The Underground Thomist

Blog

Holy ThursdayThursday, 03-24-2016

For not one member, but the whole entire body throughout was made an object of insolence; the head through the crown, and the reed, and the buffeting; the face, being spit upon; the cheeks, being smitten with the palms of the hands; the whole body by the stripes, by being wrapped in the robe, and by the pretended worship; the hand by the reed, which they gave him to hold instead of a sceptre; the mouth again by the offering of the vinegar. What could be more grievous than these things? What more insulting? ... Considering then all these things, control yourself. For what do you suffer like what your Lord suffered? Were you publicly insulted? But not like these things. Are you mocked? Yet not your whole body, not being thus scourged, and stripped. And even if you were buffeted, yet not like this. -- Chrysostom, Homily 87 on Matthew

|

The Merit of UnderstatementWednesday, 03-23-2016

Some people tell me that my book about the meaning of sex should have discussed disordered sex. I understand their view. What the old baptismal vows called “the glamour of evil” shimmers all around us, taking the word in its original sense of a deception or enchantment. But I don’t agree. The only way to get a bad thing is to take a good thing and ruin it. It follows that one understands the bad from what is good, not the good from what is bad. Once sexuality is understood, the problem with disordered sex becomes obvious, and the need to discuss diminishes. If one does so anyway, one may lose everything, because the jarring encounter with ugliness overshadows everything else. In this as in many things, there is a mean. There is a right time to discuss the misery and the shame of the bad. But not always. Not while discussing the joy and the glory of the good.

|

MistakesMonday, 03-21-2016

Question:Everyone makes mistakes and reconsiders. You’ve mentioned your own former errors and reconsiderations from time to time. What does a scholar – any scholar -- do about that sort of thing? Have you ever considered going over your past work and composing a book of second thoughts, like St. Augustine in his Retractationes or Corrections? Reply:The great Western saint wrote a book of second thoughts because his vast outpouring of thought had been important to so many people. A pipsqueak like me might want to write such a book – after all, even if only the occasional haunter of libraries comes across my mistakes, I don’t want to make him stumble. But if I did write one, no one would read it. Perhaps some day a scholar like me will be able to send abroad something like T-cells and macrophages, those useful critters in the immune system that seek out, engulf, and digest cells that aren’t behaving. A reader opens one of my early books to the beginning of Chapter 3. The paper begins to shrivel, and a warning voice intones, “Sir or madame. Please move your hands away from the page. The author has reconsidered and revised.” The shriveled page crumbles into dust, and a new one grows into its place, expressing what I would have said then if only I had known what I know now. I can’t do that, and it probably wouldn’t be a good idea anyway. What I can do is what you’ve noticed: When I reconsider an argument I have published previously, I can say so. When I talk about a previous book, I can mention its faults. When I discover something faulty in this blog, I can put it in order right away and advise readers of the change. For my penance, I try to do better, so that perhaps, if all goes well, I will leave behind some little thing worth knowing.

|

Why Tales Call Apples GoldenSunday, 03-20-2016

Since this is the day of rest, here is something I love from G.K. Chesterton: “[W]hen we are very young children we do not need fairy tales: we only need tales. Mere life is interesting enough. A child of seven is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door and saw a dragon. But a child of three is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door. Boys like romantic tales; but babies like realistic tales -- because they find them romantic. In fact, a baby is about the only person, I should think, to whom a modern realistic novel could be read without boring him. This proves that even nursery tales only echo an almost pre-natal leap of interest and amazement. These tales say that apples were golden only to refresh the forgotten moment when we found that they were green. They make rivers run with wine only to make us remember, for one wild moment, that they run with water. ... “All that we call common sense and rationality and practicality and positivism only means that for certain dead levels of our life we forget that we have forgotten. All that we call spirit and art and ecstacy only means that for one awful instant we remember that we forget.”

|

This Exceeds 140 CharactersSaturday, 03-19-2016

Wall Street Journal personal technology reporter Joanna Stern writes of Twitter, “You really can’t get the news faster or in greater breadth on any other social media platform.” Faster I get. Even breadth – every triviality is shouted from the rooftops. Don’t think much of the depth. Anyway, I’ve had that experience, thank you. It was called middle school.

|

The Problem with Changing All the NamesFriday, 03-18-2016

“Who is to say what marriage is?” Some find it discouraging that names can be changed. Yet isn't it encouraging that things don't change just because names do? You may go ahead and call cats dogs. But then we'll need a new word for the kind of dog that wags its tail and doesn't say "meow." They haven't become the same thing.

