The Underground Thomist

Blog

“You Must Write a Thriller!”Saturday, 02-13-2016

Not long ago in this blog, I reported the views of Eduard Habsburg-Lothringen, the new Hungarian ambassador to the Court of St. Peter, concerning why Thomistic philosophy disappeared (thankfully, only for a while) during the third quarter of the twentieth century. Afterward the Ambassador graciously emailed to comment on my post. Combining portions of several notes back and forth, I quote here with his permission.

Dear Underground Thomist:Thanks for your feedback on your blog about my theories on the fall of Thomism. Unfortunately, my thesis has not been translated into English, you (as a Thomist) would doubtlessly find it a fun read. I wrote a more detailed account in Osservatore Romano a little while ago, but that’s in Italian. The scan is longer than the online text, which has been shortened by about one-quarter. The article recounts the story of when Cardinal Ratzinger, whom I interviewed for my thesis 25 years ago, met me later and encouraged me to write either “a TV documentary or a thriller” on the fall of Thomism. Anyway, I tweeted your blog post. You don’t seem to be on Twitter? Greeting from the Urbs Eduard Habsburg Ambasciatore Ambasciata di Ungheria presso la Santa Sede

Dear Ambassador Habsburg:Thank you for your reply to my post. I’m glad you liked it, and am sure I would enjoy your dissertation. No, I’m not on Twitter – on social media, I am such a dinosaur that instead of tweeting I would have to grunt. Then again, if dinosaurs really were ancestors of birds, perhaps they did tweet. Thanks, too, for permission to quote from your notes. Below, I have very roughly paraphrased a section from the Osservatore Romano article, which I am sure will interest my readers. By the way, your tweet says, “Underground Thomist agrees/disagrees with my analysis of the Fall of Thomism.” Actually I agreed entirely with your analysis; I was merely reflecting upon what seemed to me the foolishness of the attitude of the theologians who thought St. Thomas irrelevant to the study of the Fathers. Greetings to the Urbs, from the Suburbs J. Budziszewski Professor of Government and Philosophy University of Texas at Austin

“You Must Write a Thriller!”(excerpted and roughly paraphrased from the original Italian) Between the Second Vatican Council [1962-1965] and 1968, Thomism disappeared completely – no noise, no fuss. It disappeared, but I wanted to know whether its disappearance was due to murder, illness or accident. So I jumped in the car – this was in 1993 -- and visited the great legends of Thomism in Europe: Joseph Pieper and Marie-Dominique Philippe, Hyacinthe Paissac and Józef Maria Bocheński, Joseph de Finance and, though unfortunately, only for a few minutes, Yves Congar. I spoke with some twenty teachers, filling my tape recorder with interviews lasting up to two hours. The two most touching moments were probably, [first,] the conversation with Christoph Schönborn, today Cardinal Schönborn, who told me [how at the Domincan Saulchoir, the teaching of] Thomism was forbidden, [so that] Schönborn learned it in secret, from an old Dominican, with a small group that met in a dorm. Then, the meeting with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith .... The prefect spoke to me mostly of his impressions of the disappearance of Thomism during the Council itself. But much later, when I sent him the conclusion of my argument, he wrote me a nice letter saying that it would be very important for me to continue the story, describing the subsequent events. He suggested "a documentary for television -- or a thriller!”

|

Teaching ChildrenFriday, 02-12-2016

Related:What We Teach When We Don’t TeachHow You Are Different from a TurnipA surprising number of parents tell me that they are afraid to “force” their children to worship with them, because then the kids might come to resent religion. By this reasoning, children should not be “forced” to take baths for fear that they will come to despise cleanliness, “forced” to be gentle with smaller children for fear that they will come to hate kindness, “forced” to do their homework for fear that they will come to love stupidity, or “forced” to share family meals for fear that they will come to loathe the taste of food. Faith is not the same thing as compliance, but compliance and imitation are how children learn everything. Children do not naturally resent God or the worship of God. What we find in the nature we share with Him is not an aversion but a longing: As one of the Wisdom books says, He has “put eternity in their hearts.” But to listen to that eternity they must be taught how to do so. They must see us loving God. I am flooded with gratitude that my parents and grandparents taught me well enough that after abandoning Him I knew how to return; vanquished when I reflect that when my wife and I did return, and began to worship regularly, our children, small then, were delighted. Concerning the teachings of the faith, a certain late Bronze Age people were taught, “"You shall therefore lay up these words of mine in your heart and in your soul; and you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. And you shall teach them to your children, talking of them when you are sitting in your house, and when you are walking by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. And you shall write them upon the doorposts of your house and upon your gates, that your days and the days of your children may be multiplied in the land.”

|

Pay Me Before I Rob AgainThursday, 02-11-2016

Accoring to a recent AP story, the District of Columbia is planning to pay released felons who agree to behavioral therapy up to $9,000 a year not to commit crimes. Good idea. We could solve all our social problems this way. Schoolyard bullies could be paid not to beat up smaller children. Fast food workers could be paid not to sneeze on customers. High school boys could be paid not to impregnate high school girls. College students could be paid not to cut classes -- better yet, faculty could be. Sociopaths could be paid not to run for public office. Iran and North Korea could be paid not to make nuclear weapons. I mean Iran and North Korea could be paid again not to make nuclear weapons. History is so interesting.

