The Underground Thomist

Blog

Trusting in PrincesMonday, 01-02-2017

Commenting on CBS This Morning on the end of her husband’s term of office and the election of a rival, the outgoing First Lady said “We feel the difference now. See, now, we’re feeling what not having hope feels like.” It is said that in Washington, she and her husband attend an Episcopalian church. I guess the following passage has never been discussed during worship. Put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no help. When his breath departs he returns to his earth; on that very day his plans perish. Happy is he whose help is the God of Jacob, whose hope is in the Lord his God, who made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them; who keeps faith forever; who executes justice for the oppressed; who gives food to the hungry. -- Psalm 146:3-7 (RSV-CE) |

The Infant’s VoiceSunday, 12-25-2016

Yesterday I displayed a few gems from a Christmas Vigil sermon by Bernard of Clairvaux. These are from a pair of his sermons for Christmas Day. I have taken a few liberties with the translation, which is a bit dated.+++ + +++ Christ is born in a stable, and lies in a manger. Yet is He not the same that said, The earth is mine, and the fullness thereof? Why, then, need He choose a stable? Plainly that He might repove the glory of the world, that He might condemn its empty pride. +++ + +++ I have already said that He preaches to you even in His infancy: “Do penance, for the kingdom of God is at hand.” The Stable preaches this penance to us; the Manger proclaims it to us. This is the language which His infant members speak; this is the Gospel He announces by His cries and tears. +++ + +++ And lest thou should say even now, I heard thy voice, and I hid myself, behold, He comes as an Infant, and without speech, for the voice of the wailing infant arouses compassion, not terror. If He is terrible to any, yet not to thee. |

More Than Long AgoSaturday, 12-24-2016

These rubies are from a Christmas Vigil sermon by Bernard of Clairvaux.+++ + +++ Let no one be so indevout, so ungrateful, so irreligious, as to say: This is nothing new; it was heard long ago; Christ was born long ago. I answer: Yes, long ago and before long ago. No one will be surprised at my words if he remembers that expression of the Prophet, in aeternum et ultra, “for ever and ever,” or “for ever and beyond it.” Christ, then, is born not only before our times, but before all time. ... That this mysterious Nativity might to some extent be made known, Jesus Christ was born in time, born of flesh, born in flesh, the Word was made flesh. +++ + +++ Tomorrow, therefore, we shall see the majesty of God, but with us, amongst us, not in Himself. We shall see Majesty in humility, Power in weakness, the God-man. ... He chose a stable and a manger – yes, a despicable hut, a shed fit only for beasts – that we may know that He it is “Who raises up the poor one from the dunghill” [and] Who said, “Unless you be converted and become as this little child, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.” |

Off With Their Heads!Tuesday, 12-20-2016

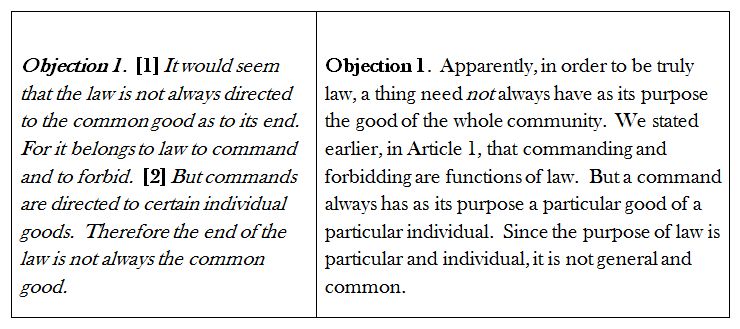

Two small errors turned up in the hardcover edition of my Commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on Law. Although they were corrected in the paperback, a reader suggests that I post the corrections here too. Good idea. The first error is rather funny: On the cover, the word Commentary was spelled with three M’s. If you have one of those copies, better hold onto it: Odder things have become collectors’ items. The second error was on page 28, in the discussion of Question 90, Article 2, “Whether the Law is Always Something Directed to the Common Good?” St. Thomas’s answer is “Yes,” but the Article begins with three Objections – reasons why someone might think the answer “No.” Right after the paragraph beginning with the words “More broadly,” the text and paraphrase of Objection 1 were omitted. Here is what the Objector says:

The omission is now fixed, and everything else was where it should have been. To show how it all goes, here is my line-by-line commentary on Objection 1 (which of course is only a small part of the Article): “The Latin expression [the Objector] uses here for the shared or common good is bonum commune, which can equally be translated ‘the good of the community.’ He is thinking of the community not merely as an aggregation of individuals who may be at odds with each other, but as a true partnership in a truly good life. To further develop the idea, however, we need to distinguish between two senses in which a good can be common. “In the weak sense of the term, a good is common merely when it is good for everyone, like pure water. Different people in the community may enjoy different amounts of goods that are common in this weak sense. In fact, if one person grabs more of a weakly common good, then other people have less. For example, I might divert part of the river away from your property and onto mine. “In the strong sense of the term, though, a good is common when one person’s gain is not another’s loss, so that our interests literally cannot diverge. For example, the goods of character are strongly common -- I do not become less wise, or less just, or less courageous, just because my neighbor becomes more so. Another example of a strongly common good is the security of the community -- if you and I are fellow citizens, and our country is invaded by a hostile power, then it is invaded for both of us. It is impossible for our country to be invaded for you but not for me. “Sometimes [St. Thomas and the Objector] use the expression ‘common good’ in the strong sense, but sometimes only in the weak. One must pay close attention to keep from getting mixed up. Consider his discussion of distributive justice in II-II, Q. 61, Arts. 1-2. Distributive justice is the allocation of certain things to members of the community according to what is due to them. Now it is good for the community as a whole that its greatest benefactors attain the highest honors and offices; everyone is better off as a result. This shows us that distributive justice is a strongly common good. But St. Thomas also calls the honors and offices themselves ‘common goods.’ What kind then are they? Since some citizens receive a greater share of them than others, obviously they are not common in the strong sense; they are merely things that anyone may see as good. We see then that although distributive justice is a strongly common good, the things that it distributes are only weakly common goods. “More broadly, the aspect of justice that concerns the common good is called ‘general’ justice. Special justice is doing good and avoiding evil in relation to my neighbor, with a view to what I owe him. But general justice is doing good and avoiding the opposite evils in relation to the community, or to God. [II-II, Q. 79, Art. 1; compare II-II, Q. 58, Art. 6.] “[1] [The Objector] does not mean that the law only commands and forbids; as he explains later, in Q. 92, Art. 2, its acts also include permitting and punishing. Commanding, forbidding, permitting, and punishing are direct acts of law. Doesn’t it accomplish other purposes as well, such as directing, rewarding, and encouraging? Yes, but these purposes are achieved indirectly, mainly through commands and prohibitions, backed up by punishments for failure to comply. For example, the law directs traffic through forbidding excessive speed, and it rewards acts of valor through commanding that soldiers who have performed them be awarded medals. “It might seem that permitting is not so much an act of law as the omission of an act, because we take anything not explicitly forbidden to be permitted. However, certain kinds of permissions must be made explicit, because they provide individuals with ways to modify the legal obligations they would otherwise have. For example, the law encourages home ownership and construction through explicitly permitting homeowners to deduct mortgage interest from personal income taxes. By taking advantage of this permission, homeowners alter the amount of taxes they would otherwise be commanded to pay. “[2] Individual goods are goods of particular individuals. Sometimes the law issues commands like ‘No one may steal the property of any other person.’ This is quite different from a command like ‘No one may pollute the community water supply,’ because the other person is not the community as a whole, and his property, unlike the water supply, is an individual good, not a common good. From this, the Objector concludes that law does not always aim at the common good.”

|

The Object of Uttermost LongingMonday, 12-12-2016

Query:What would you say is the single most compelling, prima facie argument for God? Reply:The argument I find most compelling is sometimes called the Argument from Desire. At the very beginning of the Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas says that “To know that God exists in a general and confused way is implanted in us by nature, inasmuch as God is man’s beatitude.” What does this mean? We naturally long for beatitude, for that complete and utter happiness which would leave nothing further to be desired. But “nature makes nothing in vain” – thirst is quenched by water, hunger is filled by food, and in general, for every basic desire there is something that can satisfy it. So there must be Something that could satisfy the longing for beatitude. That Something, that supremely loveable object of the longing for beatitude, is God. Ah, but how far short of knowing what God is such knowledge falls! If we know God only as the mysterious object of the longing for beatitude, and if we mistakenly suppose beatitude to lie in some merely natural good – say, pleasure, beauty, or erotic love – then we will mistakenly take that good as our “god.” So can we go further? Fortunately, we can, because experience shows that every natural good leaves something further to be desired. In fact, the totality of all natural goods leaves something further to be desired. The world is so achingly beautiful, and yet it keeps breaking our hearts. We keep asking, “Is this all there is?” It follows that if the longing for beatitude really does have an object, it must lie not within nature, but beyond it. Taken together, the various arguments for the existence of God tell us quite a bit about Him: For example, that He is the First Cause of all things and the Source of all Good, and that there is only one of Him. That isn’t enough, is it? Not even all the philosophical arguments together can tell us that He has come among us, shared our burdens, and atoned for us. For that, we must consult testimony of witnesses -- which is to say, the Gospels. Even so, the philosophical arguments do faith a great service. They are preambles to faith, because they show it to be reasonable to believe in the sort of God of whose deeds the Gospels teach. The emeritus Pope has remarked that Christians used to say to pagans that the God whom we worship is not some god of myth, like theirs, but the God of whom the philosophers spoke -- but whom they did not worship. They knew Him only as a theorem. We know Him as Immanuel, God with us. You might be interested in this little riff on the Argument from Desire. It was my pre-Christmas post two years ago: |

