The Underground Thomist

Blog

Against “Natural Ingredients”Monday, 08-04-2025

By “natural ingredients,” people mean ingredients derived from nature. But every ingredient is derived from nature. Snake venom is derived from nature. Arsenic is derived from nature. It would be an exaggeration to say that you can derive anything from anything, but if you apply enough processing to ordinary proteins and carbohydrates, you can derive all sorts of noxious substances. To get poisons, you don’t have to start with poisons. The term “natural ingredients” would be meaningful and helpful only if it were used to mean ingredients which beings of our nature can consume safely. If we don’t use it that way (and we don’t), then we might as well get rid of it. So in case the title of this post confused you, I’m completely on board with natural ingredients. I oppose only “natural ingredients.”

|

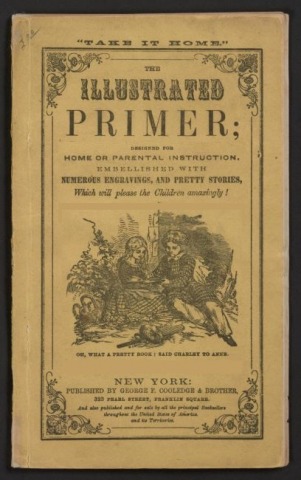

A Primer on ProgressivismMonday, 07-28-2025

Like many people, I was taught in school that the early progressive movement, from which today's progressivism descends, was a movement of reform against political corruption. Its proponents opposed urban political “machines” because they wanted to “take the politics out of government” and make it “clean.” For example, instead of cronyism and patronage, they wanted a nonpartisan civil service. The rule of experts would replace the rule of corrupt ward bosses – and the power of the government would be increased so that it could to do more good. Although these words corresponded to the progressive self-description, they are misleading. Progressivism wasn’t against class government, as you might think; it was all about class government. The supporters of the machines were mostly recent immigrants and working-class folk, but the experts represented the views of the professional class, who have now morphed into technocrats. They were highly political in their own way, but had different political ideas, and their supposedly neutral administrative state invented its own forms of cronyism, patronage, and corruption. Under progressive rule, the power of the central government is wielded largely to do harm in the name of good. Progressives want progress, but to measure progress one would need a fixed standard, and progressives reject fixed standards. The dominant philosophy of the progressive movement was, and is, what is called pragmatism, the glittery philosophy that truth is “whatever works.” Since the definition of “works” is up for grabs, this has come to mean that truth is “whatever I have to say to bring about what people like me want to happen – and to retain the power to go on making it happen.” In courts, this approach is sometimes called “results-based jurisprudence,” which is not really jurisprudence at all. It is not an attempt to follow the law, but a redefinition of law as whatever we want people to follow. Instead of being an instrument of fairness and predictability, as it ought to be, due process becomes a continuation of political war by other means – a wax nose to be twisted in the shape of the outcome the progressive desires. To progressives, such tactics don’t seem cynical, because in their view, the idea that law has a meaning independent of what one desires is a naïve mystification. Since law can’t speak for itself, you see, jurists can’t be interpreters, and have to be ventriloquists instead. Even knowing these things, some things about progressivism are surprising. For example, when progressive elites are caught making obviously terrible policies, as with open borders, they don’t change them – they dig in. Why? In the case of open borders, part of the reason is that the purpose never was to make good policy. Open borders were supposed to bring in a trove of voters who were vulnerable enough to be manipulated. That turns out to be another aspect of “what works” -- although in fact, it hasn’t worked even on its own terms. First-generation citizens tend to be no fonder of open borders than their fellow citizens are. But another reason is symbolic. Every defeat on a major policy discredits the rule of experts, and threatens to bring the regime into question. It is not a nice position to be in. Even when wrong, one has to be right. Related:What Kind of Progress Does Progressivism Want?Come on, Man! The President as an Ethical Theorist

|

The Abolition of WomanMonday, 07-21-2025

Men and women bear equal dignity as human beings. But the men-in-women's-sports scandal is an elegant demonstration that the claim that men and women are just the same in doesn’t liberate women, but subjugates and abolishes them. One could almost be grateful for the travesty of those men pretending to be women, because for those who have eyes to see, it makes the point clear.

|

Complimenting Women (Without Treading on Mines)Monday, 07-14-2025

Query from a reader in South Asia:Recently I complimented a female friend who was wearing a Western style crop top which I found attractive. I am wondering if my compliment was appropriate. One reason for wondering is that today crop tops for females are viewed as within the bounds of decency, although this may have not been the case fifty years ago.