|

Wagon TrainWednesday, 02-10-2016

Question:You’ve addressed prejudice in graduate admissions against serious Christians in two posts (by the way, your line “Cry reason and let slip the dogs of argument” is by far my new favorite quotation). Fortunately, the people who wrote my own grad school recommendations were well aware of the problem. But what, if anything, can be done to address the problem of hostile admissions committees? P.S. I know you are a Renaissance man, but if you tell me you can speak Klingon, I will be truly amazed. Please ease my curiosity on this matter. Reply:In the short run, almost nothing can be done; you can’t expect admissions committees to be reasonable when the universities themselves are unreasonable. But if you take the long view, a lot can be done. The real task is to build a new intellectual culture. Undergrads should prepare not just by doing their coursework but by reading widely outside of it. Excellent suggestions about what to read can be found in the Student Guides to the Major Disciplines, available through the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. Though you can purchase them, I believe PDF versions are available for free. Christian students should also read widely in the classics of faith. It’s amazing how much is available online – works of the Patristic writers such as St. Augustine’s Confessions and City of God, works of Thomas Aquinas such as the Summa Theologiae and Summa Contra Gentiles, and all sorts of other things like G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man and C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, The Abolition of Man, and The Screwtape Letters. Then get your foot in the door. That’s why the second post warned grad school recommenders not to frighten the timid and easily-alarmed secularists on admissions committees by praising applicants for being persons of faith. Once you get through the door, excel. That’s what I meant in the first post when I wrote “Cry reason and let slip the dogs of argument.” To be viewed as half as good, grad students who reject the secularist and relativist consensus will have to be twice as good – and I mean twice as good at using their minds. Which is not a bad training. Both during your graduate training and after you get your degree, think big. The problem is that our intellectual culture is grounded on practical atheism; you don’t have to be an atheist, but you are expected to impersonate one. Your calling is to work out the alternative. Because you can’t even begin to work it out alone, join with other people are trying to do the same thing. I’ve written about that lately too, here and here. Think through the implications of Christian faith for scholarship. Form intellectual wagon trains. Be pioneers. The very fact that you reject the prevailing academic ideology will offend many people. Don’t shrink from tough critique, but distinguish between avoidable and unavoidable offense. Be winsome. Persuade. Now as to your postscript. I am sorry to disappoint you, but I am not a Renaissance man, and I don’t know a word of Klingon. But I can tell you this: vIq Hol Qatlh. mughmeH Qatlh. *

|

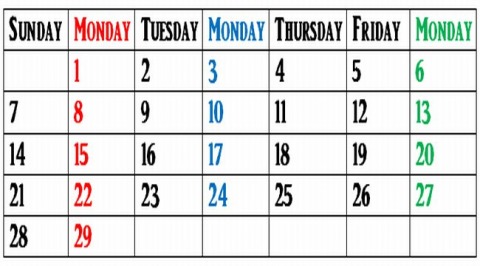

A Richer Blend of MondaysTuesday, 02-09-2016

The most popular day on this blog is Monday, when I reply to letters I’ve received. What do you think? Should I run letters posts more often? I wouldn’t fill the week with Mondays, but a richer blend of Mondays might be interesting. Let’s try it. If you are so inclined, write. We’ll see how it goes.

