The Underground Thomist

Blog

Waiting to FallSaturday, 04-16-2016

The paradox of the sexual revolution is that those who preach it belong mostly to the upper stratum, but those who suffer from it belong mostly to the lower. Will this difference persist? I don't think it can. Although, as I conceded in a previous post, wealth can compensate for a while for the natural consequences of sexual irregularity, the cost of compensation becomes greater and greater. Well-off parents of the last generation who no longer believed in the old sexual norms and kept up their marriages merely as a social pretense provided at least a shred of stability to their children. But the children of these parents no longer believe even in the pretense, and the chances they take make their parents look like pikers. Their own children will be worse off than they are.

|

These Chocolates but Not ThoseFriday, 04-15-2016

People sometimes tell me that they believe there may be some natural laws – okay, it’s wrong to murder -- but that there are no natural laws about sexuality. They simply refuse to consider that sex might be ordered to procreation. During a recent conversation, when I drew attention to the natural consequences of loose sex, such as fatherless children, one person said, “You make that so black and white!” Another said, “That’s just a religious opinion. Shouldn’t it be up to the individual?” Another asked “Isn’t there a mean between extremes?” I suppose the first protestor meant that not every natural consequence always happens – just as a person may walk into moving traffic and yet not be hit by a car. Yes, but does that make it smart to walk into moving traffic? As to the second protestor, if it is a religious opinion to suggest that individual choice doesn't trump everything, then it is also a religious opinion to suggest that it does. The god of the former religion is the author of human nature. The god of the latter is “Me.” The third protestor was onto something. Yes, of course there is a mean. Locating it is exactly what we are trying to do. Between the extreme of careless sex and the extreme of revulsion from sex, we find it by considering the good of the children and the good of the union of their parents. It turns out to be marriage. I am such a meanie.

|

News from the FrontThursday, 04-14-2016

Has the population of the hookup world suddenly become more numerous than before the HHS mandate and before Obergefell? No, but its inhabitants are more openly angry about rational criticism, and the minority are less willing to speak up.

|

Social JusticeTuesday, 04-12-2016

It is a trifle for the upper strata to promote sexual liberation; those who have money can shield themselves (to degree, and for a while) from at least some of the consequences of loose sexuality. The working classes do not have that luxury. In a country like this one, serial cohabitation and childbearing outside of marriage contribute more to poverty, dependency, and inequality than a million greedy capitalists do. Do you to really want to raise up the poor? Then do as the English Methodists did in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: First live the Commandments. Then go among the people and preach them. Start with the ones about marriage and family. I do not say this is all you should do, but if you won’t even do so much as this, then the rest of your social justice talk is hypocritical. You may as well admit that it is all about you.

|

Diving InMonday, 04-11-2016

Question:I have been inclined to read your commentary on Thomas Aquinas’s Treatise on Law for some time, but I have been stumped by a prior question. I am worried that I cannot understand St. Thomas on law without a better understanding of his thought on politics. The two go hand in hand, right? But I know that his commentary on Aristotle’s Politics is really not complete, and what else we have from him (On Kingship, for example) is not extensive either. So, I guess my question is this: what would you recommend as the proper preparation for assimilating the teaching of the Treatise? Aristotle's Politics? Plato? Leo Strauss? Alasdair MacIntyre? Or maybe I have it wrong, and your commentary is sort of sui generis? Maybe it is a mistake for me to try to situate the ideas fully in a political teaching and so I should just dive in? Any help on this would be greatly appreciated. Reply:I think it’s fine to begin with St. Thomas, but by all means read the other classical writers too. Read as much as you can! Feast on all those riches! Most people find it better to read the ancient and medieval writers before the moderns, not just because they came first, but also because the moderns forgot so much of what the previous writers wrote and became confused about the rest. But there is no one way to do this. The important thing is to jump in and start swimming. Since you’re drawn to the Angelic Doctor and his views on law, I don’t see any reason why you shouldn’t dive right into the Treatise. True, you should read the Treatise in the context of St. Thomas’s other work, but that doesn’t mean you have to read all the other works you mention first. In fact, I would suggest saving them until later. His work on kingship is a quirky special-purpose work. His commentaries on Aristotle are intended to explain Aristotle’s thought, rather than his own. Yes, secondary sources can be helpful, but even so, I think you should always begin with the author’s own words -- otherwise your baloney meter won’t be calibrated well enough to detect whether the secondary source is helping you or feeding you baloney. Of course, my own commentary on the Treatise is a secondary source too, so don’t throw away caution! But in a line-by-line commentary, where you have all of the author’s original words, you can tell more easily whether the commentator is playing tricks with them. That’s one of the reasons I’m trying to bring this genre of writing back. Still, if my book doesn’t help you, drop it like a hot potato. You can always come back to it later. The same goes for the work of any scholar.

|

Forked TongueSunday, 04-10-2016

How often we hear people argue that we ought to promote animal rights, because, since we can’t read animal minds, they might, for all we know, be persons. Yet often people of the same persuasion argue that we ought to allow abortions, because, since we can’t read baby minds, we have no reason to think they are persons.

|

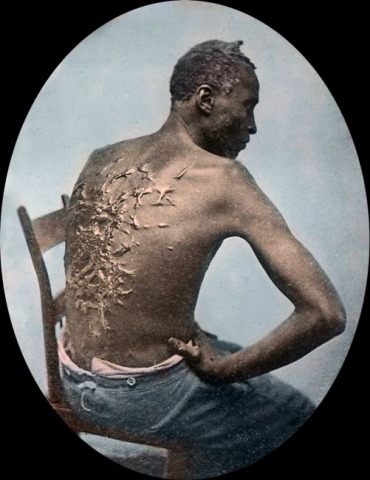

Gods of the LashSaturday, 04-09-2016

And I should imagine that this is equally true of the soul, Callicles; when a man is stripped of the body, all the natural or acquired affections of the soul are laid open to view. -- Socrates Those who reject God don’t reject gods in general. Each of them makes something else his god. Some, of course, make gods of cruel causes such as fascism, communism, and Islamic terrorism, but it seems that far more pursue the gods of pleasure, wealth, power, sex, or being thought well of by others. Could it be that people in that larger category are seeking gods that don’t ask anything of them? Maybe that is what they think they are doing. But every god but the true God is a slavedriver and taskmaster, a god of the lash. Consider just the god of the hedonists. Think of all you must sacrifice to give pleasure your unconditional loyalty. Think of all the things you must give up. Think of all the longings you must uproot. Think of all the nerves you must kill.

|