moral duty to look for opportunities to help those in genuine need, but we should not confuse the needy with the merely wanty. There is no moral duty to make everyone the same, and it is not even a good idea, because it destroys initiative. Look what happened to the Soviet collective farms. People became more hungry, not less, because they received the same dole no matter how hard they worked. By the way, the data show that although progressives claim to be more compassionate, conservatives give a lot more to charity. What progressives mean by compassion isn’t that Paul helps out Sam, but that Peter puts his hand in Paul’s pocket and gives Sam what he finds there -- and the government is Peter. As to the justification of the administrative state by the courts of the New Deal, I applaud your desire to act only through law, but sometimes what the government calls a law can be in a deeper sense unlawful. The New Deal justices carved out a place for the administrative state by throwing out the “no redelegation of delegated powers” rule, which said that if one party delegates a power to another party, the second party must not turn around and give it to someone else. Formerly it had been held that since the people delegated the rulemaking power to the legislature, the legislature couldn’t redelegate it to executive agencies. That old understanding makes perfect sense to me. Moreover, it had always been held previously that the combination of all three kinds of power, legislative, executive, and judicial, in the same set of hands is “the very definition of tyranny” – those are the words of the great Constitutional architect James Madison. But executive agencies do combine all three kinds of power. They make rules, they execute rules, and they conduct their own judicial proceedings under the rules they draw up. You would like to believe in both a republic and an administrative state. I think you can believe in one or the other, but not both; you have to choose. Ultimately, the administrative state destroys the republic. It is the political tyranny of a single class, the class of experts, under the guise of not being political at all.

|

Undesired Desires?Monday, 10-27-2025

Query:If you don't mind, is it coherent for there to be such a thing as an "unwanted desire"? Or would that be an oxymoron? Someone might say that to desire not to desire P means nothing more than not desiring P -- but that seems wrong.

Reply:Yes, there can certainly be such a thing as an unwanted desire. Philosophers sometimes speak of “second order” desires, desires about desires. A person may desire to have a desire he does not have (God, help me to long for you more! Help me to will my unpleasant neighbor’s true good!). Or he may desire not to have a desire he does have (Father, help me not to have unchaste imaginations! Help me not to want to punch my rival in the nose!) One large part of the spiritual life lies in stirring up the desires we do desire to have. Another lies in dealing with desires we desire not to have. In dealing with unwanted desires, there are two extremes. At one extreme, a person may neglect to submit his desires to God for correction. At the other extreme, he may worry so much about their need for correction that his obsessive worry inflames the disorder. It is as though he thought, “I will not think about a hippopotamus! I won’t! I won’t! Oh, no, there is the thought again!”

|

The Abortion Pill and Mr. VanceMonday, 10-20-2025

Query from an overseas reader:I see that your FDA has recently approved a new, generic variety of the abortion pill. Some commentators say that under the law, the FDA couldn’t have done otherwise, while others say approval could have been blocked. An article in The Washington Examiner says this is the most anti-life Republican administration in history (though not as anti-life as the other party). What do you think of the fact that Vice President Vance seems to be on board with the decision? I ask as someone who is trying to navigate murky waters in my own country.

Reply:I wouldn’t go so far as to say that this is the most anti-life Republican administration in history. After all, during his first term Mr. Trump nominated the Supreme Court justices who provided the majority to overturn Roe v. Wade. But it is getting there. The FDA’s decision is a betrayal. Most abortions are now carried out by means of abortion pills. Since they are sold across state lines, to say that the overturning of Roe “returned the issue to the states” is grossly misleading. And yes, the agency could have done otherwise. As the article you mention points out, the FDA began a new safety review of the drug in September. It could have delayed its decision until the review was complete, but it didn’t. This is deeply disturbing. A new analysis of insurance data finds that more than one in ten of the women who take the abortion pill experience sepsis, infection, hemorrhaging, or another “serious adverse event.” The only reason regulators tolerate such a high level of danger to the mother is that the ability to kill her baby cheaply and conveniently trumps all considerations. In the meantime, the administration promotes in vitro fertilization, which produces large numbers of unwanted embryonic children and then destroys all but those few which are implanted. What does Mr. Vance think of all this? Consider five possibilities, ranked not in order of probability but from worst to best. (a) Perhaps he thinks these things are a good thing in principle. (b) Perhaps he thinks they are bad things, but doesn’t care enough to do anything about them. (c) Perhaps he opposes them, but thinks it isn’t yet feasible to ban them, because doing so would cause a backlash which would ensure the victory of politicians who actually promote abortion. (d) Perhaps he opposes them, but is biding his time, because as the evidence of their harm continues to roll in, banning them might soon become feasible. (e) Perhaps he opposes them, but since he serves a president who doesn’t think it is feasible to ban them, he is working behind the scenes to persuade him. In charity, I don’t believe his thinking is like (a). I hope his thinking isn’t like (b), although such attitudes do typify faux pro-lifers. I don’t understand how the president thinks, but in speaking to life advocates, Mr. Trump himself has made a few remarks suggestive of (c), and it is possible that Mr. Vance agrees. Ideally, Mr. Vance would be thinking along the lines of (d) or (e), though if he were, it is unlikely that he would tell us, because blabbing to the rest of us might doom his efforts to change his boss’s mind. I hope his bishop and confessor are speaking earnestly to him.

