The Underground Thomist

Blog

ParadoxSaturday, 02-27-2016

The Wisdom books present some surprises – among them, a fair sampling of paradox. Take for example the book of Proverbs, which includes a number of apparently inconsistent sayings colliding head to head. This pair is from Chapter 26: Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest you be like him yourself. Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes. “See? The holy literature of the Christians contradicts itself!” But no. Such juxtapositions are deliberate. There really are reasons to confront fools on their own terms, and there really are reasons not to. To know when to speak and be silent, one must weigh the reasons case by case. One who has not meditated on this vexing fact will hardly have grasped what the craft of rhetoric is for.

|

Conscience Does Not Care What We AssumeFriday, 02-26-2016

It may seem that the possibility of forgiveness matters only on the assumption that there is, in fact, a God -- that without the lawgiver, there would be no law, and therefore nothing to be forgiven. The actual state of affairs is more dreadful, for the Furies of conscience do not wait upon our assumptions. One who acknowledges the Furies but denies the God who appointed them -- who supposes that there can be a law without a lawgiver -- must suppose that forgiveness is both necessary and impossible. That which is not personal cannot forgive; morality “by itself” has a heart of rock. And so although grace would be unthinkable, the ache for it would keen on, like a cry in a deserted street. |

Resisting Tyrannical GovernmentsThursday, 02-25-2016

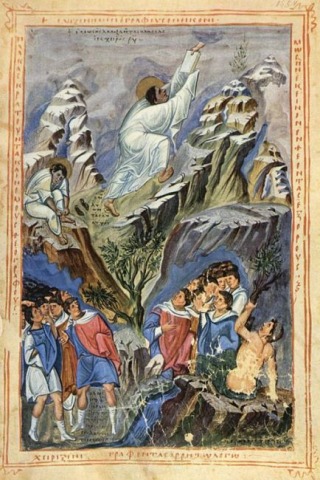

Some time ago, after I blogged about civil disobedience to unjust laws, several readers asked me to blog about a related question: How should one respond if the government itself becomes tyrannical? You will not be surprised that I follow St. Thomas Aquinas’s analysis -- rather than, say, John Locke’s or Karl Marx’s. The best thing to do, of course, is to take care that the government does not become tyrannical. One thing this requires is a good and balanced governmental structure which recognizes the principle of rule by law; the other is virtue, both on the part of the citizens and on the part of the rulers, for otherwise even the best constitution is mere drapery. But what should be done if despite all precautions, the government does degenerate into tyranny The answer depends on what kind of tyranny it is. Extreme, energetic tyranny is the worst possible kind of rule, for the ruler actually attacks the common good. Everyday, lazy tyranny is not as bad, for the ruler merely neglects it. If the tyranny is of the everyday sort, St. Thomas thinks it is better to tolerate it than resist it, because still worse evils threaten no matter how the resistance turns out. For if the resistance fails, it may provoke the ruler to rage and turn into the extreme sort of tyrant; it it succeeds, the most probable result is rule by competing selfish factions, and this state of affairs usually ends with the leader of one of the factions seizing the tyranny for himself. The new tyrant is likely to be much harsher than the old one, if for no other reason than that he fears to suffer the same fate. What if the tyranny is of the extreme sort? For that case, St. Thomas does propose resistance, but he insists that it be carried out constitutionally, by public authority rather than by private presumption. Presumably, the constitutional traditions of various countries may provide various ways to depose a tyrant. By way of example, St. Thomas considers only one such case, in which the assemblies of the people have the constitutional authority not only to appoint the king, but also, by implication, to remove him. Needless to say, the tyrant will probably seek to block any attempt to remove him, for example by preventing the assemblies of the people from meeting. In some constitutional arrangements, further appeal is possible. On the other hand, in an empire, one can appeal against the tyrant to the emperor. Probably St. Thomas would consider all of the sorts of things we call federations empires, so a close parallel to “appeal to the emperor” would be the provision in the U.S. Constitution that allows any state to appeal to the federal government for a restoration of republican rule. What if constitutional resistance fails? Then would it become permissible for private individuals to take matters into their own hands? For instance, might they attempt tyrannicide? No. St. Thomas does take the idea seriously, conceding that at first there even seems to be biblical precedent in Ehud’s slaying of the Moabite king Eglon. In the end, however, St. Thomas rejects tyrannicide. Among other things he points out that the killing of Ehud was not actually a tyrannicide, but an act of war; Ehud was not acting as a private individual, but as a soldier under the authority of the nation of Israel in its just war against the invader. This raises an interesting possibility that St. Thomas does not discuss in On Kingship, but that would seem to be permitted by his analysis of just war. Among the just causes of war, he claims, are are “securing peace,” “punishing evil-doers,” and “uplifting the good.” Suppose, then, that for just such reasons as these, other nations declare a just war against the tyrant, and a member of the tyrannized country acts under their commission to kill him. Assuming that all the other conditions of just war are fulfilled, then his act would be permissible for the same reason that Ehud’s was. It would not be an act of private presumption but of public authority. St. Thomas gives two other reasons for rejecting vigilantism, one of them theological, the other philosophical. The theological reason is that it contradicts Apostolic teaching; the philosophical reason is that it is imprudent. Why is it imprudent? Because if the assassination of undesired rulers by private presumption were an option, then it would more often be seized by wicked men to slay good kings, than by good men to slay tyrants. This warning would seem to concern not only solitary rebels, but also rebel armies. Suppose the rebels claim to represent the people as a whole; after all, St. Thomas does hold that a morally competent people should be ruled with their consent. Although he does not discuss this possibility that rebels might make such a claim, the tenor of his argument suggests that he would not be impressed with it. Many competing groups may claim to represent the people as a whole; that does not mean that they do. Besides, he has already explained that factional conflict tends to produce tyrannies even more bitter than those it sweeps away. So if both national and extranational public authority fails to remove the tyrant, then, barring vigilante actions that would make matters still worse, there is nothing left but to pray – something one should have been doing from the start. “To pray?” we think. “How ridiculous.” But St. Thomas thinks it is very practical. Tyranny is unlikely to arise among a virtuous people; if it does arise, they have probably been softened and prepared for it by a long period of moral decay. Until things get very bad indeed, they may even like tyranny, either because the regime has given certain constituencies private benefits, because most citizens have not yet been personally hurt, or because the desires of the people are so disordered that they do not clearly see their own condition. God does not often protect people from the natural consequences of their corruption; He more often allows these consequences to ensue in order to bring corrupt nations to their senses. If at last the people do repent and mend their ways, then God will hear their prayers, but St. Thomas warns that “to deserve to secure this benefit from God, the people must desist from sin, for it is by divine permission that wicked men receive power to rule as a punishment for sin.” Interestingly, the need to couple resistance to tyranny with repentance, prayer, and moral reform was a major theme of colonial preaching during the American quest for independence, though whether the revolution fulfilled St. Thomas’s criteria for resistance – or even Locke’s -- might well be questioned.

