The Underground Thomist

Blog

Do Most People Want the Same Things?Wednesday, 11-24-2021

Recently I spoke with a highly intelligent lady who was puzzled by the divisions of our times. “I can’t understand them,” she said, “because I think most people want the same thing.” She reasoned that something must be muddying the picture, giving the impression that people disagree more than they do. She and other participants in the conversation suggested several possible muddiers. Biased news reporting. Twitter, and other social media. The power of money in politics. There was a good deal to these suggestions, but even so I was a bit skeptical about the premise that most people want the same thing. Having been less than successful in explaining why, I probably left an impression of cynicism. Well, that’s the nice thing about having a blog. You can have another go. Do most people want the same thing? When we discuss this question, we usually talk past each other, because the answer depends on what we mean. In one sense, all people do want the same thing. Everyone wants to be happy, and it isn’t even possible to will some course of action except “under the aspect of good.” Nobody pursues unhappiness, nor anyone evil, for its own sake. But people may entertain radically different conceptions of what happiness is and how it is to be attained, and they are capable of justifying great wickedness “under the aspect of good.” Anyone who gives thought to the matter will realize that in fact, there is no other way in which wickedness can be justified. Evil trades on good; that’s how it works. Burn down stores in the name of justice. Mock and oppress those who disagree with you for the sake of toleration. Pervert the administration of justice so that bad people won’t have their way. Falsify and suppress history to bring a better tomorrow. Drag filth into public schools so that children will cherish diversity. Twitter and all those other things can exacerbate such perversions of the good, and that is important. But they don’t generate them. Agreement at one level, with conflict at another, is an inevitable condition of life under the conditions of the Fall. There really is a law written on the heart, and this is a permanent advantage of good. But moral laws can be made engines of their own violation, and this is a permanent advantage of evil. To forget the former advantage is to risk losing heart. To forget the latter one is to risk becoming naïve.

|

Can We Believe and Feel Things at Will?Monday, 11-22-2021

Persecutors think we can believe things at will. That’s why they think that if only they break enough of our knuckles, or yank out enough of our teeth, we may start accepting the teachings of the Party. However, hardly anyone else thinks we can believe things at will. “I can’t believe something just because I want to.” The situation is actually more complicated. A student told me once that she believed in God but was in terror of losing her faith. In the course of conversion it became pretty clear that for some time she had been looking very earnestly for reasons not to believe in God, for example by seeking out courses from all of the professors who were most hostile to faith. She visited me, I think, because success in her enterprise was coming a little more quickly than she was prepared for, and she panicked. So no, we cannot literally believe or disbelieve things at will, but for better or for worse, we can willfully place ourselves in situations or courses of action that may produce change in our beliefs. Concerning whether we can feel or not feel things at will, the situation is much the same. We’ve all heard the mantras -- Feelings are neither right nor wrong. They just are. I can’t help how I feel; I just do. How I feel is who I am. And it’s true that we can’t shut off unwanted feelings like a switch. It’s also true that the very effort of trying to suppress them can stir them up. Even so, our control over our inward life is much greater than we like to admit, just like our control over our beliefs. Although I may not be able to keep an unwanted guest from entering the house of my feelings, or to force her outside after she has entered it, yet nothing compels me to ask her in. Nor am I compelled to sit down and admire her, to enjoy her attentions, or to invite her to play with my imagination. If I ignore her and go about my business, she will eventually leave my mind on her own; but if I pet her, say, “Don’t go yet”, and tell her what a lovely feeling she is, she will return another day in power, and that day she will burn down the house. The false notion that we are helpless in the face of our feelings is deeply ensconced in popular music, usually in connection with the pleasures and pains of love. The singer is said to be chained or enslaved to love. He begs to be set free. He loves someone inappropriate, but asks “What else can I do?” Well, by that time the horse has escaped from the barn -- but had he acted earlier, he could have done quite a bit. The more time I spend with a person, the more likely I am to fall in love with her. The best way to avoid falling in love with an inappropriate person is to decide ahead of time which sorts of persons are appropriate, and spend time only with them.

