The Underground Thomist

Blog

ContentmentMonday, 08-10-2015

I am going to have to stop calling Mondays student letter days, because I make so many exceptions. But the Canadian author of this letter was a student not too long ago. Question:Can you please define "contentment"? What does being content look like in our daily lives? Does striving for increase (career advancement, higher education, a better car, a bigger house, etc) narrow contentment? Is there something as spiritual contentment? Would contentment be a good thing or bad for our spiritual lives? Reply:Most people take for granted that a good life is a life that contains good things. Whether this is true depends on which kinds of good things we are talking about. Have you noticed that each of the kinds of good you mention is at best a conditional good? Having a bigger car, for example, would be helpful if you needed the extra room to pack in all your children, but it would be bad for you if you were going to use it to flee from the police in a life of robbing banks. To put it another way, the conditional goods can’t make your life a good life – but if you are living a good life, some of the conditional goods might become good things for you. The goods that do make life good are called intrinsic goods – these are the goods that are good in themselves, the goods that are unconditionally good. One example of an intrinsic good is virtue, epitomized by wisdom, courage, justice, temperance, faith, hope, and love. Another example is friendship – not just any kind of friendship, but partnership in a good life, because good is diminished if it can’t be shared. Such things literally can’t be bad for you. I am sure you can add to the list of intrinsic goods. Be careful, though, because we often mistake conditional goods for intrinsic goods. Consider career advancement. If I had a calling for administration, then to accept a so-called promotion to an administrative position might be a very good thing. For me personally, though, accepting an administrative position would be a betrayal, because my calling is teaching and scholarship. So career advancement, as conventionally understood, is a conditional good, not an intrinsic one. You might now be expecting me to say that contentment is simply having the intrinsic goods. Not exactly. One can have friends, family, and meaningful work in a life of virtue, and still ask “Is this all there is?” There is only one good so complete and perfect that it leaves nothing further to be desired. This good is the vision of God, which nobody experiences fully in this life, but which the blessed experience in heaven. All of the other goods finally come into their own in this beatific vision. For example, just because it is the perfection of friendship with God, it carries with it perfect friendship with all of His friends. You close with the question, “Would contentment be a good thing or bad for our spiritual lives?” Let me put it this way: To be on the path toward the vision of God is the whole point of our spiritual lives. But to settle for anything less – to imagine that we can be ultimately contented by anything in this life -- would be the greatest possible calamity; it would be to trade our ultimate good for eternal unfulfilled desire and unrest. I might add that the very fact that nothing in this life fully contents us forms one of the arguments for the existence of God. The argument goes like this: There is exactly one longing that nothing in the created order that can satisfy; anyone who does not recognize it in himself does not know himself. Assuming that each of our longings is for something -– what would be a point of a longing that nothing could fulfill? -– it follows that the object of this one longing must lie beyond the created order. This is what we call God.

|

Hate CrimesSaturday, 08-08-2015

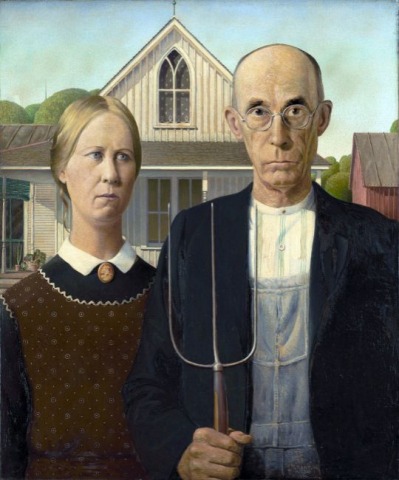

Hate crimes are crimes committed because of hatred for members of certain social groups. The premise of hate crimes legislation is that crimes committed from such motives are worse than other crimes. Consider. A man beats up a woman because he hates women. Hate crime. A man beats up a woman because she was promoted and he wasn’t; because he tried to steal her purse and she resisted; because he derives pleasure from inflicting pain on others; because she was seen in public without a head scarf; because the wife of another man paid him to do it; because he was ordered to do it by the leader of his gang; or because he was rioting and got caught up in the moment. Not hate crimes. Each of these acts is despicable. But how is the first one worse than the other seven? Answer: It isn’t.

