The Underground Thomist

Blog

What Maketh an Exact Twelve Year OldMonday, 04-25-2016

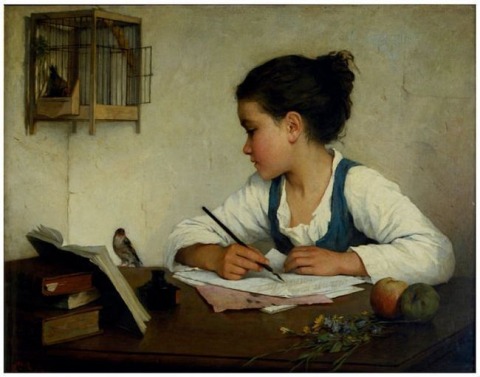

Don't overlook: Book TrailerQuestion:I've been following your blog for a few years now, and I wonder if you could help me. Recently I've recently decided to homeschool my daughter, who will be twelve soon, and was excited at the prospect of having some sort of logic textbook that she and I could delve into together. You wouldn't happen to have a title handy, would you? I am far from being an expert, so she and I will be at almost the same level. Reply:More power to you. We began home-schooling one of our own daughters at the same age. Though I have no logic textbook to suggest for that level, I think twelve may be a little early for a logic textbook anyway. Our approach was to have our daughter keep a logical fallacies notebook. We emphasized the fallacies of distraction, which are challenging enough for an early middle schooler. The formal fallacies can probably wait for a year or two. Each day our daughter had to come up with at least one fallacy. It might come from any written or spoken source, including literature, newspapers, and conversations, but it had to be unintentional – contrived fallacies like the examples in logic textbooks weren’t allowed. Each time she found a fallacy, she had to record it, classify it, explain how it went wrong, and indicate where she had read or heard it. As you might guess, she became quite adept at recognizing some kinds of fallacy. These she would pounce upon with glee. Other kinds were more difficult to spot, but by the end of the year, with just a few hints, she had found at least a few examples of even the hard ones. She took it as a challenge. Since I love to encourage home schoolers, may I throw in another suggestion? As one English author said, “writing maketh an exact man” – so consider giving your daughter a daily brief writing assignment too! Make each writing assignment different. Give each one a twist. Something like this: Tell which you think better, asparagus or broccoli, and justify your answer. Vividly describe what it might be like to be a fish, without using adverbs or adjectives. Rewrite this week’s newspaper weather forecast, in the style of Edgar Allen Poe. Compose directions from our house to the grocery store, making sure they could be followed even by someone who didn’t know the neighborhood. Solve the following simple puzzle, then explain how you worked out the answer. A wicked witch has turned you into a toad. Describe how you could get our attention and explain what has happened, bearing in mind that we don’t know who you are and don’t normally let toads in the house. Just a thought. I hope you both have fun!

|

PretenseSunday, 04-24-2016

Don't overlook: Book Trailer“Every religion is equally valid.” But most religions hold that not every religion is equally valid. So if every religion is equally valid, then it is equally valid to deny that every religion is equally valid. Let us give up the silly pretense of agreeing with everyone; courtesy and reason are enough.