Postscript and ClarificationFrom a gracious reader of this blog: But isn’t faith an act of the will? Yes, but the virtue of faith is a “infused” virtue, and the act of faith is not an act of the unassisted will, but of the will assisted by grace. We can cooperate with grace – as we can refuse it -- but we can’t work it up in ourselves by dint of moral effort.

|

LoiteringMonday, 11-15-2021

In 1892, the U.S. Supreme Court, acting as censor morum, declared that America is a Christian people. Sixty years later it modified the claim, calling us a religious people, whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being. The difference between the two statements is profound, for almost anything can count as religious. Proof, were it needed, came in 1968, when Justice Douglas, speaking for the Court, asserted a right to use pornography because of the importance of “man’s spiritual nature.” Where are we now? Some have gone so far as to characterize contemporary American pop spirituality by the motto ABC: “Anything But Christianity.” There is some truth to the portrayal. Large numbers of us are willing to try Zen, yoga, channeling, séances, astrology, past-life regressions, transcendental meditation, the reading of omens, the chanting of mantras, the casting of spells, the use of charms, the induction of abnormal mental states by drugs, the cultivation of out-of-body experiences, the ritual offering of milk and honey to Sophia or of aborted babies to Artemis -- anything but faith in the one whom Christians call the resurrected Lord. Because of the strangeness of these practices and associated beliefs, the ABC segment of our folk religion receives a great deal of attention. I suggest, however, that the attention given this segment is far out of proportion to its numbers. For the greatest part of American pop spirituality seems to be formed by the confluence of two streams, neither of which can be characterized as simply ABC: A stream of people fleeing Christian orthodoxy, who have paused, for some reason, on the way out, and a stream of people attracted to Christian orthodoxy, who have paused, for some reason, on the way in. If these two groups have much in common and are attracted to many of the same authors, it is because they are loitering at the same gate, comparing and exchanging their articles of luggage. They dabble with the beliefs and practices listed above, but they dabble with orthodox beliefs and practices as well. Because the representatives of these two streams never offer theological reasons for lingering, one cannot help but wonder just what arrests their respective movements. One writer I encountered, a best-selling minister who loitered on the way out the exit, seemed to have a sheer sentimental attachment to congregational fellowship. Another, a best-selling psychologist who loitered on the way in, seemed burdened by the awful weight of sudden and unexpected guruhood. Having passed in both directions through the portal myself, I am interested by such things. But because they are not such things as can be learned from books, let us consider the things that can. Particularly interesting is the selectivity of such writers' borrowings from orthodoxy. The second of the two fellows I mentioned borrowed a belief in the existence of various created spirits -- some of them angels, others deceivers. But he had no use for scriptural guidelines for telling them apart, much less for the scriptural prohibition of sorcery; thus he practiced unsupervised exorcisms of the ones he considered bad and “channeled” the ones he considers good. This is a good deal more than chilling. The other was also selective, though in a sillier way. For instance the idea of Holy Communion attracted him, but heaven forbid that it should be undertaken with bread and wine, for the elements Jesus instructed his followers to use might suggest, he said, a “theological interpretation.” One fine Sunday, therefore, the good reverend sprang tangerines on his congregation, reasoning that the problem of dealing with pits and peels and so forth would encourage cooperation. Another week he tried animal crackers. Over time he also experimented with Gummi Bears, jelly beans, M&Ms, and Pop Rocks. Unfortunately the animal crackers provoked a free-for-all among the children, the M&Ms melted in the hands, and the Pop Rocks produced a lavender froth around the lips. His conclusion? “Reformation is never simple, never easy, never quick.” So it is that people of two such different streams, some of them refugees from something like orthodoxy, the others just arrived from regions adjacent to Zen, converge at the gate and pause. Contemporary American pop spirituality is a theology of lingering, of loitering, of hesitation, a religion of the vestibule. It wants connectedness without commitment, reconciliation without repentance, and sacredness without sanctity. It wants to sing the songs of Zion in the temples of Ishtar and Brahman – or vice versa. God help us to know what we want and to want what we ought. God make haste to help us; God make speed to save us.

|

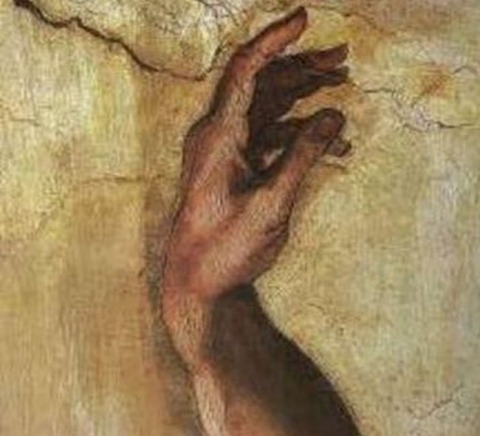

If Man Is the Image of GodWednesday, 11-10-2021

The logic of the matter is that since contingent effects require causes, and contingent causes require causes, there must be a first cause that is not contingent but rather has to exist. This being the case, if we ask “What if there were no God?” we are trying to draw conclusions from an impossible premise, which is a recipe for nonsensical conclusions. But of course people do ask the question. It is not a logical but a psychological enterprise. Very well, let us consider the psychology. The sequence of ideas tends to work out something like this. If God is dead, everything is permitted. We’re heard that one. But if Man is the image of God, Man is dead too. And then everything is even more permitted.