|

Christian Hedonism?Wednesday, 02-24-2016

Question:I am drawn to the works of John Piper, the self-described “Christian hedonist,” and so it was with great interest that I read your post about hedonism. Now, to Piper the word “hedonism” simply means the pursuit of pleasure. He defines pleasure quite expansively — to include deep, profound sensations of joy that can be experienced even in the midst of great physical or emotional pain. Indeed, he emphasizes that the “pleasure” that we are to pursue as Christian hedonists is first and foremost this deep-seated joy no matter how greatly it may seem to war against our natural senses. Additionally, he emphasizes the eternal nature of our quest -- that we want pleasure forever and not merely today, so we shouldn’t do things today that put our eternal reward at risk. With that being said, I am left scratching my head about how, if at all, your criticism of hedonism would apply to him. Reply:Since I am not closely familiar with the works of John Piper, rather than criticizing the gentleman let me proceed from first principles. Yes: Hedonism is the doctrine that the supreme good is pleasure. Thus understood, hedonism is incompatible with Christianity. If an ethic is really Christian, then it can’t be hedonistic; but if it is really hedonistic, then it can’t be Christian. But why isn’t hedonism Christian? The issue is how pleasure is related to happiness. We are naturally directed to our good. This is how the Creator made us. So of course you want to be happy. But is happiness just pleasure? No. Happiness is an activity: Not something we are feeling, but something we are doing. The activity for which we were ultimately made is to know God: To gaze upon Him face to face, completely immersed in seeing Him as He Is, not with the eyes of the body, but with the mind. The happiness which is possible in this life is but a glimpse or reflection of that final happiness with Him which leaves nothing to be desired. The attainment of the beatific vision far exceeds our natural powers, but in heaven, the blessed will be supernaturally lifted beyond them. If I might be permitted a short digression, I would add that this very longing to see God is the basis of one of the proofs of His existence. Since for every natural longing there is something that quenches it, and since there is one natural longing which cannot be quenched by anything in creation, its satisfaction must lie beyond creation. Thus it lies in the Creator; thus He exists. To resume the thread of the story, we naturally desire our final happiness, which is perfect, sufficient, and delightful. Consequently, the only way anything can attract us is through the promise – in some cases, the delusory promise – of sharing in at least one of these qualities. Since happiness must have perfection, distinction and eminence seem good to us; since happiness must have sufficiency, we strive to acquire wealth enough for our needs and the needs of those committed to our care; and since happiness must be delightful, we seek pleasure. The problem lies in slicing one of these qualities of happiness off from the rest and pursuing it for its own sake -- apart from the guidance of reason, apart from consideration for our final good. The cardinal vices provide fine examples, for the proud and vainglorious take a misguided and excessive interest in eminence; the greedy and avaricious, in wealth; and the lustful and gluttonous, in the pleasures of the body. But there are a thousand varieties of this sort of thing. Stoics are haunted by the desire for perfect control; valetudinarians, for perfect health; fashion queens, for perfect beauty. Materialists are consumed by getting, keeping, and having what is never quite enough, whether of money, automobiles, or even unread books. And there are an infinite number of hedonisms, each fixated on some kind of pleasure -- of the flesh, of the eye, or even of the soul, of the sheer delight of being caught up in spiritual excitement. That used to be recognized as a heresy. The problem with hedonism, then, is the same as the problem with each of these. They are all cases of mistaken identification – of confusing the properties of happiness with happiness. It is one thing to say that the ultimate good is delightful; it is quite another to say that delight is the ultimate good.