|

Liberty LicenseSaturday, 04-23-2016

Don't overlook: Book TrailerQuestion:You write in your post “How the Meaning of Liberty Did and Didn’t Change” that history presents us with two nearly opposite meanings of freedom. Among the classical thinkers, you say, the term referred not to the absence of governance, but to a certain kind of governance. But among the modern writers, it comes to mean not freedom from the wrong kind of rule, but something more like freedom from rule. How did this shift take place? I suspect that it was messy. Reply:Your suspicion is right. It was messy. In the first place, the ancient meaning of liberty is not entirely unknown to the moderns: When Alexis de Tocqueville writes in Democracy in America about “free” local institutions, he means local institutions of self-government. In the second place, the meaning of liberty which predominates today was not entirely unknown to the ancients: Florentinus is quoted in Justinian’s Digest as defining liberty as “one’s natural power of doing what one pleases, save insofar as it is ruled out either by coercion or by law.” Usually, however, the classical writers called liberty in this sense mere “license,” distinguishing it from liberty in the sense of being able to govern oneself properly. And although the modern writers too distinguish liberty from license, they become less and less able to explain the difference. The new conception of liberty is perhaps most dramatically on display in Thomas Hobbes, who writes in his 1651 work Leviathan that “‘The right of Nature,’ which writers commonly call jus naturale, is the liberty each man hath to use his own power as he will himself for the preservation of his own nature, that is to say, of his own life; and consequently of doing anything which in his own judgment and reason he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto.” He says a few lines later, “it followeth that in such a condition every man has a right to everything, even to one another’s body.” In other words, my “natural” liberty is doing as I please, even if I think I need to kill you. By this way of thinking, the fulfillment of our nature isn’t the cure, it’s the disease. We see in Richard Price, a contemporary of the American Founders, something of how the older language of self-government became blurred so that it actually seemed to mean the mere absence of restrictions. Here is what he says in Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, written in 1776: “By physical liberty I mean that principle of spontaneity, or self-determination, which constitutes us agents, or which gives us a command over our actions, rendering them properly ours, and not effects of the operation of any foreign cause. Moral liberty is the power of following, in all circumstances, our sense of right and wrong, or of acting in conformity to our reflecting and moral principles, without being controlled by any contrary principles. Religious liberty signifies the power of exercising, without molestation, that mode of religion which we think best, or of making the decisions of our own consciences respecting religious truth, the rule of our conduct, and not any of the decisions of our fellow-men. In like manner civil liberty is the power of a civil society or state to govern itself by its own discretion or by laws of its own making, without being subject to the impositions of any power in appointing and directing which the collective body of the people have no concern and over which they have no control.” Price adds, “there is one general idea that runs through them all; I mean the idea of self-direction, or self-government.” Taken at its word, this passage would seem to mean that simply by submitting to a just civil law with which I happen to disagree, I am deprived of my power of self-government. Price doesn’t actually mean this, for in the next section he says liberty is the opposite of licentiousness. So here, when he speaks of conscience, he probably means something like conscience well-formed by the natural law. The difficulty is that he doesn’t say so; he doesn’t specify it in his definition. So conscience comes to seem merely another word for will, which is how many people use the term today. What we see is that more and more of the equipment of the classical natural law tradition was discarded with the aim of clarifying and simplifying matters. Yet rather than being clarified and simplified, they became confused.

|

The Smallest Worm Will TurnFriday, 04-22-2016

Don't overlook: Book TrailerNot so very long ago, many of my students would be angered by the mere suggestion that there might be anything morally problematic about abortion. A decade or two later, the suggestion that abortion might be wrong is much less likely to provoke anger, and a greater proportion of my students concede that the practice is at least morally suspect. So is the pro-life side gaining? In that way, yes. But now the plot thickens. Fewer and fewer of the young people I meet on either side of the abortion controversy consider it a major issue any more. These days, what stirs student emotion is the suggestion that there might be anything morally problematic about extreme sexual promiscuity. That’s especially interesting, because for a while, attitudes toward sexual promiscuity had been going in the other direction. I don’t mean behavior was becoming more chaste; quite the contrary. But students were also becoming much more willing to acknowledge the tawdriness and emptiness of the hookup scene. Sometimes they even expressed relief merely to hear that there might be a rational basis for traditional sexual ethics. These days I hear such comments less often. Mind you, people don’t claim that promiscuity is working for them, but they are angrier and more defensive when someone suggests that it may not be. Not many students on the other side are willing to speak up publically. The result is that I hear one point of view in the classroom, and an entirely different point of view during office hours. Yet an underground movement is growing. In 2005, students at Princeton University founded the Anscombe Society, named after the famous twentieth-century English analytical philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe, for the purpose of affirming “the importance of the family, marriage, and a proper understanding for the role of sex and sexuality.” From this seed sprang the Love and Fidelity Network, a growing alliance of student groups which now has a presence at 39 universities, including Yale, Harvard, Stanford, Brown, Columbia, Duke, UCLA, and the Universities of Wisconsin and Virginia. These students aren’t angry, but they are very tough and smart. Could it be that the little worm is turning?

|

The Treatment of WoundsWednesday, 04-20-2016

A new study from the National Center for Health Statistics, publicized by the Institute for Family Studies, suggests that young American adults may be turning to cohabitation largely because so many of them have painful memories of their parents’ divorce. Who could feel anything but compassion for these young people? Yet to treat the pain of broken commitment by avoiding commitment is like treating a wound by pouring acid into it. Besides, breaking up is painful for cohabiters too. The motives that lead some young people into the hookup culture are not so very different from the motives that lead others to cohabit. They think that by removing sex even further from relationship, they will be spared the sorrow of any sort of breakup whatsoever. Since that is not how we are made, the wheel of loneliness keeps turning.

|

AnonymityMonday, 04-18-2016

Slightly revised: Thank you, readers.Question:I am a regular reader of your blog. Having thought about this question for a while, I thought I would ask for your thoughts. In a recent interview with Benedict XVI, the former pope appears to say that following the Second Vatican Council the church ‘abandoned’ its belief that a person must be baptized, i.e., believe in the Christian faith in order to be saved from “perdition.” As a protestant Christian who admires aspects of the Catholic Church’s doctrine, I found this rather shocking. Is the former pope saying that there is salvation outside the church? I wonder if you might comment on whether I am interpreting his words correctly, whether he is accurately representing the position of the church, and what implications this has for the Catholic faith. The part of the interview I am asking about begins with Benedict’s words “There is no doubt that on this point we are faced with a profound evolution of dogma.”