|

It’s MY Purpose. Hands off.Monday, 11-08-2021

Query:In an explanation of St. Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on Law, you say that the purpose of the common good “belongs” to the whole people. Could you tell me how a purpose "belongs" to someone? Any light you can shed on this would be very much appreciated.

Reply:I don’t mean anything terribly abstruse. A purpose belongs to me if it’s my purpose, belongs to you if it’s your purpose, and belongs to the community if it’s the community’s purpose. Terms like “my” can be puzzling because they are used in different senses. For example, if I speak of “my” car, I mean that I own it, but if I speak of “my” wife, I mean that I am the person who is related to her as husband to wife. How then is a purpose mine? It’s mine when I am interiorly ordered or directed to it. Ordered or directed to it how? Well, it may be my subjective intention (for example, I may want to get some ice cream), it may be my inbuilt or natural purpose (for example, even if I want to die, I am naturally directed to life and flourishing), or it may be both (I am naturally directed to life and flourishing, but I subjectively aim at a flourishing life too). We’re also speaking in both senses when we say that the purpose of the common good “belongs” to the political community. Certainly the community cannot be said to flourish unless it really is enjoying the common good; as Aristotle says in Politics, Book 1, the city “comes into existence for mere life -- but exists for the sake of living well.” So the purpose of the common good is natural to it. But unless the common good is the city’s subjective intention too, it is hardly proper to call the city a “community.” The very phrase calls attention to what it cherishes and pursues in common. I hope I’ve cleared up the puzzle!

|

Universal Higher Education -- Just a ThoughtThursday, 11-04-2021

Sending everyone to college hasn't given everyone a college education. That can't be done. It's given everyone what used to be a high school education. A very, very expensive high school education.

|

The Genetic Basis for SacrificeMonday, 11-01-2021

If evolution is driven by the survival of the individual, then it’s pretty hard to explain why anyone would sacrifice for anyone else, since any impulse to do so should have been bred out of us long ago. Theorists of “kin selection” propose a solution to the puzzle. Does it work? According to this theory, the unit of natural selection isn’t the individual, but the gene. My close relatives share a lot of my genes, so in some cases the survival of the genes we share – in this case, the very genes for sacrificing for relatives -- is better promoted by my sacrificing for them than by my clinging to life at their expense. Such explanations do have value. Kin selection explains some animal behaviors quite well. In the case of the social insects, it has been a spectacular success. But if kin selection is all there is to it, then why would I ever sacrifice for neighbors who aren’t close relatives, persons with whom the value of my coefficient of genetic relatedness is very small? Evolutionary psychologists have an answer to this one too. I am able to sacrifice for non-relatives by viewing them as though they were my relatives. After all, don’t we say that all men are brothers? And don’t we call that saintly woman Mother Teresa? Hold on a moment: The explanation doesn’t work. If the kin selection hypothesis is true, then although sacrifice for close kin is adaptive, sacrifice for unrelated people whom we merely think of as though they were close kin is maladaptive. On balance, it makes the survival of my genes less likely, not more. So by this hypothesis, even though we should be strongly motivated to sacrifice for real kin, we should be strongly averse to sacrificing for merely figurative ones. We may concede that the impulse to sacrifice for non-kin is rather weak and unreliable. But it exists. Moreover, we applaud it and believe that we ought to cultivate it. On the kin selection hypothesis, not only should the impulse to sacrifice for non-kin not exist – not only should we have the opposite impulse – but we shouldn’t even think we ought to cultivate such a motive, for the inclination to think so would be maladaptive too. We should have evolved to think that we shouldn’t view all men as brothers. So there are two possibilities. 1. Natural selection is the whole story, but we don’t yet have all of the pieces. 2. Natural selection isn’t the whole story. The materialist will back hypothesis 1. He will do so on grounds of faith – and yes, it is a faith – that material nature is all there is, so that even if we don’t see how it could be, one day we will. I find a faith that is open to the possibility of additional, non-materialistic explanations much more persuasive and interesting. Follow the evidence where it leads. Related:What Conscience Isn’tSo-Called Evolutionary Ethics

|