|

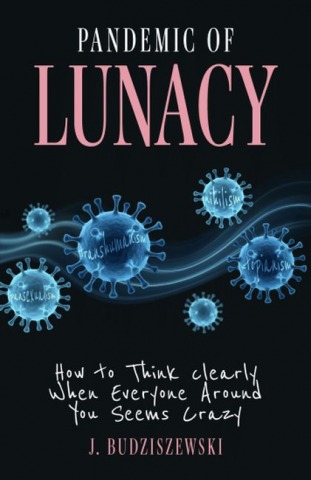

Pandemic of Lunacy available for pre-order!Thursday, 10-16-2025

I am delighted to announce that my new book Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy is now available for pre-order from Creed & Culture. If you Subscribe to the Creed & Culture mailing list, you can get a special 30% discount code. Here’s the description: ____________________ What is happening to the world? Why does it seem like everyone has gone crazy? Why are so many things that seemingly everyone believed the day before yesterday suddenly held to be retrograde, hateful, or even criminal? And why are things that everyone seemed to view as lunacy the day before yesterday suddenly taught or even required? In Pandemic of Lunacy: How to Think Clearly When Everyone Around You Seems Crazy, University of Texas philosopher J. Budziszewski patiently explains the delusions that beset us. Pandemic of Lunacy will be treasured by anyone who is troubled or confused, anyone who wonders whether the world has gone crazy or whether they have, and anyone who feels the need for a trustworthy guide in a topsy-turvy age. "Pandemic of Lunacy is brilliant, the corrective we need to pull the nation back from the abyss of unreason. Too many elites and intellectuals are saturated with ideologized education that has left them withering in a drought of real knowledge and common sense. Caring guides like J. Budziszewski might bring the best of them back from the realm of false light." — Dean Koontz, bestselling author “This book is simply the most complete, clear, and uncompromising account of our decaying culture's insanity that I have read yet.” — Peter Kreeft, professor of philosophy, Boston College “Philosophy and science go deeper than what common sense tells us, and sometimes correct it around the edges. But as thinkers like Aristotle and Aquinas knew, sound philosophy and science cannot coherently reject common sense altogether, especially in what it tells us about everyday human life. Modern thought has been plagued by one assault on common sense after another, typically grounded in simple but persistent fallacies. We need books that expose these fallacies and come to the defense of common sense. J. Budziszewski provides exactly that.” — Edward Feser, author, Five Proofs of the Existence of God J. Budziszewski offers both a subtle and wide-ranging exposition of the various individual lunacies that make up our corporate social insanity. His is a sober and shrewd voice that offers answers to our malaise. This is a profoundly helpful book for those wanting clarity in our deeply chaotic times.— Carl Trueman, author, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self J. Budziszewski is a professor of government and philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin. Internationally recognized for his work on natural law, self-deception, happiness, and ultimate purpose, he is widely read on the unraveling and possible restoration of our common culture. Among his twenty previous books are What We Can’t Not Know, How to Stay Christian in College, How and How Not to Be Happy, On the Meaning of Sex, The Line Through the Heart, The Revenge of Conscience, and a series of line-by-line commentaries on Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae. Married for more than five decades, a teacher for more than four, Budziszewski has two grown children and a clutch of grandchildren. His website, The Underground Thomist, is at undergroundthomist.org. Professor Budziszewski lives in Austin, Texas.

|

Nullification Again? No. This Is Worse.Monday, 10-13-2025

A number of conservative writers have criticized so-called sanctuary cities for – they say -- resurrecting the old “nullification” doctrine which over the years has been used to justify a variety of things, including the rebellion of the South in the Civil War. I agree that the rebellion was bad, and I agree that the sanctuary cities haven’t a leg to stand on. But it would be more accurate to say that the sanctuary cities want to resurrect anarchy than that they want to resurrect nullification. Nullification doctrine is different, and it is more subtle than it looks. What is nullification, anyway? During the first few decades of the republic, a lot of intelligent people were concerned that the federal government would become a tyrant, aggrandizing itself at the expense of the states. We have checks and balances inside the federal government; proponents of nullification wanted the states to have a check against the federal government, for our government is a “United States” rather than a single state. This is not a bad idea in itself. The argument for the nullification power is intriguing. We can put it in question-and-answer form.