Reply:There are certainly a number of things in the interview which might not be clear to non-Catholic audiences. For instance, to ask whether a person must be baptized is not the same thing as to ask whether he must believe in the Christian faith. And although Benedict says an “evolution of dogma” is underway, the development of doctrine does not include the possibility of reversal. Actually, in an authentic development doctrine is confirmed through being deepened, clarified, and extended. Let’s get to your question. The Church has always taught that we cannot be saved – “saved” meaning rescued from our alienation from God and reconciled with Him -- except through Christ, who died for us. This doctrine cannot be abandoned. But it does not necessarily follow that we must explicitly place our faith in Christ to be saved through Christ. After all, the holy people of Old Testament times were saved through Christ, but they lived centuries before Christ was born, and did not know of Him. So far we are not saying anything new. The Church has always believed that these holy people were saved not apart from Christ and His Church, but because, in some sense, they placed their faith implicitly in the Christ whom they were expecting but did not know, and were implicitly in communion with His Church. This raises the question of whether others too – even in our times – could be saved through implicit faith. The Church does not hurry her deliberations about such questions. However, because of the mercy of God, some version of the “Yes” answer seems increasingly plausible to most Catholic thinkers. As we see in the interview, these thinkers include the Pope Emeritus, Benedict XVI. Yet the possibility that implicit faith might suffice for salvation provokes several subsidiary questions. One, of course, is what would count as placing one’s faith implicitly in Christ. Another is why – if implicit faith might suffice -- evangelization is necessary at all. Let’s take these up one at a time. As to the first: Although the answer is far from clear, at least something can be said about what would not suffice for salvation. For example, Benedict rejects the “anonymous Christian” hypothesis offered by the theologian Karl Rahner, according to which placing one’s faith implicitly in Christ involves no more than subjectively accepting one’s self, or perhaps making some kind of existential choice for good over evil. Why was Rahner wrong? One reason seems to be that no one chooses against himself as such. It is one thing for me to be for myself as what I really am, a child of God made in His image, but as Benedict suggests, it is another for me to be for whatever I take myself to be. Even Satan was “for himself” in this distorted sense. A second reason is that no one chooses evil as such. In fact, no one commits any sin except for the sake of something he considers good, but this does not make sin itself good. A third reason is that Rahner’s answer does not seem to require conversion or change of heart, with all this implies about acknowledging one’s sinfulness and one’s inability to save himself. One listens in vain for Rahner’s “anonymous Christian” to cry out like the man in the Temple, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” Benedict mentions a fourth reason too, which is very profound. As he points out, the theologian Henri de Lubac emphasized that following Christ involves becoming conformed to Him in His loving sacrifice. This is why, as Christ said, we must take up our own crosses too. Then is what Christ did for us not enough? No, the reason we must be joined to what He did is precisely that it is enough. We are saved by the Atonement; therefore we must be united, somehow, with the Atonement. Let’s turn to the second subsidiary question: Why is evangelization necessary at all? Christ and the Apostles considered preaching the gospel a matter of life and death importance. Yet if even implicit faith in Christ might suffice for salvation, why must people be told? Although Benedict does not consider possible answers to the question, he says further reflection is needed on all these issues, so perhaps even a non-theologian like me may dare to offer a thought. For it seems to me that every serious Christian knows a small part of the answer. We know by our experience of following Christ that taking up our crosses is difficult even if we do know who Christ is. Yes, just as He said, His yoke is easy and His burden light -- but this is true only because He provides grace sufficient for the task. The way of the person whose faith in Christ is merely implicit will be precarious and difficult, because he does not know about that grace, and does not know where to find the channels through which it pours. For example, suppose such a person falls into grave sin. Obviously he needs to repent, but complete repentance involves being sorry not just for fear of the consequences of sin, but for the very love of God. Consider how difficult this would be for him, considering that what makes grave sin so grave is precisely that it destroys that bond of love. How badly he needs the help of the sacrament of reconciliation, but he does not even know such help exists. Consider too that it would be more difficult for him to recognize his sins in the first place. There are some general principles about right and wrong that everyone really knows deep down, but it is quite another things to be honest with ourselves about them, and we need to be confronted. There are also more detailed matters of right and wrong, which are difficult to work out, and we need to be instructed in order to understand them. Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and pastoral care do confront and instruct us. I am not here thinking of a person who knows of these things but neglects them, for a person who rejects the things of faith certainly cannot be said to have implicit faith. Rather I am thinking of someone who would accept them if they were made known to him, but he has never heard of them. The fact remains that he does not have their assistance. So it is one thing for salvation through merely implicit faith to be possible, but it is quite another for it to be easy. Implicit faith in Christ desperately needs to develop into explicit faith in Christ. This requires knowledge, and knowledge requires evangelization. This is why Isaiah and St. Paul cry, “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!” I asked, in a follow-up to your letter, whether you had read the C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories, which are admired by Protestants as well as Catholics. The reason is that there is a fascinating scene in The Last Battle which illustrates the possibility – but difficulty -- of implicit faith in Christ. Emmeth, the worshipper of the false god Tash, has come to a place which might be called the vestibule of heaven. Meeting there several followers of the great lion, Aslan – who is Christ as he appears in Narnia – Emmeth tells them his story: "I looked about me and saw the sky and the wide lands, and smelled the sweetness. And I said, By the Gods, this is a pleasant place: it may be that I am come into the country of Tash. And I began to journey into the strange country and to seek him. "So I went over much grass and many flowers and among all kinds of wholesome and delectable trees till lo! in a narrow place between two rocks there came to meet me a great Lion. The speed of him was like the ostrich, and his size was an elephant's; his hair was like pure gold and the brightness of his eyes like gold that is liquid in the furnace. He was more terrible than the Flaming Mountain of Lagour, and in beauty he surpassed all that is in the world even as the rose in bloom surpasses the dust of the desert. Then I fell at his feet and thought, Surely this is the hour of death, for the Lion (who is worthy of all honour) will know that I have served Tash all my days and not him. Nevertheless, it is better to see the Lion and die than to be Tisroc of the world and live and not to have seen him. But the Glorious One bent down his golden head and touched my forehead with his tongue and said, Son, thou art welcome. But I said, Alas, Lord, I am no son of thine but the servant of Tash. He answered, Child, all the service thou hast done to Tash, I account as service done to me. Then by reasons of my great desire for wisdom and understanding, I overcame my fear and questioned the Glorious One and said, Lord, is it then true, as the Ape said, that thou and Tash are one? The Lion growled so that the earth shook (but his wrath was not against me) and said, It is false. Not because he and I are one, but because we are opposites, I take to me the services which thou hast done to him. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him. Therefore if any man swear by Tash and keep his oath for the oath's sake, it is by me that he has truly sworn, though he know it not, and it is I who reward him. And if any man do a cruelty in my name, then, though he says the name Aslan, it is Tash whom he serves and by Tash his deed is accepted. Dost thou understand, Child? I said, Lord, thou knowest how much I understand. But I said also (for the truth constrained me), Yet I have been seeking Tash all my days. Beloved, said the Glorious One, unless thy desire had been for me thou wouldst not have sought so long and so truly. For all find what they truly seek. "Then he breathed upon me and took away the trembling from my limbs and caused me to stand upon my feet. And after that, he said not much, but that we should meet again, and I must go further up and further in.” So Emmeth could be saved by implicit faith in the true God; but eventually he had to meet Him in person, and go further up and further in. It might be protested that Emmeth did not meet the criteria suggested above. Maybe not. Still, I think this may be something like what the Pope Emeritus was suggesting in the interview.