Full CircleMonday, 12-05-2016

Men think they may do as they please. In order to limit them, among other things the law of Moses prohibits disproportionate revenge: One may take an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, but not a life for an eye or a limb for a tooth. To men who have been successfully shaped by that wise law, Christ explains that in fact, the God Who gave it does not desire men to take revenge at all. Some centuries later, theological revisionists argue that if revenge is really wrong, then the law of Moses is defective. Still later revisionists conclude that if the law of Moses is defective, then Divine Revelation is illegitimate. In that case the revelation of Christ is illegitimate too. Men think they may do as they please. +++ + +++ To subscribe to this blog, just go here. |

Mean MoralistsMonday, 11-28-2016

I am glad to say that after receiving my response, this fellow made a gracious reply. Query: I've begun your guide because even as an atheist I believed in abiding universals and liked Epictetus and Cicero. I have a complaint with you. I've known women who had abortions who were deeply mournful but their situation was desperate. They were abandoned and couldn't care for themselves. Why don't you moralists do something about the dire conditions children could be born into and are why they're aborted? Another culture issue is same sex marriage. There has always been a small minority of homosexuals and to finally let them love without being thrown off a roof is only decent. Law should not be some imaginary ideal. If people can't do it it isn't moral. Reply: Cicero is one of my favorites too, and I'm glad you recognize that there are abiding universals, though I suggest that a few are missing from your list. Since there is a certain edge to your tone, I don’t want to correspond back and forth. However, you do ask several serious questions, so I will take a chance and respond just this once. “I have a complaint with you. I've known women who had abortions who were deeply mournful but their situation was desperate.” Would you have written that you’ve known women who have killed their toddlers and were deeply mournful, but their situation was desperate? Of course you wouldn’t have, because there are no situations that can justify the deliberate killing of weak and innocent human beings. But unborn infants are also weak and innocent human beings. You don’t suppose those are dogs or porpoises in there, do you? Nor are you doing distressed mothers any favors by encouraging them to kill their own children. Of course they mourn, for the trauma of having been responsible for the death of one’s son or daughter far exceeds almost any imaginable sorrow. They will always remember that if they were unable to care for their children, even so they might have loved them enough to put them up for adoption, and instead they took their lives away. How greatly they and their children need the mercy of God. Your mercy is cold ashes, because you make no effort to dissuade them. “They were abandoned and couldn't care for themselves. Why don't you moralists do something about the dire conditions children could be born into and are why they're aborted.” Really, you should find out the facts. There are thousands of crisis pregnancy centers across the United States alone, staffed mostly by volunteers. These are but a fraction of the pro-life organizations that help women in trouble. Typically, they offer a wide variety of services. The one closest to me offers baby furniture, diapers, baby clothing, child rearing classes, and help with enrolling for social services, among other things. A pro-life shelter I know took in pregnant women who had no place to live, and afterward helped with all kinds of practical needs so that they could get on their feet. If you think that isn’t enough, you might ask yourself what you do for these poor women. “Another culture issue is same sex marriage. There has always been a small minority of homosexuals and to finally let them love ... is only decent.” Would you have written so approvingly of incest? No? Then you agree that the law must make distinctions. Even so, no one is trying to keep anyone else from having loving affection for anyone. I think perhaps you believe that sex makes every kind of love better. A moment’s thought shows that this is false. There are many kinds of love -- between brothers and sisters, soldiers in trenches, parents and children, teachers and students, husbands and wives, and so on -- and only the last one is consummated by sexual intercourse. The other kinds it harms. “... without being thrown off a roof ...” If you do know of anyone sponsoring a law to throw people off roofs, please let me know. I would be very surprised. The usual question is not whether anyone should be thrown off a roof, but whether the law should classify a sexual relationship between two people of the same sex as a marriage. To answer that question, one must consider why there are marriage laws in the first place. The reason is that the well-being of society depends on the well-being of children, and marriage is the only social institution that gives kids a fighting chance of having a mom and a dad. A relationship between two men or two women isn’t a marriage because it has nothing to do with bringing children into the world. The law doesn’t define my relationship with my fishing buddy as a marriage either, for the same reason. “Law should not be some imaginary ideal. If people can't do it it isn't moral.” Certainly it should be possible to obey the law. However, you write as though the law were trying to force persons who suffer the misfortune of same-sex affections to do something they can’t do, like flapping their wings and flying. I am not aware of any such law. +++ + +++ Do you want to know how to subscribe to this blog? It’s easy. Just go here. |