The Underground Thomist

Blog

What the Pundits Missed about Senator KaineMonday, 09-22-2025

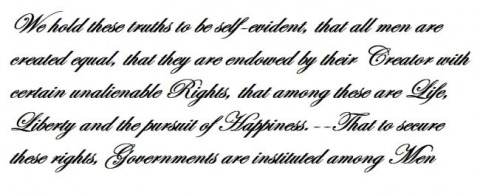

During the past few weeks, a great many pundits have commented on Democratic Senator Tim Kaine’s bizarre remarks in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on September 4th, but although most of his critics make good points, they are missing one of the most important. Kaine was criticizing Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who had pointed out that our republic was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that our rights come not from laws or governments, but from God. Secretary Rubio wasn’t pulling the idea from a hat. It comes straight from the Declaration of Independence. Government ought to protect our natural rights, but we have them whether the government recognizes them or not, because they come from a higher source than government. God built them into our nature. Thus, we are beings of such a nature that some things cannot be done to us without grave wrong. Here is how Sen. Kaine replied: “The notion that rights don't come from laws and don't come from the government, but come from the Creator — that's what the Iranian government believes. It's a theocratic regime that bases its rule on Shari’a law and targets Sunnis, Bahá'ís, Jews, Christians and other religious minorities. And they do it because they believe that they understand what natural rights are from their Creator. So the statement that our rights do not come from our laws or our governments is extremely troubling.” All of the critics get the first reason the senator’s remark was bizarre. He seemed completely ignorant of the fact that our own republic, which is no theocracy, was founded on the concept of natural rights which come from the Creator. To him, this founding principle is a brand-new idea which smacks of theocracy and Shari’a. Most of the critics also get the second reason the senator’s remark was bizarre, which is his explanation of it. The senator said that he believed in natural rights (in a sense he did not explain), but that “people … with different religious traditions” have “significant differences in the definitions of those natural rights." The tacit argument might be put like this:

This line of thinking is so obviously fallacious that one suspects there must be something more in the senator’s mind. I think there is. For the third reason Sen. Kaine’s remark was bizarre is one which even most critics have missed. The senator seems to confuse an ontological claim, that is, a claim about what we are, with a claim about identity, that is, a claim about which group we belong to. What the principle of natural rights claims is that we have rights because we are created in God’s image, whether our religion acknowledges this or not. Therefore the Christian, the Jew, the Muslim, the Bahá'í, and the atheist all have the same natural rights. This is the idea on which our republic was founded, and the senator is oblivious to it. But Sen. Kaine thinks that the principle means that we have rights because of our group, because of what our religion believes about God. Muslims, in his telling, think they get rights from “their” Creator only from believing their holy writings; Christians, that they get rights from “their” Creator only from believing their holy writings; and so on. So each group concludes that religious groups other than themselves don’t have these rights from God. Let us set aside whether this is an accurate description of what Muslims believe. It surely isn’t an accurate description of what Christians believe, and more to the point, it isn’t an accurate description of the principle of natural rights. In fact, what the senator calls natural rights aren’t natural. In his view there would seem to be Jewish rights as seen by Jews, Muslim rights as seen by Muslims, and Christian rights as seen by Christians, but there just aren’t any merely human rights, rights for all who share human nature. If we really do have rights because God made us that way, then they are discovered, not invented, and they preexist laws and governments. This fact lays on government a duty to make laws which identify, acknowledge, and protect them. The alternative is to think rights are arbitrary things that governments are free to invent, define, redefine, or wipe out of existence just as they please. They are just one more form of policy. And despite his claim to believe in natural rights, that is what the senator seems to think.

|

“He Must Be Crazy!”Monday, 09-15-2025

Query:Some people blur the distinction between mental illness and moral wrong by ascribing certain behaviors to mental illness when they are in fact simply evil acts. Have you ever addressed this interesting topic?