|

Hard ThingsWednesday, 03-16-2016

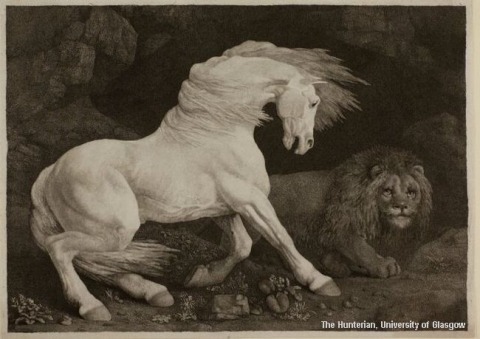

For a very ancient image of the right relation among the powers of the soul, picture a rider, a horse, and a lion. The rider sits tall in command; the horse swiftly and obediently carries him to his destination; and the lion assists him to overcome his obstacles and foes. Though horse and lion are on good terms not only with the man but also with each other, the lion is the nobler of the two beasts, urging on the horse in its exertions. The man is not the soul per se, but reason, which is the soul’s highest power – the one through which the “I” most clearly speaks. The horse is the soul’s power to stretch out toward what seems delightful. The lion signifies the ardor or fierceness by which it stretches out toward same goods, viewed as arduous or difficult of accomplishment. Reason is shown in the saddle because of his calling to be their master. His rule is a royal rather than despotical, because the subordinate powers are able to resist. Yet even someone who scarcely understands what royalty means may grasp that unruly things must be brought under royal rule and law. So much for the image in miniature. Now by opening it up into three different scenes, we get a glimpse of how such royal rule might be accomplished. In each scene, the man, the lion, and the horse stand in a different relationship. Scene one unfolds at night. A muddy road stretches out toward the eastern horizon, but the road is hard to see. In this scene the horse is not a horse, but a shaggy-eared ass, and the lion is not a lion, but a scrawny wildcat. In his right hand, the man is holding the ass’s reins, though he doesn’t seem to know what to do with them. In his left, he is holding a whip. The ass continually brays, “You had better feed me,” and whenever it does, the man obeys. All down the roadside he walks in search of things for the ass to eat. Every now and then, he thinks it might be more dignified to ride in the saddle, but whenever he tries to climb into it, the ass rears and plunges to dismount him, then drags him around by the reins. As he is being dragged, the wildcat bites him, yowling “Do as the ass says!” Sometimes he strikes back at the two animals with his whip. The ass, knowing that his mood will pass, sits down on its rump to wait him out. The wildcat cringes, but it is only cowed, not tamed. Eyes flaming with anger, it waits its chance to bite again. If anyone asks this poor man what he is doing, he says, “I’m pursuing my happiness.” In scene two, the man is still there, but the ass has become a brawny mule, and the wildcat a starving leopard. This time the man has some control over his animals, but his command is uncertain because they are more powerful than he is. Although he is seated on the mule’s back, trying to direct it down the highway, they are making little progress. Sometimes the mule turns off the road into pasture. At other times it stays on the road and perhaps even gallops, but as often as not, it runs in the wrong direction. Though the man uses whip, reins, and spurs, it detests being checked; twisting its head around to face him, it shows its blocky teeth and brays, “I haven’t yet lost my strength. You had better fear me.” But then the leopard snarls, punishing the mule by sinking its fangs into its flank. As the mule reverts to sullen obedience, the leopard gives the man dark looks and mutters, “I don’t know why I should be helping you.” The sun has risen, so the man can see the road, but he is ashamed to be seen because he looks so ridiculous. If anyone asks this poor man what he is doing, he says “I’m trying to be good.” In the final scene, the man is clad in knight’s armor, laughing and singing fighting songs. The mule has turned into a white stallion, and the leopard into a tawny, noble lion. Thunderously purring, the great cat sidles up to the knight’s knee and rumbles, “Where is the enemy? Command me!” Snorting and rearing, the stallion neighs, “Where may I carry you? Let me run!” The man guides the stallion with nothing but his knees and a few quiet words. In place of the whip, he carries a sword for making swift work of foes and barriers. Sometimes at a canter, sometimes at a gallop, the three of them head down the high road, straight toward the sun. Although that great orb is so bright that it ought to blind them, and so blazing that it ought to consume them, instead it gets into them like molten gold. If anyone asks the man where he is going, he answers “Toward joy.” As these three scenes tell the story, the desire for the delectable good and the desire for the arduous good are made to be ruled by intelligence, but desire can resist intelligence instead of obeying it. The loyalty of ardor in this contest is uncertain – on one hand it may side with the other appetite, but on the other hand it may side with intelligence, for as we know, a man can become just as angry and ashamed with himself for trying to exert self-control as for not exerting it. Even when ardor does side with intelligence, it may do so resentfully, like a slave, rather than loyally, like a servant. For all these reasons, the first efforts of someone attempting purity and self-command may seem ridiculous, not only to others but also to him. Nonetheless there is something lofty about these efforts, for it is better to try and fail than not to try. Though it may seem at times as though the whole matter were nothing but a mass of difficult rules, the rules themselves are made for a great and beautiful reason, for removal of the obstacles that keep the soul from riding swiftly to the sun and becoming as resplendent as it is. A word against overstatement. Very few of us in this life seem much like molten gold. Even those who reject the first scene are more like the second than they would wish. Progress down the road is measured not in miles but in inches. Even so, it is measurable. Our efforts become less and less ridiculous; we begin to catch the golden scent of the burning sun even when still far from it. Siegeworks that once would have stopped us, we begin to be able to scale. About those mightier barriers that still exceed our strength, there are rumors of help from the Emperor; but these reach our ears not from natural law, but from Divine.

|