From this, they concluded that a state may invalidate a federal law which it deemed unconstitutional, refusing to allow it to be enforced within the state’s territory. This was usually called nullification, sometimes interposition. I will explain in a few moments why their conclusion doesn’t follow, but first let’s take a step back and look at the problem from another angle. George Washington thought the invalidation of federal laws by individual states was a dreadful idea because it would "dissolve the union or produce coercion.” He and many others thought not just that federal laws are supreme within their proper sphere (which the Constitution affirms), but also that the federal government should have sole authority to determine the constitutionality of its own laws. But some of the other Founders of the republic thought allowing the federal government the authority to determine the constitutionality of its own laws would be like letting the fox guard the henhouse. In 1798, alarmed by the Alien and Sedition Acts, both Thomas Jefferson, in Kentucky, and James Madison, in Virginia, penned resolutions declaring that individual states had the authority to declare a federal law unconstitutional and refuse to allow its enforcement in their respective territories. Jefferson and Madison were right to oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts, which among other things violated the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech and press by declaring punishments for “false, scandalous, and malicious” criticisms of the government. Guess who would decide what counted as false, scandalous, or malicious? The government itself. Sound familiar? On the other hand, George Washington was right to think that Jefferson and Madison’s remedy went much, much too far, because it would pose the federal government with a terrible dilemma. The government could either use force to compel dissenting states to obey – or else it consent to its own dissolution. An excellent case can be made that the states ought to have some kind of constitutional check on an overbearing federal government. But consider: The constitution did not become a constitution just in those states which ratified it. Once it had two-thirds approval – nine of the original thirteen -- it became the constitution of all of them. So what we should conclude from the five bullet points isn’t that any state, all by itself, should be able to decide whether federal law is really law within its territory. It would make more sense to say that a two-thirds majority of the states could do so. In 1987, precisely this suggestion was made by former New Hampshire governor John Sununu. It would require a Constitutional amendment. So called sanctuary cities do not claim the measured sort of nullification power which Mr. Sununu suggested. They don’t even claim the more extreme version of the nullification power which Jefferson and Madison proposed. What they claim is that not just any state, but any locality may invalidate federal laws within its territory. This isn’t about the form of the federal union. It is a rejection of federal union. Even leaving aside the threat of lawlessness and chaos, by what possible constitutional theory could cities, not states, claim such power? The nullification theory bases its claim on the role the states had in ratifying the Constitution. But cities had no share in that at all. So the critics are right to repudiate the claims of the sanctuary cities, but their arguments need some tweaking. What the sanctuary cities propose isn’t your great-great-great-great grandmother’s version of nullification. It is something much different, and much worse.

|

How Can I Think About the Assassination?Monday, 10-06-2025

Query:Doubtlessly you’ve received other emails already since the events that took place around Charlie Kirk’s assassination, but I know no other place to ask for guidance so I must ask. In your living memory, has the United States political climate after World War II ever been this bad? It is exceedingly difficult to approach these events and retain the Christian morality that I know that I should exercise. I don’t know how people actually in the heat of the situation will be able to make the right choices, and mainly I’m worried for what comes after. Perhaps I am asking you to help me think. A more useful question might be to ask you what questions you’re asking yourself at this time, so I can think for myself.