Reply:I haven’t written much about your question, but let me make amends. It’s a good one for sure. I was brought up to believe that all criminality and wrongdoing reflect a kind of mental disease, and we do say things like “The man who stabbed that woman on the subway must have been crazy!” and “What a nutcase, to shoot someone just because he disagrees!” If a stabber or the gunman were really nuts, we think, then he wouldn’t be to blame. Or would he? It’s true that all justifications for doing wrong reflect some sort of disordered thinking. But are they disordered in that sense? The traditional insanity defense tried to pin down the kind of disorder which absolves a person of blame, declaring that he would have to be incapable of telling the difference between right and wrong. Unfortunately, this standard doesn’t pin down what it is supposed to pin down, because the idea of not being able to tell the difference between right and wrong is deeply ambiguous. Let’s see whether we can untangle the matter by making some distinctions. What does it mean to say that someone can’t tell the difference between right and wrong? Suppose we take it to mean that a person understands all the words in a sentence like “It is wrong to deliberately take innocent human life” but just doesn’t know that the sentence is true. I don’t think this is possible: There are no such people. If this were what the insanity defense meant, it would be nonsensical. But there are other cases. First, here are two cases in which a person is clearly not culpable for wrong acts.

Now here are four cases in which a person should be viewed as culpable for wrong acts, even though some might deny it.

Finally, here are two cases in which a person may or may not be culpable, or may be culpable to a greater or lesser degree.

So most criminals are to blame. Only a few rare ones are not, but even they should be restrained, whether in a prison or a mental institution. People of a certain widespread persuasion think that because of the unequal distribution of wealth, no criminals are to blame. They suppose that crime isn’t due to sin, but to capitalism. For example, they make excuses for burglars because houses are so expensive these days. You can work out for yourself into which of the cases I’ve discussed these ideologues fall.

|

Is Taxation Theft? When It Is and When It Isn’tMonday, 09-08-2025

One of the great moral errors of our day might be called expropriationism. If you prefer catchier labels, call it the Robin Hood Fallacy. According to this notion, government is entitled to confiscate wealth for no other reason than “doing good.” This leads to a style of politics in which the groups in power decide for us which of their own causes our wealth is to support, taking it by force. Sometimes they even offer the pretense that they are helping the needy, but usually they confuse the needy with some subset of the merely wanty – or with their partisan clients, which is even worse. Many Christians seem to miss the point, thinking that expropriation is wrong just because the wrong groups are in power, choosing the wrong causes for subsidy. This is where the horror stories are offered, and horrible they are: Of subsidies to promote abortion, subsidies to produce obscene and blasphemous “art,” subsidies for all sorts of wickedness and blasphemy. But expropriation would be wrong even if each of its causes were good. Consider the following progression. 1. On a dark street, a man draws a knife and demands my money for drugs. 2. Instead of demanding my money for drugs, he demands it for the Church. 3. Instead of being alone, he is with a bishop of the Church who acts as bagman. 4. Instead of drawing a knife, he produces a policeman who says I must do as he says. 5. Instead of meeting me on the street, he mails me his demand as an official agent of the government. If the first is theft, it is difficult to see why the other four are not also theft. Expropriation is wrong not because its causes are wrong, but because it is a violation of the Commandment, Thou shalt not steal -- even if you think you can use the money better than your victim can. But how, one may ask, can government steal? We live in a republic; aren't we therefore just taking from ourselves? No, not even in a republic are the rulers identical with the ruled, nor for that matter are the ruled identical with each other; if we were just taking from ourselves, there would be no need for the taking to be enforced. Then is all taxation theft? A lot of people on both left and right think so -- anarcho-capitalists, anarcho-communists, libertarians, voluntarists, and others -- but no. Government may certainly collect taxes for the support of its proper work. The key is to identify its proper work. That work is not the support of all good causes or the doing of all good deeds, because each of the other forms of association in society has its own proper work, which ought not be taken away. Families have work that no one else can do. So do churches and synagogues. So do neighborhoods. So do protective associations for working people, farmers, and businessmen. I don’t say that such associations can never desecrate their own work, as when teachers enforce ideological purity instead of teaching, or lobby legislators to increase public education budgets which are already filled with lard. I only say that they have their own work. This establishes a strong presumption against most of the things into which government likes to stick its fingers. Let the other associations confine themselves to doing what only they can do. Let government confine itself to what only it can do, chiefly by upholding public justice. But if government were to end its subsidy of good causes, wouldn't these good causes suffer? Not necessarily; they might even thrive. As Marvin Olasky has shown in one of my favorite books, The Tragedy of American Compassion, government subsidy itself can make good causes suffer. One reason is that in taking money by force, one weakens both the means and the motive for people to give freely. Not only that, but government usually distorts good causes in the act of absorbing them. But what if the causes did depend on the proceeds of theft? Should we do evil, that good may come? There is no such thing as a tame injustice which will do only what we want it to, going quietly back into its bottle when we have finished with it. Sin is no more like that than holiness is. In politics, no less than in private life, it ramifies.