|

“The Same as to Knowledge,” Part 9 of 14Thursday, 08-06-2015

Why Guilty Knowledge Leaves TelltalesI believe that the reason guilty knowledge leaves telltales is that the violation of the conscience of a moral being generates certain objective needs, including confession, reconciliation, atonement, and justification. These are the greater sisters of remorse; elsewhere, borrowing from Greek mythology, I have called them the Furies. Now if I straightforwardly repent of my deed, then I make an honest effort to satisfy these avengers of guilt. I respond to the need for confession by admitting that I have done wrong; I respond to the need for reconciliation by repairing broken bonds with those whom I have hurt or betrayed; I respond to the need for atonement by paying the price of a contrite and broken heart; and I respond to the need for justification by getting back into justice. But what happens if I am in denial? The Furies do not go away just because I want them to. What happens is that I try to pay them off in counterfeit coin. I try to pay off the need for confession by compulsively admitting every sordid detail of my disreputable deed except that it was wrong; I try to pay off the need for reconciliation by seeking substitute companions who are as guilty as I am; I try to pay off the need for atonement by paying pain after pain, price after price, all except the one price demanded; and I try to pay off the need for justification by diverting enormous energy into rationalizing my unjust deeds as just. Such behaviors are matters of everyday observation. To be sure, they are difficult to study systematically. Even so, much of the data about the psychological effects of abortion, from both law and the social sciences, are strongly suggestive, though of course, as one would expect in such a case, they are disputed.[11] Someone might suggest that all these supposed telltales are imaginary, that the behavior I call “acting guilty” is more naturally explained in other ways. If I think my behavior has been blameless, why not talk about it? There is no need to think that I am engaging in some sort of displaced confessional urge. If my friends unreasonably subject me to moral criticism, why shouldn’t I drop them and make new ones? There is no need to think that I am trying to find a substitute for supposedly having hurt them. If I am doing things that aren’t good for me, why shouldn’t we write my behavior to bad judgment? There is no need to think that I am punishing myself. If some people view my behavior as wrong, but I disagree with them, why shouldn’t I defend myself? The argument that I am making excuses is circular; it assumes what it sets out to prove. But when I speak of displaced confession, reconciliation, atonement, and justification, I have in mind cases in which these other explanations seem to fall short. We turn to these in the next post. Notes11. As to the law, see for example Sandra Cano v. Thurbert E. Baker, Attorney General of Georgia, et al., on Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, Brief of Amicus Curiae J. Budziszewski in Support of Petitioner, Section VI, “The Affidavits of Post-Abortive Woman Submitted to the District Court in This Case Confirm that the Violation of Conscience Has Destructive Consequences.” (This was in support of a petition for reconsideration of Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton.) As to the social sciences, see for example David M. Fergusson, L. John Horwood, and Joseph M. Boden, “Abortion and Mental Health Disorders: Evidence from a 30-year Longitudinal Study,” British Journal of Psychiatry 193 (2008), pp. 444-451.Link to Part 10 of 14 |

Heavenly Father, Please Disregard the Previous PetitionWednesday, 08-05-2015

A prayer frequently offered during worship: “May our country’s leaders end their bickering and work to solve the country’s problems.” No doubt this petition is innocently intended. However, its premises seem to be as follows. 1. Politicians quarrel not because they have fundamentally opposed views of what their job is and how to do it, but because they don’t want to do their job. 2. Their job is not to govern – that is, to preserve a just order -- but to “lead” – that is, to solve all the country’s problems. One might as well pray, “May the constitutional system of checks and balances continue to fail. May the principle of subsidiarity continue to be violated. May everything that needs to be done in our country be done by an omnicompetent government. May fundamental disagreements be ignored. May one faction crush all others so that only one view remains.” Thy will be done, O Lord. Please, please, not ours.