Reply:The United States political climate has never been this bad in my memory. It isn’t that we haven’t passed through other periods of politically motivated violence in earlier years, but it was much more widely condemned. For elected officials and news commentators to have egged the violence on, as they do today, was unheard of. Even during the Vietnam War controversies, very few students, even on the radical left, sympathized with the terror bombings carried out by the SDS splinter group Weather Underground. The biggest confusion among my own students used to be rudderless moral relativism. Although there is still a lot of that, it seems to be on the decline. Now the problem is the explicit embrace of evil. The suggestion that one must never do what is intrinsically evil for the sake of a good result is a hard sell. Many of students are strongly attracted to “consequentialism,” the view that whether an act is right or wrong is determined only by the result. To say that the ends do not justify the means puzzles them. The decline of faith has also produced changes in character. Young people who were raised in Christian homes, but then abandoned Christianity, often used to retain vestiges of their moral upbringing, and accepted such ideas as courtesy, love of neighbor, and the sacredness of innocent human life. Today, having grown up in faithless homes, many seem to think that courtesy is for fools, that no one with whom they disagree is their neighbor, and that they should hate those they consider wrong instead of praying for their repentance and restoration. As for the sacredness of innocent human life – for them, that idea went out when they embraced abortion. However, I see some good signs. There is always “wrong on both sides,” but it isn’t equal. On one side, the violent nuts are merely the fringe. On the other side, they are the majority. I notice, too, that the former side is still having children. Charlie Kirk himself strongly encouraged young people to marry, have children, and hope for the future. Marrying and having children itself changes us, shattering our selfishness, forcing us to live sacrificially for others. He also spoke openly about God. I don’t think we can reform ourselves by our own powers, just by trying hard. I know by experience that God can change us, and I find an increased longing for the truth and grace of God among many of my students. They have had enough, and “having enough” doesn’t meant that they start shooting, but that they start inquiring about Him. May He grant that I help that along! If I believed the strange things so many people believe today, then I would be without hope. Seeing all the downward trend lines, I would despair. But I don’t believe that way, and trendlines are not a fate. In the first place, the providence of the loving God overrules our designs. In the second place, His grace through Jesus Christ enables us not only to repent, turn around, be forgiven, and forgive, but also be healed by a power greater than any mere resolution to be good. As C.S. Lewis pointed out, a culture does not last forever, but a soul does. The redeemed will still be glowing when the last star has died out. Sneering at people of faith, some people say “History is against you.” By history, though, they mean only the last 15 minutes -- and they don’t understand even those. For me, as you may know, this deeply personal. When I first got my PhD, I thought that good and evil were arbitrary human inventions, and that we are not responsible for our actions anyway. It took some years of painful divine surgery, but now I know better. When I hear people around me saying crazy things, I remind myself that I used say many of them myself. God, blessed be He, has devised a suitable penance for me, and I pray that I will never forget it. So as to your second query, about what questions I may be asking yourself at this time: I don’t spend much time asking what is going to happen, but I do ask what God would like me to do in my own place. He sees the whole shape of things. I can’t, but like a faithful bone, I can try to turn nimbly in the joint where I’m placed. Write any time.

|

Those Violent Other PeopleMonday, 09-29-2025

Recently I read a news story purporting to give the results of a statistical study of the politically motivated violence in recent generations. I am resisting the temptation to comment on the timing. The upshot was that for several generations, the great majority of instances of politically motivated violence were motivated by right-wing or conservative ideologies, with incidents of left-wing violence becoming a majority only in the last few years. Such exercises in counting on fingers are worthless. Terms like “right” and “left” have some usefulness in limited contexts in which all sides use the terms the same way. The problem is that since they have no universally agreed-upon definitions, it is far too easy to manipulate them. During the Jim Crow years, segregationists were part of the New Deal alliance, which might reasonably be viewed as making them part of the left. They engaged in plenty of violence. But we are required to call them conservatives because, after all, they were segregationists. Segregation was bad and old, and everything bad and old is conservative, don’t you know? By most definitions, communists are part of the left, not the right. But the die-hard communists who resisted the breakup of communism in the Soviet Union were called conservatives because they wanted to conserve – well, communism. Monarchists are called right-wing, and Stalinists are called left-wing. Yet what was Stalin but a tyrannical monarch by another name? Socialists are considered part of the left, and Adolph Hitler’s party were called National Socialists – Nazis, for short -- because they accepted the tenets of revolutionary socialism, but rejected the internationalism of other socialists. Although they wanted to smash institutions, not conserve them, today we unhesitatingly classify them as conservatives -- because, golly, they were extreme racists, so they just had to be conservatives. The ideology of Italian Fascism was a totalitarian confection made up of nationalism mixed with what most of us would call left-wing ideologies such as socialism, anarchism, and syndicalism. But we call it right-wing, because, after all, it was a new kind of leftism, which broke with the old kind. Surveying this terminological chaos, we misunderstand our own confusion, saying “Isn’t it amazing that the extreme right is so much like the extreme left!” But in many cases, so called extreme right-wingers are varieties of what used to be called extreme left-wingers. We’ve merely changed the definitions.

|