|

Laws of ThoughtMonday, 09-01-2025

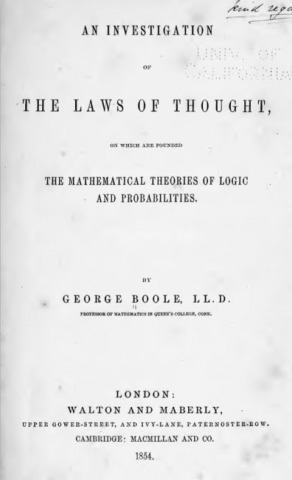

Today’s post concerns the nature of logic. It will bore some readers, interest others, and fascinate a few. Read on to find out which kind you are. Aristotle famously distinguished between theoretical syllogisms (which describe how we consider what is the case) and practical syllogisms (which describe how we decide what to do). Here is an example of a theoretical syllogism. The crucial thing is that the premises and the conclusion are all propositions: SYLLOGISM #1: All men are mortal. I am a man. Therefore, I am mortal. Here is an example of a practical syllogism. This time the crucial thing is that although the premises are propositions, the conclusion is not a proposition. It is an act, a decision: SYLLOGISM #2: Theft is wrong. Taking Steve’s wallet is theft. So I don’t take it. The reason the first syllogism ends in a proposition, but the second one ends in a decision, is that Aristotle viewed logic as the laws of rightly ordered thought. For much of its history, logic was always presented that way! Today, however, the topic is usually presented differently. Students today are taught to view it, not as the theory of rightly ordered thought, but as the theory of the consequence relation – something purely formal. Another way to put this is that Aristotle viewed logic almost as a branch of ethics, but today’s logicians view it almost as a branch of metaphysics. (The two, of course, are connected – at least from the classical point of view.) Reading Aristotle’s logic with contemporary assumptions easily leads to misunderstanding, because when today’s students are taught about Aristotle’s practical syllogisms, they usually think that their conclusions must be propositions – like this: SYLLOGISM #3: Theft is wrong. Taking Steve’s wallet is theft. Therefore, taking Steve’s wallet is wrong. Now “Taking Steve’s wallet is wrong” isn’t a decision that I make, but a conclusion about what is the case. I might ignore it – that is, I might acknowledge that taking his wallet is wrong, but take it anyway. Just for this reason, Aristotle himself would regard Syllogism #3 not as a practical syllogism, but as a theoretical syllogism. Well, that’s fine. But even so, Syllogism #3 has something to do with practice, doesn’t it? For a rightly ordered mind reasons, “If taking Steve’s wallet is wrong, I won’t take it.” Calling Syllogism #3 a theoretical syllogism and letting it go at that misses that important point. For this reason, I think modern Aristotelians need a name for mental processes like Syllogism #3. We might call them not just theoretical, but practitheoretical syllogisms -- theoretical syllogisms, but with a twist. But just as there are syllogisms which Aristotle would call theoretical yet have something to do with practice, aren’t there also syllogisms which Aristotle would call practical yet have something to do with what is the case? Like this one: SYLLOGISM #4 All men are mortal. I am a man. So I concede my mortality. The reason Aristotle would call this a practical syllogism is that “I concede the fact of my mortality” isn’t a conclusion about what is the case (what is the case is up there in the premises), but a decision that I make. I might have refused assent to the fact of my mortality, but, having a rightly ordered mind, I assent to it. And again, that’s fine. But just as Syllogism #3, even though it is a theoretical syllogism, has something to do with practice, so Syllogism #4, even though it is a practical syllogism, has something to do with what is the case. It is all about whether I give in to what is the case. So, just as I think modern Aristotelians need a name for mental processes like Syllogism #3, so think that they need a name for mental processes like Syllogism #4. We might call them not just practical, but theoripractical syllogisms – practical syllogisms, but with a twist. Now if you take the contemporary view, thinking of logic as merely the theory of the consequence relation, then none of this will make a bit of difference to you. To you, Aristotle’s practical syllogisms aren’t syllogisms at all. Theoretical syllogisms are the only kind there are. But if you take the classical view, thinking of logic as the laws of rightly ordered thought, then these distinctions are important. They reflect four different ways in which a rightly ordered mind may approach matters, whether theoretical or practical. School over.