Reply:I think your question unpacks into three questions. One wouldn’t want to obsess over them, but it’s interesting to give them some thought -- not just because you are wondering whether your compliment was polite, but because your problem concerns the relationship of changing to unchanging things. Whenever I teach about natural law, I find that people have a hard time with the idea that the application of a fixed standard is not necessarily fixed itself. They tend to think either that the applications can’t change, or else, that if they can, there just aren’t any underlying standards. Besides, decency is a slippery topic. Needless to say, so is avoiding offense. The first question. Can standards of decency in clothing change over time? Sure. Needless to say, one should never wear clothing just to excite thoughts of sex. Unfortunately, today many young women are encouraged to attract male attention not by being pretty, but by dressing in such a way as to arouse prurience, and quite a few men and women no longer understand the difference. But what does count as sexually provocative? At one period in my country, for a woman to show any part of her legs above her ankles would have been considered indecent. Somewhat later, it was considered “daring,” but not quite indecent. Today, the sight of some portion of leg is so common that no one gives a thought to a glimpse of leg. Since it is no longer particularly provocative, it has become decent. The second question. Can such standards vary geographically? Of course. In some countries, clothing which exposes a woman’s midriff is considered attractive but not provocative; in others, it is considered quite indecent. I grew up in an era when a woman of my country would never have considered showing her navel in everyday wear, and I am still uncomfortable with this style of dress. However, my feelings are not the measure of all things. Moreover, I would certainly not view it as pushing the boundaries of decency to dress in this way in a country in which it was customary, and I realize that the historical standards concerning the midriff are different in your country and in mine. Of course there are all sorts of ways to show the midriff, and many degrees of exposure. In a given place and time, one style of doing so may cross the line, but another may not. The final question. May one compliment a woman’s appearance? Well, yes, but such norms too vary across time and place. In my country these days, complimenting a woman’s appearance is like walking across a minefield, because it risks the presumption of prurient or even predatory intent. That may not be the case in yours. Depending on one’s culture, whether a compliment is considered appropriate also depends on who is complimenting whom -- on the nature of the relationship between them -- on their respective states of life -- on whether the compliment concerns the clothing, an accessory, or the body as expressed by the clothing -- on the part of the body which the clothing or accessory covers, suggests, or reveals -- on whether the compliment implies comparison between the charms of the person complimented and the charms of others -- on whether it is offered in public or in private, or in a formal or informal context – on whether one meets or avoids the eyes of the person complimented -- and on all sorts of other matters bearing on the inference of intent, such as voice tone and facial expression. You wouldn’t want to leer, for instance. Maintaining the presumption of innocence becomes nearly impossible in a hypersexualized culture. At the present day, in my own country, whether a compliment is welcomed or rejected may even depend on the political views of the person who receives it! Now doesn’t all that make everything easy? P.S. For less about what does change, and more about what doesn’t, I think you would be interested in the chapter on “The Meaning of Sexual Beauty” in my book On the Meaning of Sex.

|

Does Beauty Have Survival Value?Monday, 07-07-2025

Query:C.S. Lewis said, "Friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself (for God did not need to create). It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival." This prompts me to ask you whether you believe beauty is "necessary" for life. I am thinking that it’s technically not essential for survival, but still key to a good life. Would you share your thoughts on this?

