The Underground Thomist

Blog

Peter RabbitMonday, 03-07-2016

Question:In The Line Through the Heart you remind your readers that “A truly adequate theory of the natural law will not always be turning into metatheory of the natural law, a theory about theories. It will resist that tendency.” But you also comment about why that tendency is so pervasive. We quarrel about natural law not because it isn’t obvious, but because we don’t like it. Instead of trying to understand how we are made, we waste time pretending that we aren’t really made that way. What I think you’ve just described is an apologetics problem, and I face it all the time. I struggle with how to reply and interact with those for whom conversation seems to so quickly turn into the game that someone has called "Everything you can do I can do meta." Pick a meta -- any meta. Could you suggest questions I could use to suggest to my friends that one's epistemology ought to be the handmaiden of what we know, instead of a way to deny what we know? Reply:You may have in mind a conversation about the natural law itself, and in another post I’ve given an example of that sort of thing. But I think you have in mind something different – the Peter Rabbit game in which you ask a concrete moral question about, say, abortion, marriage, or euthanasia, and instead of answering it, and your friend, casting you in the role of Mr. McGregor, hides under the flower pot of metaquestions: “How do we know whether anything is right?” “Who is to say what the nature of anything is?” Don’t misunderstand me: Such questions are important. But the proper place of such questions is to help find things out, not to run away from finding them out -- to become wise, rather than exercise our cleverness. First, then, here’s how not to respond when someone hides in the flower pot. Don’t open a discussion of how epistemology ought to be the handmaiden of what we know. You’re right – it should be -- but you’re playing the other fellow’s game. He retreated from questions to metaquestions, and you’ve responded by retreating from metaquestions to meta-metaquestions. The obvious move for him now is to pose a meta-meta-metaquestion. “You say P is the handmaiden of Q, but how are we to decide the priority of one inquiry to another?” You see? You are trapped in an infinite regress. So when your friend tries to jump into the flower pot, don’t follow him. Instead, grab his ankle and pull him back out to the original question. He will either allow himself to be pulled back, or he won’t. If he does allow himself to be pulled back, then you discuss the question. If he doesn’t, then he forfeits -- and you have to make that clear. For example: You: “So are you saying that taking the lives of unborn babies is morally right?” Him: “Ah, but that is the question, isn’t it? What is a baby?” You: “Are you saying that since you don’t know what babies are, killing them should be allowed?” Him: “Who am I to say what should be allowed? Who is anyone to say what a baby is?” You: “Have you noticed that you aren’t answering my questions?” Him: “I am trying to point out that many, many other questions would have to be answered before I could answer your question.” You: “I propose that while we are engaging in that interminable inquiry, we let the babies live. Do you agree?” Him: “That raises an interesting quandary about the epistemological requirements of practical decision.” You: “Let’s suspend our discussion of the abortion question until some time when you are actually willing to answer it. In the meantime, you have my own answer: Let them live.”

