The Underground Thomist

Blog

When to Stop TalkingSaturday, 02-20-2016

A common view has it that we have a moral duty to talk with everyone – that unless we are constantly in dialogue, we are both unreasonable and uncharitable. On the contrary, sometimes both charity and reason require breaking off conversation. Or even refusing to enter it. Recently a woman wrote because – she said – she had questions about the Church. I answered them. She then became personally insulting and claimed that I was lying. I said that I thought she was too angry for a continuation of the exchange to be helpful, and that it grieved me to see her deceive herself about wanting to engage in dialogue. On another occasion a young man approached me because – he said -- he wanted to learn to debate sexual hedonism better against people like me. I told him that if his mind was open, I would be glad to discuss whether his philosophy was true, but I was not interested in helping him sharpen his debating technique. Just what motive is operating in a given conversation may be difficult to discern. To someone who rattles off a great many questions without listening to the answers, I sometimes put the question, “Would it make any difference to you what the answers were?” You may be surprised by how many people reply “No.” At least that’s honest. Here is one way to respond: “Then let’s not waste time with all that. Can you think of something you really want to know?”

|

The Low in the Service of the LovelyFriday, 02-19-2016

I blogged the other day about the idea of the fitting, or appropriate. One of the paradoxes of the fitting is that there is a place even for ugliness – not for its own sake, but to resensitize our jaded minds to the unfitting. The classical model for this is the gross style adopted by Dante Alighieri in his Inferno, so different from the styles of the other two canticles of the Comedy. A good contemporary example of this paradox is a fine piece by Anthony Esolen, who writes “We live in an age of phantasmagorical masks, vandalizing the second most beautiful thing in physical existence, the body, and turning into the ego’s billboard the most beautiful thing in physical existence, the thing that the blind Milton longed most to see again -- the human face divine. In emphasis, it is as if the abdomen or the crotch or the bosom were what we thought made us most ourselves; as if we were walking and talking groins, with stunted little countenances hidden away below.” Such ugly images are not to be too often conjured. Here, they work, for Esolen, who loves loveliness, knows when an arresting and finely calibrated crudity in words is the only thing that will serve to break through our hardened indifference to crudity in fact – when it is just enough to jolt us about what ought to jolt us, but doesn’t. Then again, he is a Dante scholar.

|

Who, Me?Thursday, 02-18-2016

A reader comments:Your blog is not only enjoyable, but has also led to repentance. Many at church here, including me, have had to examine themselves after reading your piece “The New Evangelization and the Old Excuse.” Thank you for this convicting post. Reply:Thank you. If I know anything about self-deception, it is only because I have spent so much time deceiving myself. No one learns anything from self-deception per se, but one can learn plenty from being caught at it.

|

Chip by ChipWednesday, 02-17-2016

In teaching classical works of ethics – say, Cicero’s On Duties -- one of the most difficult things to explain is the idea of the fitting. Our ancestors considered it obvious to any decent mind that some things are rationally appropriate to a given situation, and others are not. Instead, we take notions of what is fitting to be nothing but “manners.” It’s even difficult to explain the difference between the two views, because today the term “manners” is also misunderstood. To us it refers to arbitrary conventions which do nothing but infringe on our liberty. We tell ourselves that the Chinese have one kind of manners, the Canadians another, and the Hottentots another still – just what we tell ourselves about morality. The fact that universal ideas of courtesy and gratitude underlie all these differences is lost on us. Chip by chip, like mosaics, all these obvious, forgotten things must be restored.

|

The Paradox of Justice ScaliaTuesday, 02-16-2016

Question:Apropos the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, the non-Catholic religion reporter Terry Mattingly comments, “I would … have liked to have seen someone talk to Catholic scholars about the degree to which 'natural law' did or did not influence” him. A lawyer, not a scholar, I am not sufficiently knowledgeable about Scalia's views on the natural law to know the answer. Do you have any thoughts on this? Reply:Justice Scalia was a paradox. He believed in natural law; it was part of his Catholic faith. However, he took his judicial oath to mean that he must uphold the “positive” or enacted law, or, if he was conscientiously unable to do so, resign. Needless to say, the natural law does not allow vows to be set aside casually. The Justice took his oath to imply that judges must not allow the natural law to enter into their reasoning about how cases should be decided. Nothing mattered but what the enacted law actually meant. For judges to consider the natural law would in his view be a form of judicial activism, an unauthorized usurpation of the trust committed to legislatures and constitutional conventions. Natural law thinkers agree that the judicial office does not authorize judges to rewrite laws and constitutions by judicial fiat. However, in their view it does not follow that judges may not consider the natural law, because no formula of words is entirely self-interpreting. Consequently, no matter how determined one is to defer to the enacted law, one must consider the natural law just to know what it means. So legislators must rely on natural law in order to enact the positive law, but judges must rely on natural law in order to understand it. The words which humans use presuppose the law written on the human heart; they cannot help doing so. I will always remember Justice Scalia for his great generosity in speaking to a seminar on natural law which I led for six weeks at Calvin College in 2003. The judge gave us an entire day, submitting to our questions for three full hours, sharing a working lunch with us for another hour and half, then giving a semi-public lecture, followed by yet more questions. He will be missed.