|

The Threshold of JudgmentTuesday, 02-23-2016

One wonders what so-called values voters in the recent South Carolina primary thought they were doing. Apparently the wrong “values” were in play. Some were repelled by the ugly character of the winning candidate; most weren’t. The fundamental problem is that above a certain threshold of moral and practical judgment, people prefer rulers who are better than themselves -- but when they fall below it, they begin to prefer rulers who are worse than themselves. A significant proportion of the voting public now falls below that threshold. In the first place, they fall too easily for the view that bad men can be good statesmen. “He may be a thug,” they reason, “but thugs get things done.” What kinds of things? Whatever they want. For example, some see the candidate as a businessman who will dismantle big government. In fact, like most of our big business class, he is a crony capitalist who loves big government and its favors. In the second place, they don't see him as a bad man. They view him as a strong man, because he boasts and bullies – and as a smart man, because he has money and breaks the rules. In the third place, they find brutishness magnetic. We see this in private life; some women feel safer with men who beat them up, and some men feel stronger in the company of men who dominate them. The same drives operate in politics. Finally they want a savior: If not a Son of God, then a son of the devil. They hunger for a cure for "this world of troubles," for a machete heavy and sharp enough to cut through all the dark vines in the jungle.

|

TheonomyMonday, 02-22-2016

Question:Thanks for your Commentary on Thomas Aquinas's Treatise on Law. I know you touched on “theonomy” (as in Old Testament civil law for today) in there, but is there any more you can say about it? It's becoming very popular in [certain Protestant circles].” Reply:That’s a good question, but I think we are using the same word for very different things. Let’s see if we can get this straightened out. I’ve edited out the names of specific groups and individuals, but in the ultraconservative Calvinist circles you mention, “theonomy” is a buzzword for applying Old Testament law to contemporary society, just as you say. This is a mistake, because Old Testament law was never intended as a blueprint for all societies. In fact, it wasn’t even meant to be a permanent blueprint for the Hebrew people; it was a civil code, yes, but also a schoolmaster or teaching tool. Christ pointed out, for example, that the Old Testament law merely limited revenge by means of the precept “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” This was good, but God’s ultimate intention was to put an end to revenge. Thus, the underlying moral principles of Old Testament law, such as punishment for those who do evil and honor for those who do well, are universally valid, and these are precepts of the natural law. But the implementation of these precepts in the Old Testament is not universally valid. Some of the “theonomists” you mention might agree with me in part, because they say they do not want to apply Old Testament law literally, but only to apply what they call “the equity of the law,” meaning just those underlying principles I have mentioned. If this approach to Old Testament law were fully implemented, then I think it would flower in a complete doctrine of natural law. This hasn’t happened, because, unfortunately, many of these “theonomists” reject natural law altogether. They argue that because human nature is fallen, no one can know anything about right and wrong except from the Bible. This denial of natural law in favor of the Bible is not only mistaken, but it is contradicted by the Bible itself, which makes clear that although our nature is fallen, it is not destroyed, and that although the “law written on the heart” may be overwritten, it cannot be erased. By the way, Calvin agreed with me about this; he wrote that the view that our nature has been destroyed is not Christian, but Manichean. When I used the term “theonomy” I was using it in a different sense – in the sense of John Paul II, who wrote in Veritas Splendor (“The Splendor of Truth”) as follows. Notice that he modifies the term, making it “participated” economy. In part, this echoed Thomas Aquinas, who called the natural law the mode in which the mind of the rational creature “participates” in the law in the mind of God. It was also a response to those who mistakenly think obedience to God is a kind of “heteronomy,” something imposed on man from outside. Thus the Pope writes, “Others speak, and rightly so, of theonomy, or participated theonomy, since man's free obedience to God's law effectively implies that human reason and human will participate in God's wisdom and providence. By forbidding man to ‘eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil’, God makes it clear that man does not originally possess such ‘knowledge’ as something properly his own, but only participates in it by the light of natural reason and of Divine Revelation, which manifest to him