|

SlippageSunday, 04-17-2016

Can everything we need to say about how to live be translated into rights talk? Possibly. But. Consider an easy case. I can translate the statement that parents have a duty to care for their children into the idea that children have a right to their parents’ care. Not bad. Now consider a harder case. I can translate the statement that we have a duty to seek the truth about God into the idea that we have a right to seek that truth, provided that we do not pursue it in ways that hinder the rights of those around us. Something is lost here. Surely our duty to seek the truth is based on our need for the truth. But as rational beings we need not only to seek it, but to find it, and not only to find it, but to order our lives in by it. Both of these things require the assistance of other people. Rights talk doesn’t have much room in it for the idea of a community of persons who order their shared life by the truth. Besides, which language we use has other ramifications. However firmly rights may be grounded in what is objectively just, they may seem to be subjective simply because they belong to individuals and need a subject to make a claim for them. Of course, the same might be said of duties, yet, psychologically, a difference exists. “My” duties in this sense direct my attention outward, to the persons toward whom I owe them. By contrast, “my” rights direct my attention inward, toward myself. This difference makes it very easy to view rights as though they were not really about objective moral realities, but “all about me” -- about the sheer assertion of my radically sovereign will. The upshot is that if rights talk is the only moral language that we know, there is going to be a lot of moral slippage.

|