|

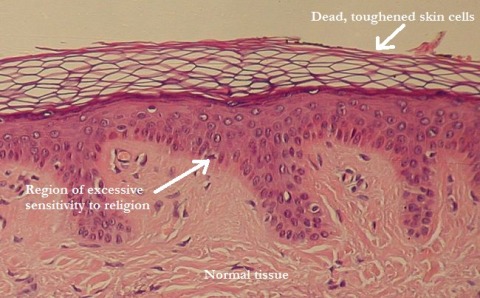

Thick Descriptions, Thin SkinsMonday, 02-15-2016

A reader responds:Your recent remarks about anti-Christian bias in graduate school (here, here, and here) are only too true. In case you haven’t seen it already, you may be interested in So Many Christians, So Few Lions, by sociologists George Yancey and David Williamson, which confirms this fact in great detail. What they find – I have read the book, but I am quoting from a newspaper interview with one of the authors -- is that an elite subculture of persons who are highly educated, white, wealthy, not highly religious, and self-identified as moral “progressives” views Christians as “ignorant, intolerant and stupid individuals who are unable to think for themselves ... a backward, non-critical thinking, child-like people who do not like science and want to interfere with the lives of everyone else.” The book also validates the experience of Christians who encounter anti-religious bigotry. There is a tendency, even among Christians, to minimize reports of those who do experience hostility. I recall one Christian commenting on a movie which follows the experience of a college freshman who encounters blatant and dogmatic attacks on his faith from his philosophy professor. Her comment was, “The premise is so lame. That does not happen.” It really does happen, and is not merely accidental to academic life. It happened to me during my own graduate studies. I remember the day when I was shocked speechless by hostile, off-the-wall remarks directed my way by my anthropology professor. Fortunately, the teaching assistant, who was Jewish, took up for me and redeemed the day. In your reply to my previous letter, you asked what triggered the attack. I am not really sure, but I had suggested in class that the methodology of “thick description,” promoted by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz, would allow consideration of the influence of religion on culture. The professor ranted that she would not allow religion to be brought into the classroom – as though I had been preaching. I checked my perceptions with another grad student who affirmed, "Yeah, she was picking on you." She was more aggressive toward me than toward any other student the whole semester. Even so, after a year of study, she seemed glad to see me around and always greeted me in the anthropology office. So, after some initial hazing, I may have earned respect. Reply:I hear about hazing from quite a few Christian grad students. Sometimes it comes only at the beginning, sometimes it continues. You earned respect because you were courteous but didn’t back down, even though, on that first occasion, you were too stunned to reply. Students who think they are being hazed should do just as you did, checking their perceptions with others in the class. Professors are supposed to be tough, and sometimes students may think they are being hazed when they aren’t. Not only religious students, but also anti-religious students may acquire that false perception. In my own experience, Christian students are more likely than atheists to keep silent for fear of being attacked by the professor – but atheists are more thin-skinned, even when the criticism is fair and well-intended, because they are not used to having their assumptions challenged. A group of former grad students I know used to run intellectual relays. Each time one of them began to tire under their professor’s relentless criticisms, another would take the baton and run with it. They came to enjoy the game, and so did the other students. The professor, who called them the “amen corner,” would actually invite them to speak up in seminar, because they were always prepared, their reasoning was always careful, and they always had interesting things to say. That’s the way to capture strongholds.

|

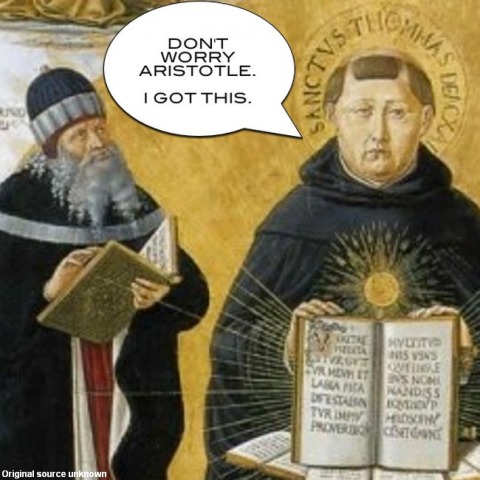

A Thomist TrailerSunday, 02-14-2016

The Commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on Law now has its own trailer: What is law? Is there such a thing as natural law? Where does it come from? What does it demand of us? What does it imply about human laws? Talk it up. Link to it on Spacebook. Print the web address on your tee shirt. Send your friends Treatise on Law greeting cards. Wouldn’t it be fun if this 76-second epic spread further? I would like to thank all the volunteers who donated their time, not only those who had speaking parts, but also my friend, Arlen Nydam, the videographer. All I did was write a 157-word script and schedule a few people. Check out his beautiful website. Other links:The Underground Thomist YouTube ChannelThe Underground Thomist Listen to Talks Page

|