|

The Consequences of ConsequentialismMonday, 02-08-2016

As my regular readers know, I reserve Mondays for letters. This one is from an undergrad student.Question:The other day someone told me a scenario from the war in Bosnia in the 1990s. As a matter of military policy, Serbian units systematically raped Bosnian women. One soldier refused to participate. As a punishment, his commander took the inhabitants of an internment camp, divided them in two, and ordered the soldier to kill half. If the soldier refused, the officer would kill them all, and kill him too. As St. Paul said, it is wrong to do evil so that good will result. So I said the soldier should refuse to rape or murder no matter what the consequences. The other guy was not convinced. He thought the soldier should have given in because the results would have been better: In the end, fewer people would have died. How would you have answered him? Reply:The other guy's view is called “consequentialism.” Consequentialism means that when you're deciding what to do, nothing matters but results. Be sure you get the point: Consequentialists don't just say results matter; we all believe that. They argue that nothing else matters but results -- that results can turn intrinsic evil into good. Is it all right to lie and cheat? Is it all right to have an abortion? Is it all right to sleep with your girlfriend? Is it all right to commit atrocities? The consequentialist’s answer will always be the same: “It depends.” What does it depend on? The results. Can results really make intrinsic wrong right? The question comes up every day, and it isn't just for armchair philosophers. Consequentialism wrecks lives. Also civilizations. It has gone a long way toward wrecking ours. It's difficult to get through to someone who takes the results-only line, but keep trying. One way is to make your friend begin doubting his assumptions about what the results will be. Another is to show him that ironically, the attitude “nothing matters but results” has bad results. Best of all and most fundamental is get his conscience on your side -- to show him that something does matter besides results. In your shoes, I might make one of the following points. Don’t drop them all on your friend. A conversation isn’t a bombing run. 1. “Considering that genocide was Serbian policy, it would have been naïve to think that a promise like 'If you murder these, then I won't murder those' can be taken seriously. The only real question facing the soldier was whether he would join in the murdering.” 2. “The Serbians committed genocide for the sake of consequences that they considered better. If the soldier agreed to participate in their murders for the sake of consequences that he considered better, then how would his hands be less dirty than theirs?” 3. “Participating in murder for fear of consequences has a consequence too. The consequence is that you yourself become a murderer. Can you live with that?” 4. “Sometimes those who commit atrocities are even more intent in getting others to cooperate with their atrocities. So if you do become complicit, you’re not just helping them kill. Aren’t you also helping them turn people like you into people like them? And don’t you then acquire a motive not to bring them to justice, because you too would be punished?” 5. “According to consequentialism, nothing whatsoever is intrinsically wrong -- not even systematic rape and genocide. Anything whatsoever is okay if the consequences are good enough. Look me in the eye. Is that what you really believe?” 6. “Suppose we all did become consequentialists. We would then live in a world in which people did believe that nothing whatsoever is intrinsically wrong, in which they did believe that anything whatsoever is okay if it gets the results that we want. What would be the results – the consequences -- if everyone did take that line?” 7. “Is there anything you wouldn't do for the sake of results you liked better? Would you murder six million Jews, like Hitler? Would you molest children? Would you eat them? Would you rape and torture your mother? What -- did I hear you say “No”? Did I hear you say that there is at least one thing you wouldn't do no matter what? Then you admit consequentialism is wrong.” Start with the last point. Most people are consequentialists only when their consciences don't hurt enough yet.

|

How the Meaning of Liberty Did and Didn’t ChangeSunday, 02-07-2016

Aristotle famously remarks that everything which the law does not expressly permit is forbidden. Some people take this as showing how different the classical concept of liberty is from the modern one. For we say just the opposite: That everything which the law does not expressly forbid is permitted. There really is a difference between the classical and modern concepts of liberty, but that isn’t it. If Aristotle’s remark had been intended literally, it would be absurd. Because of the law’s silence about rotation, respiration, and osculation, you would be forbidden to turn over in bed, take a breath, or kiss your spouse. What Aristotle did mean by his comment isn’t clear, but there are all sorts of ways to make sense of it without taking it literally. What he actually says is that “the law does not expressly permit suicide, and what it does not expressly permit it forbids.” But suicide is self-murder, and murder is expressly forbidden by the law. So some think he might mean only that in the context of an existing prohibition, any act for which the law does not expressly declare an exception is prohibited. So if that isn’t it, then what is the difference between the classical and modern concepts of liberty? Among the classical thinkers (bearing in mind that not all ancient thinkers were classical), the term “liberty” referred not to the absence of governance, but to a certain kind of governance -- whether over a multitude of people, a single man, or an aspect of a man. Thus, in the political sense, the people of a republic were called “free” because they collectively ruled themselves (rather than being under the thumb of a tyrant). In the domestic sense, a freeman was called “free” because he ruled himself (rather than being ruled by a master). In the moral sense, a virtuous man was called “free” because he was ruled by the principle which most fully expressed his nature, his reason (rather than being at the mercy of his desires). And in the religious sense, a Christian was called “free” because he served the Author of his being, in whose image he was made, apart from whom he could not truly be himself, for to be alienated from the one in whose image I am made is to be alienated from my own being. By degrees, the meaning of the term changed. So long as they do not think too deeply about the matter, modern people tend to regard freedom not as freedom from the wrong kind of rule, but as freedom from rule. In the political sense, this would make the people of a republic freer than the people of a tyranny only if they happened to make fewer rules for themselves than a tyrant would. In fact, the only true freedom would be anarchy, which has no rules at all, although freedom in this sense turns out to be inconvenient. In the domestic sense, a freeman would be freer than a slave not because he ruled himself, but only because he was more nearly able to do as he pleased – if, in fact, he was more nearly able. In the moral sense, a virtuous man would be freer than a vicious one only if his reason happened to put less constraint on his will than his base desires did. The only true freedom would be following whatever impulse one happened to have at the moment. However one might dress this up by calling it “autonomy,” as though we were gods, the condition is less superhuman than subhuman. In the religious sense, a person would be free only if he served nothing and no one. Since in this view of things, God looks like a tyrant, some suppose that the only free spirit is the atheist. Carrying the modern line of reasoning still further, some take the view that not even the atheist is truly free, if he serves the cause of atheism. The culmination of the modern idea is that no one is truly free unless he does what he does merely because he does it; unless he has no particular reason for doing anything at all; unless his choices are meaningless. In this sense, freedom is not so much inconvenient as futile, and human existence is absurd. Which is just what such people conclude.

|