|

Back Seat of a CadillacSunday, 03-06-2016

Slightly revised; thanks to alert readersQuestion:For what it's worth, even as a Protestant, I have found the fruit of your defense of the natural law invaluable. Here is my question. If we consider marriage merely as a natural reality, prescinding from its sacramental aspects, would two amorous teenagers in the backseat of a Cadillac promising to "love each other forever" create a marriage in God's eyes? It seems to me that there must be certain conditions for a valid marital promise to be made, and these include things that the state requires for the recognition of a marriage, like witnesses and legally binding statements. Reply:Thank you. You’re right – there is no marriage here. Let's sort this out. First a distinction between the castle and the gate that we enter it by: Matrimony is the status of being married, a status which carries with it certain rights and duties that cannot be changed by the will of the parties; if they do not acknowledge them, then although they are in some sort of relationship, they are not in the status of matrimony. Marriage is the act of entering that status. Now, a distinction about matrimony itself. There is only one species of marriage, but natural matrimony may also be civil or sacramental. Natural matrimony is a complete partnership of life between a man and women, directed by its very nature toward both their own good and the procreation and care of their children. Notice that if the man and woman do not intend a procreative partnership, they are not married; they are merely in a sexual relationship. There are various other conditions too, both negative and positive; for example one cannot marry one’s sister. The act by which natural matrimony is entered is an irrevocable covenant, a free and mutual promise to accept each other for life as husband and wife. Civil matrimony is – or ought to be -- natural matrimony which has been recognized by the state so that doubts about the existence of the marriage are removed, the rights and duties of the parties can be enforced, and the vulnerable – especially the wife and children – can be more easily protected. Hence the state requires that the covenant must be publicly registered subject to the requirements of civil law. Canon law does something similar when it requires that for the man and woman to be married in the Church, their consent must be given before witnesses and an authorized minister. The travesty of civil marriage today is that the state claims that there is a marriage when by nature there isn’t one, and that there isn’t when by nature there is. That’s what happens when we put in office tyrants who deny natural law. Sacramental matrimony is natural matrimony which has been supernaturally lifted by the special grace of which it is the outward sign. Even apart from this grace, marriage is in principle indissoluble, but the sacrament makes it even more so, because whether or not they make use of it, the man and woman receive the grace to be bound with the love that binds Christ with the Church. Among the baptized, every valid marriage is a sacramental marriage. Now back to those teenagers. A few minutes of passion in the back seat do not make them married. By your description -- “we will love each other forever” – what they probably think they are promising is that they will always have amorous feelings. Not only is that far short of the marital promise – for there is nothing here about joining in a complete partnership of life in the hope of children – but in fact, it isn’t a promise at all. Why isn’t it a promise at all? Because no one can promise the impossible. Promising to have the same feelings forever is like promising to live forever. When the man and woman promise to love each other in the wedding vow, they aren’t promising to have the same feelings forever, but to persist in the commitment of their wills, each to the true good of the other. Feelings waver. Love endures.

|

A Stitch in TimeSaturday, 03-05-2016

The other day I was speaking with a student active in campus pro-life activism. I knew, of course, that often such groups need legal assistance because of attempts by opponents – including university administrations -- to shut down or hinder their activities. What I hadn’t realized was that such interference has become so common that groups like hers have found it necessary to invite attorneys to speak to them periodically about their speech and association rights, just so that they will be prepared when problems arise. A stitch in time. Speaking of administrative harassment, you do know, don’t you, that at a number of colleges and universities, administrators threaten Christian student groups with loss of accreditation unless they eliminate the requirement that their officers hold the Christian faith? One musn’t discriminate, you see.

|

SuspicionFriday, 03-04-2016

The real appeal of Bernie Sanders to the young is free tuition. The real appeal of free tuition is not charity, or even the reduction of the debt burden, but the prospect of utter and complete financial independence from parents without having to work for it. The next proposal will be a free living stipend. Why should we assume that capitalists are materialistic – but socialists aren’t?

|

To Learn How the Truth of Things StandsThursday, 03-03-2016

You would think the scholars who study the canon of Western literature would agree about what the Great Books say, but disagree about how great they really are. Well, there is a good deal of debate about how great they are, but even more about what they say -- though this is more true of some books than of others. Take Plato’s dialogue, Republic, which includes a famous analogy between the city and the soul. Some call it the first true work of political philosophy. Others say the book is only about the soul, and the political parts are just metaphor. Among those who do think it is about politics, some say Plato really believed all the outlandish things he put in Socrates’ mouth -- that philosophers should be kings but spout noble nonsense, that the ruling class must share everything in common including wives and children, and that men and women must lead the same way of life. Others have treated the work more nearly as a satire -- as though he had said “Here is how you would have to live to have peace, but of course it would be ridiculous.” And then there are those who see the book as navel-gazing, holding that its real concern isn’t politics or the soul but the tension between philosophers and the city. Or that its true concern is education. Or that the true topic of the dialogue is dialogue itself. There are devastating objections to all these views. The puzzle is so vexing that I sometimes assign grad students who are reading Republic for the first time simply to work out what question they think the dialogue is chiefly trying to answer. Initially, most assume that the question is “What is justice?” But as soon as discussion begins, their consensus collapses. The first thing they notice is that almost immediately, the participants in Plato’s dialogue are sidetracked into asking why anyone should even care about being just, considering that it seems contrary to selfish interest. Plainly, “Why should I be just?” is not the same question as “What is justice?” But wait – but wait – but wait – By the time they finish they have a dozen theories of the real question of the dialogue. And that, of course, shapes their understanding of everything else about it, including whether the question has been answered. I enjoy such mysteries, but only up to a point. As my favorite saint wrote about another riddle of authorial intent, “The purpose of the study of philosophy is not to learn what others have thought, but to learn how the truth of things stands.” How easy that is to forget. Plato agreed.