|

Should I Pretend to Be Grateful?Monday, 08-03-2015

Monday – student letter day! Question: I am an incoming college freshman who has a philosophical disagreement with my dad (whom I respect dearly). After receiving a large graduation donation from my southern grandparents, we discovered that I differed from his approach to integrity in reactions to gifts. As someone who we both respect, I'm asking if you can answer this: Should we show fake or overreacted gratitude in order to fulfill the desires for validation of the giver? My thought is that not only is showing your honest gratitude more valuable, but also deceiving others is clearly wrong. He says that you should over-act to show value to the recipients if their culture values overreaction. Reply: Well, I don’t know what you mean by excessive gratitude, but I think you are asking the wrong question. Instead of asking whether you ought to act more grateful than you feel, you should be asking how grateful you ought to feel -- and then acting that way! The answer to the question “How grateful should I feel for a generous gift?” – by the way, it is a gift, not an obligatory “donation” -- is “very grateful indeed.” So act very grateful indeed! For starters, you might write your grandparents a letter thanking them warmly for their gift and telling them all about your college plans. If they live nearby, you could take them out to lunch at your own expense and tell them over the meal instead. A letter now and then while you’re at school, telling them how things are going, would be a good idea too. Your objection is that you ought to act how you feel. You’re wrong -- there is no such moral law as “Always act how you feel.” Sometimes the moral law requires us to act differently than we feel; in fact, sometimes it even requires us to try to change our feelings. Gratitude is something you owe your grandparents, and you should give to each person what you owe. So you should act with gratitude, and also try to feel grateful. If you don’t yet feel grateful, you should at least act as though you do. You should be concerned enough about the fact that you don’t feel that way yet to want to become a different person. Before I end this letter, let me clear up two other confusions in yours. One of them concerns the meaning of sincerity. Of course we shouldn’t tell lies. Sinful creatures that we are, however, our feelings are often at war with the persons we ought to be. One of the things that we can do about this is wear a mask, just as beautiful as we can make it. This is called courtesy. Masks, of course, can be used to deceive, but in courtesy, our motive is different. As C.S. Lewis pointed out, I wear a courteous mask partly in the hope that my true face will gradually grow to fit it, and partly in the hope of not setting a bad example in the meantime. The words of courtesy, such as "If you please," "thank you," and "the pleasure is mine," may be mere formulae, but they rehearse the humility, gratitude, and charity that I know I ought to feel, do not feel yet, and hope to feel in the future. The other confusion concerns the meaning of selfishness. You suggest that your grandparents’ expectation of gratitude is merely a selfish desire for validation. That’s a little bit like a husband viewing his wife’s expectation of faithfulness as a selfish desire for security, a customer viewing the shopkeeper’s expectation of being paid as a selfish desire for income, or a big fellow viewing a little fellow’s expectation of not being hit in the nose as a selfish desire for physical comfort. On the contrary, gratitude is a moral law, just like faithfulness, justice, and consideration are moral laws. It isn’t selfish for your grandparents to hope that you will be a virtuous grandson who appreciates their gift. There would be something wrong with them if they didn’t want that. The real selfishness lies in thinking their hope selfish. I’m glad you have respect for your dad. Try to have a little more for your grandparents. I hope this is helpful.

|

… and Lying for DeathFriday, 07-31-2015

On Tuesday and Wednesday I criticized the use of evil means to combat the evil of abortion. Let’s return to the evil of abortion itself. Even a few abortion supporters are stunned by the complacency of the Planned Parenthood officials caught on video negotiating the sale of aborted baby body parts. A talking head on one of the interview programs declared that although she was “staunchly pro-choice,” she was horrified by the desecration of human tissue which these sales involve. We should welcome the opportunity such shock presents to achieve a short-term tactical alliance to press for the enforcement of existing laws which prohibit such sales. But the strategic purpose is to change minds about abortion. And that can be done. After all, it’s not easy to believe that it “desecrates human tissue” to market it after it is dead, but doesn’t desecrate it to slice it into quivering pieces while it is still alive. Logically, if one is desecration, then both are. Even so, as progress must be measured in times like ours, this is progress. Something of the truth must still be glinting through the cracks and crevices of conscience, or else not even the lesser desecration could be seen for what it is. The task is to pry open those cracks and let out the rest of the light.