Reply:I do think beauty is necessary for life, but to make my meaning clear, I had better make a few distinctions. Sometimes when we say that having P is “necessary” for doing Q, we mean that we can’t do Q as well without P. This is how we are speaking when we say that an automobile is “necessary” for getting to San Antonio. Sure, we could walk there, but it would be slow and difficult. Is beauty necessary for life in this sense? Yes. God has endowed us with such a powerful longing for beauty that if we are drowning in ugliness, we will probably be sad and listless even if we do stay alive. We will not be living well. On the other hand, sometimes when we say that having P is “necessary” for doing Q, we mean that we can’t do Q at all without P. This is how we are speaking when we say that lungs are “necessary” for breathing. Remove my lungs, and I die. Is beauty necessary for life in that sense? Probably not – yet in some cases it can be. One can imagine a person who has no beauty whatsoever in his life, who finally becomes so listless that he stops eating and taking care of himself, so that he does die. Your introduction of the expression “survival value” brings in another complication, though, because this expression too can be taken in two senses. A person who asks whether beauty has “survival value” may mean, “Given that we are creatures who powerfully long for beauty, will we die without it?” I’ve just answered that question above. We probably won’t die without it, but we might. But a person who asks whether beauty has “survival value” might instead mean something quite different. He might be asking, “Can I explain the human longing for beauty in terms of adaptation, as Darwin would have explained it? That is, would a creature which did long for beauty have a better shot at passing on its genes than a creature which didn’t long for it?” And to that question, the answer is plainly “No.” Consider a creature which desires only food, water, shelter, and a mate. If it can get these things, it not only survives but thrives, and if it doesn’t get them, it dies. Now consider a creature which not only desires food, water, shelter, and a mate, but also longs for beauty. The conditions for its flourishing aren’t easier to achieve, but harder, because even if it does have the other four things, it still may not have beauty. For this reason, one would expect a mere process of natural selection to work against the development of a general longing for beauty. Yet here we are. From a sheer biological perspective, this looks like a miracle. The suggestion that creatures like us are merely the meaningless and purposeless result of a process which did not have us in mind is staggeringly implausible.

|

Elon Musk, Babies, and TapewormsWednesday, 07-02-2025

Elon Musk has many children with many women, some of them paid very large sums to bear them. He says his purpose is to help stave off population decline due to falling birthrates. A more likely motive is to multiply his own image. It is a technological solution to depopulation, like a photocopying machine: There aren't enough children, so get lots of women pregnant. Needless to say, this is not kind to the children. Human children need a mom and a dad, not a mom and a rich sperm donor. The moral solution to depopulation would be to marry, have lots of children with one's wife, and encourage others to do likewise. Earth's creatures have two ways to continue the species. Some, like tapeworms, have huge numbers of offspring but invest little or no time in any of them. Most of the offspring die, but a small percentage of a huge number is still something. If only Mr. Musk would think less like a tapeworm and more like a human being.

|

Rules-Based International OrderSaturday, 06-21-2025

Why do we keep finding ourselves at war? Why can’t all nations agree to a rules-based international order? The reason is that what the foreign policy establishment likes to call “rules-based international order” is something like a constitution without a government. Since there is no overall authority to enforce the rules, the system gives the advantage to rogues, who exploit the reluctance of rule-following states to act against them. Of course, even without an overall authority, likeminded states can act together to punish violations of the rules. But reaching agreement to do so is difficult, and the difficulty goes beyond merely getting them to agree. For how do you do away with the temptation to be a free rider? If some states agree to enact sanctions, then other states will use the opportunity to cut a deal with the rogue. In fact, even states which approve the sanctions in principle will be tempted to work around them quietly. Besides, the goal of those who cherish the idea of a rules-based international order is predictability. Everyone knows what everyone else will and won’t do under every condition. So those who aren’t pleased with the status quo game the system, always walking right up to the line and putting their toes a quarter of an inch beyond it. The temptation of the status quo states is to keep moving the line back. Thus, without occasional resort to force, the so-called rules-based international order makes certain disruptions of international order more likely rather than less. And that means less peace rather than more.

|