|

Suspending Moral JudgmentMonday, 02-29-2016

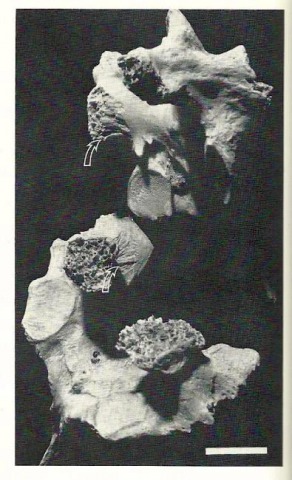

A reader comments:You’ve been blogging about faculty attitudes toward morality and religion. Let me share an incident from my introduction to anthropology course some years ago. It was a graduate “core” course, but some undergrads took it too; the grads had more work, more reading, and weekly tutorials. Before and during class one day there was talk about new discoveries about cannibalism. While forensic anthropology was not my thing, my best recollection is that the issue of cannibalism among the Indians of the Southwestern US had just been decisively proven by a forensic anthropologist from Berkeley named Tim White. White's analysis of human bones from an Anasazi pueblo in southwestern Colorado, site 5MTUMR-2346, reveals that nearly thirty men, women, and children were butchered and cooked there around A.D. 1100. While the professor and some of the students were kicking this around, four female undergrad students became restless and visibly sick at their stomachs. Several expressed verbal outrage (“That's horrible!”). The professor was visibly perturbed and spoke directly to the outraged students. She seemed outraged by their outrage, as well as gravely disappointed. “If you're going to be anthropologists,” she said, “you're going to have to learn to see things from the people's point of view. You can't be getting upset at them.” This did not sit well with everyone. The professor began the next class by announcing she had been called by the president of the university the previous night. He himself had been called by the fathers of some of the students. Their families had been caught up in the holocaust, and they did not appreciate the professor invalidating the moral values of their daughters; there is indeed right and wrong. She went on to explain to the class that she was not saying we do not make judgments, but the anthropological gaze is about describing culture, not judging it. Reply:Your professor’s surprise and dismay about her students’ healthy response to cannibalism is interesting and revealing. A colleague once commented to me about what happened when he assigned his freshman class to read the bioethicist Peter Singer’s defense of infanticide. Those students too were upset (which heartens me) – but he was puzzled that they were. In his view, their response was intellectually immature. It was as though he thought the task of moral philosophy was not to uplift and improve our moral judgments, but to desensitize us to moral distinctions. Something of the same notion comes across in your professor’s statement “The anthropological gaze is about describing culture, not judging it.” Do you notice her tacit assumption? She didn’t consider moral facts to be real facts, for if they were, then the description of culture would include evaluating it. You don’t thicken description by throwing out facts, but by getting them all in. The ancient historians and students of society took the opposite view. Aristotle, for example, thought that in classifying the different kinds of political societies, the moral motives of the ruling class are just as important as their social composition. In other words, if in one state the ruler promote the common good but in another they promote their personal interests, these are different kinds of government, and if you don’t see that, then you are hardly seeing at all. He distinguished six basic kinds of regime – kingship, aristocracy, polity, tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy – in one column the good ones, in the other, perversions of the good ones. Our approach would distinguish only three. My point isn’t that we shouldn’t suspend moral judgment; I don’t think that we can. Whenever we imagine that we are suspending moral judgment, we are deluding ourselves. What is actually happening is that certain moral judgments which are recognized as moral judgments are being pushed out the front door – but certain others which are not admitted to be moral judgments are slipping in the back door. We don’t judge cannibals; we do judge those awful judgmentalists.

|

Majoring in Natural LawSunday, 02-28-2016

Question:I'm curious whether you know of any undergraduate degrees that are exclusive to the study of natural law. If there are none that you know of, do you know of any program that has natural law as its main emphasis? Reply:No, I don’t think there are any such programs, but don’t be discouraged; there shouldn’t be. The best way to prepare for the study of natural law is to get a broad, classical liberal arts education which is heavy in ethical and political philosophy. Of course you will want teachers who are well-informed about the classical natural law tradition and sympathetic to it. It would be wonderful if they taught other subjects, such as history and psychology, from the perspective of natural law. You should supplement your classroom studies with independent reading about natural law, and if you tell me what you’ve read already, I can suggest other things to read. But I don’t think it would be good to try to turn natural law into the whole content of your major, even if there were such a program.

|