|

“The Same as to Knowledge,” Part 8 of 14Thursday, 07-30-2015

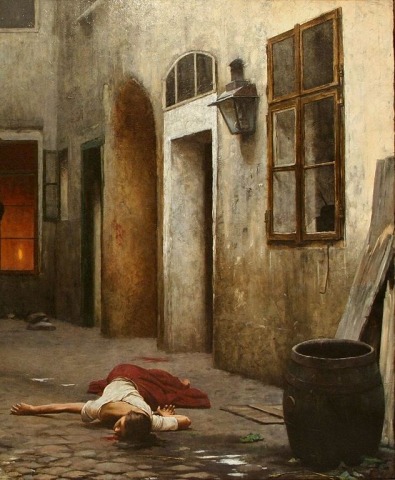

So What Does This Explain?But why, in the end, should we believe that everyone really knows the general moral principles? I suggest an argument to the best explanation. If the hypothesis of moral denial provides a better explanation of how people at odds with moral basics act than the alternative hypothesis of moral ignorance provides, then the hypothesis of moral denial is probably true, and we are justified in accepting it. I think denial does provide a better explanation than moral ignorance. I rest this judgment on the observation that people who are at odds with the moral basics tend to “act guilty.” So strong is this tendency that many guilty people expend enormous energy in the effort not to act guilty. Although some guilty people are better at this than others are, the strain shows. Please notice what I am not suggesting. I am not suggesting that the guilty person is necessarily thinking to himself “I am guilty.” But according to St. Thomas he does have a natural dispositional tendency to be aware of the first principles of natural law and their proximate, general corollaries, and I am suggesting that he also has a natural dispositional tendency to judge his behavior as wrong when it obviously violates these principles. He can resist these dispositional tendencies –- for example, he can try not to think of certain subjects, or try to find ways of viewing the obvious as not obvious -- but if he does, then he is also going to have to fight the dispositional tendency to be aware that he is resisting. Three sets of intellectual “habits” are therefore in conflict: First, all those associated with the natural habitus of the knowledge of the general principles of the natural law; second, all those associated with what I consider a natural habitus of knowing when I have violated them; and third, all those associated with the acquired habitus to resist the actualization of this knowledge. Second, I am not suggesting that a dispositional tendency to act guilty proves that the person manifesting it must really be guilty of something; it only proves that he has a dispositional tendency to believe that he is guilty. Such belief may be unwarranted and false. For example, I may blame myself because I survived an automobile crash that killed everyone else, even though I was not driving and was not at fault. However, when my belief in my guilt is warranted and true, it is knowledge. So consider a person who has murdered, who claims to believe that murder is no big deal, and yet who acts guilty. I say that although he claims not to view murder as wrong, he knows better. Third, when I speak of acting guilty I am not suggesting that it is always easy to tell precisely what guilty knowledge is being betrayed. To be sure, sometimes it is easy to tell, for example, when a person displays a compulsion to tell everyone about what he did even though he insists that his behavior was innocent. But sometimes it isn’t at all easy to tell; a person may engage in behavior strongly which is suggestive of self-punishment, but which does not advertise what he is punishing himself for. Fourth, I am not suggesting that people who are at odds with the general principles of natural law always feel guilty. Guilty feelings – sorrowful pangs of remorse -- are probably the least reliable sign of guilty knowledge. No one always feels remorse for doing wrong; some people never do. Yet even when remorse is absent, guilty knowledge generates other telltales – to which we turn next. Link to Part 9 of 14 |