the requirements and the promptings of eternal wisdom. Law must therefore be considered an expression of divine wisdom: by submitting to the law, freedom submits to the truth of creation. Consequently one must acknowledge in the freedom of the human person the image and the nearness of God, who is present in all (cf. Eph 4:6). But one must likewise acknowledge the majesty of the God of the universe and revere the holiness of the law of God, who is infinitely transcendent: Deus semper maior.” Here is what I wrote in part of my book that you must have read: “Law is an extrinsic principle of acts because it is promulgated by God, and in this sense comes from outside us. However, in another sense it is inside us, for it finds an echo in our own created being; natural law is the ‘participation’ of the rational creature in the eternal law. For this reason, obedience to God’s law in no way diminishes human freedom. On the contrary, being made in His image, we are most true to ourselves precisely when we are most true to Him. This also shows that when Immanuel Kant distinguished between autonomy, or self-legislation, and heteronomy, or passive subjection to the law of another, he was posing a false alternative. To use an expression of John Paul II, the human sort of freedom is a third kind of thing, a ‘participated theonomy.’” I added later: “The doctrine of the inviolability of conscience is often confused with the doctrine of moral autonomy. In reality, no two things could be further apart. According to those who hold the former doctrine, my freedom lies in my willing participation in a law that I did not make, but that I see with my mind to be right. But those who hold the latter view believe that I myself originate the law. Consequently, they view my freedom as consent to nothing but my own will. A person who holds the doctrine of the inviolability of conscience recognizes the dreadful possibility of an erring conscience, but a person who holds the doctrine of moral autonomy cannot see how the individual could really err, as he originates the law that he obeys; there is no ‘external’ standard by which he could be held to be mistaken. To him it seems that obedience to God is just as much slavery as obedience to the lowest earthly tyrant, for in both cases I submit to something that is alien to myself. “Those words, ‘external’ and ‘alien,’ are the crux. Is God really alien? Is His standard really external? According to St. Thomas, no, because my whole God-given being resonates with God inwardly. Natural law is the mode in which I share in the eternal law as a rational creature. “To put it another way, the proponents of the doctrine of moral autonomy recognize but two alternatives. Heteronomy, or obedience to an alien ‘other,’ they view as slavery; autonomy, or obedience to myself, they view as freedom. But St. Thomas recognizes three alternatives. Heteronomy, or obedience to an alien ‘other,’ is certainly slavery. Autonomy, or obedience to myself in alienation from God, is still slavery because it is disguised heteronomy. For since I am made in God’s image, if I am alienated from Him, then I am also alienated from myself. Obedience to my alienated self is but obedience to yet another alien ‘other.’ The only true freedom is ‘participated theonomy,’ joyful participation in the law of the God in whose image I am made. Only in this way can I be fully what I am; and so only in this way can I be fully and truly free.” In using the term “participated theonomy,” then, John Paul II was speaking to at least two groups. First he was speaking to theologians, who recognized the term “participated” from Thomas Aquinas’s definition of natural law. Second he was speaking to philosophers, who recognized the terms “autonomy” and “heteronomy” from Immanuel Kant. But some of us think John Paul II was trying to speak to a third group as well. By using the term “theonomy,” but modifying it, he may have been engaging in a cautious, respectful bit of ecumenical diplomacy with Protestants, inviting them to join in the ongoing dialogue about natural law. The Church has wanted that to happen for a long, long time.

|

CheerfulnessSunday, 02-21-2016

Among the cruelest slaveries is mood, because we recognize neither the master nor the manacle. In the first place we don’t notice our moods; in the second place we don’t notice that they have mastered us. The first step toward freedom from this tyrant is to see him. This step is often the most difficult; my mood will usually be plain to everyone else long before it is visible to me. The second step toward freedom is to defy him. I may feel foul; it does not follow that I must do his bidding and act foully. The third step is to break the shackle. Although it is not easy to change a mood, it is often much easier than we expect, even when we are in affliction. The last and most difficult step is not to be caught again. I must not to venture into the alleys and culs de sac where my known foul moods hide out; I must carry my weapons lest they leap out unexpected; I must practice the martial art of being cheerful.

|