|

Misgendering and Other MissesMonday, 08-25-2025

In some states and countries, legislators have moved to criminalize misgendering – that is, calling people by their biological sexes instead of the sexes they say they are. What a blow for equality! But why stop there? Why do we stigmatize misgendering, and yet turn a blind eye to misspeciesing? After all, some folks claim to be cats, foxes, raccoons, and other animals. It insults them to be called human. I say, all of the bigots who call them people should be put in jail. Besides being right and just, calling folks by their true species would also save on the costs of raising kids. If little Jeffy identifies as a dog, he can be kept in a doghouse and fed kibble, and there is no need to send him to school. I can see this becoming very popular, especially among people who don’t like their children. And what about all the people who claim to be different people? If they say they are, then they are. That’s just science! From now on, anyone who says he is Donald Trump must be addressed as “Mr. President,” and anyone who says he is Jesus Christ must receive the prayers of the faithful. The pioneer of this movement for justice was Grace Slick, former singer with Jefferson Airplane, once called the Queen of Acid Rock. After Slick delivered a daughter -- excuse me, an offspring assigned the female sex at birth -- a Catholic nurse came around with a form, asking what name she had chosen for her. Slick replied, “god. We spell it with a small g because we want her to be humble.” Unfortunately, Slick didn’t have the courage of her convictions. Claiming she had been joking, she later said that her daughter should be called “China.” Poor little girl, to be relegated to such a wretched fate! For all her days to be called a mere country, when really she was the lord of the universe! These cruelties have got to be stopped. Everyone has a right to be affirmed in, well, whatever. No more putting it off. Do it now.

|

Mixed FeelingsMonday, 08-18-2025

I confess to having mixed feelings about the recent case in which the Court ruled that Oklahoma cannot deny charter status to a school just because it is Catholic. On the one hand, the decision is clearly correct. Certainly this sort of discrimination by the state on the basis of faith should not be allowed, provided that the faith accords with natural law. (I would certainly discriminate against a religion of assassination.) However, whether the Church is well-advised to take advantage of benefits such as those which charter schools receive is another question. Since money always has strings attached -- and the strings get shorter and stronger over time -- other ways must be found to make Catholic education available to those who desire it. Making it available is especially necessary in view of the degeneration of the public schools. Please let’s not blather about religious “neutrality.” So called secular education is not neutral, but reflects a bias against faith in favor of irreligion. In fact, even that way of putting it is not precisely accurate. It isn’t that public schools have no god; in fact they place many gods before God. Superficial thinkers suppose that unconditional loyalties – whether of the “woke” or another variety -- don’t count as religion just because they don’t use the word “god” for their gods. But the crux of the matter does not lie in the words they use.

|

Read the Fine PrintMonday, 08-11-2025

Most people know the importance of carefully reading contracts before signing them and labels before using the product. All sorts of poisons can be hidden in the fine print. What most people don’t know is that fine print is also a means of advancing the international culture war. (And yes, it is international. Did you think globalization was only about markets?) If you read the UNESCO documents on childhood sexuality education, for example, you will find pages and pages about protecting children from sexual abuse. Sprinkled through them are much briefer passages which let the cat out of the bag -- but you have to look for them. It’s true that the activists who run these agencies don’t want children to be raped. But they do want to sexualize them, and they want it very much. They explain that “comprehensive sexuality education” “equips” young people including children to develop sexual relationships. Among its many goals are that five-to-eight year olds are to be taught that they can masturbate and it will give them pleasure; nine-to-twelve year olds, that abortion is safe; and twelve-to-fifteen year olds, that there are various and sundry “gender identities” which deserve equal respect. Speaking of so called gender identities: The UNESCO documents don’t list them, but did you know that activists now claim that some people are “xenogender”? That’s a gender “that cannot be contained by human understandings of gender.” I wonder: If it can’t be contained by human understandings of gender, then how do the activists know that it is one?

|