The Underground Thomist

Blog

Parts and Wholes (Part 1 of 2)Tuesday, 11-25-2014Every person’s life is bound up with his membership in the community. I am more than just a solitary atom; I am a part of a whole. But the individual's identity is not exhausted by his membership in the community. As Thomas Aquinas explains, the kind of unity that the commonwealth enjoys is not a "unity of essence" or a "unity of matter," but only a "unity of order," amounting to no more than the fact that things stand in a shared relationship. "To be one in respect of order is not to be one unqualifiedly speaking," he says, "since unity of order is the least of unities." Consequently, although I am a part of the community, I am not only a part. A person is not like a hand, which takes its entire identity from the body to which it belongs. He is a complete being, subsisting of himself, distinct from all else, the ultimate possessor of his properties in the sense that they are predicated of him, not of anything or anyone else. Even so, his membership in the community matters. It is not just something that affects him, but something about him. The fact that I am a part does not imply that I am only a part; but neither does the fact that I am not only a part imply that I am not a part.

|

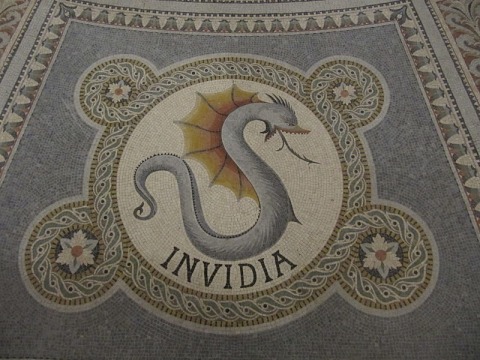

EnvySunday, 11-23-2014

Not all common goods are equally common. In the weak sense, a good is common merely when it is good for everyone, like pure water. Different people in the community may enjoy different amounts of weakly common goods. In fact, if one person grabs more of a weakly common good, then other people have less. For example, I might divert part of the river away from your property and onto mine. In the strong sense, a good is common when one person's gain is not another's loss, so that our interests literally cannot diverge. The best examples of strongly common goods are the virtues, the goods of character: I don’t become less wise, or less just, or less courageous, just because my neighbor becomes more so. Yet there is a paradox, for although we can’t really be in competition for strongly common goods, we may feel as though we are. Suppose I envy you for being wiser than I am. This is plainly irrational, because the greatness of your wisdom doesn’t leave less wisdom for me; I might even gain wisdom from your teaching and example. But the envious man does not see it that way. Even though the greatness of your wisdom does not diminish the absolute amount of my wisdom, it does diminish the relative amount of my wisdom, for the wiser you are, the lower I rank in comparison, especially in the eyes of others. I may therefore sorrow that we cannot trade places; I might wish that you were less wise, and I were more. Although we cannot really be in competition for wisdom, we can certainly be in competition for rank, and so, unexpectedly, something that in one sense excludes the very possibility of rivalry in another sense becomes a motive for rivalry.

|

Grammar SchoolSunday, 11-23-2014Perhaps this will amuse no one but me, but I am surprised by how many reviewers are unable to bring themselves to use the correct title of my book What We Can’t Not Know. They cite it as What We Cannot Not Know. What explains this funny scruple? My guess is that they are haunted by the spirits of long-dead schoolteachers who drilled into them that contractions have no place in genteel prose. That’s prob’ly what happened.

|

The Hamburger Helper of Regime Design (Part 2 of 2)Saturday, 11-22-2014

Yesterday I suggested that James Madison’s Constitutional strategy of “pitting ambition against ambition” is like Hamburger Helper. Just as meat extenders don’t substitute for meat, so his strategy doesn’t substitute for virtue: It merely helps the little bit we have go a little bit further. The theory works like this: A man who is driven by ambition has a strong motive to restrain other ambitious men, because the more power they attain, the less is left over for him. If he has no virtue at all, he may restrain them by playing dirty. If if he has just a little virtue, perhaps he will content himself with clean weapons like constitutional checks and balances. So everyone is restrained by everyone else, and we are all better off. The underlying theory can be generalized: Provided that there is some residuum of virtue, sub-virtuous motives can be channeled to keep even greater vices in check, thereby extending virtue’s work. Here are a few other example: For capitalism, the sub-virtuous motive is desire for wealth. If businessmen have no virtue at all, they will seek wealth by defrauding their customers and seeking to obtain monopolies from the government. But if only they have just a little virtue, they might compete within a framework of laws against fraud and monopoly by lowering the price and improving the product, to the benefit of all. For the Roman Republic, the sub-virtuous motive was desire for glory. If the nobility has no virtue, they will seek glory by corrupting the electorate and assassinating their rivals. But if only they have just a little virtue, they might compete within a framework of shared expectations about what is and isn’t done by performing acts of conspicuous benefit to the commonwealth. The flaw in the strategy of using vices to counteract even greater vices was recognized by St. Augustine in his great fifth century work City of God Against the Pagans. Remember, without that little bit of virtue to steer them, men will pursue their sub-virtuous interests in the wrong ways rather than the right ones. But the more one relies on such interests, the more the reservoir of virtue is drained. So unless something replenishes this reservoir, the strategy collapses. (What can replenish it? Now there is a question for political theorists!) Augustine thinks this is why the republican love of glory was replaced by the sheer lust for wealth and power, and the republic collapsed. He who trains dragons to keep wolves under control must reward them with food. Eventually the dragons grow large enough to hunt their own food. At this point they set aside their training and do as they please.

|

The Hamburger Helper of Regime Design (Part 1 of 2)Friday, 11-21-2014

The idea of the common good is fading, and we are the poorer for it. I have met students of law and government who have never even heard the expression “common good.” One approached me after a lecture in which I had used the phrase, explaining that she had no idea what I meant. In the course of conversation, she told me that every one of her previous professors had taught her that law and politics are nothing but the expression of private interests. A charitable interpretation is that the young woman’s previous professors had been trying to explain the point that the Constitutional framer James Madison was making when he famously wrote that “the regulation of ... various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation, and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of the government.” As he went on to point out, “It is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good . Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” Therefore he called for “a policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives,” saying that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” But on closer examination, not even Madison believed in universal selfishness as the basis of law. Though he considered it naive to assume that virtuous statesmen would always be at the helm, he thought it would be dreadfully irresponsible not to try to put them there. Thus he wrote, “The aim of every political constitution is, or ought to be, first to obtain for rulers men who possess most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue, the common good of the society; and in the next place, to take the most effectual precautions for keeping them virtuous whilst they continue to hold their public trust.” Actually, then, our founders viewed the strategy of pitting ambition against ambition merely as a way to “stretch” virtue, to make what little we have go a bit further, to get more bang for the buck. It doesn’t work without any virtue at all, any more than gasoline additives work without gas, or Hamburger Helper works without hamburger.

|

Tread the RazorThursday, 11-20-2014In your relations with those in whom there is something to disapprove, tread the razor. I am speaking of things I do not fully understand. But someone who understood them better, I think, might speak to us as follows. In fear you must avoid both connivance at my bad moral character, and the greater monstrosity of moral pride. If you avoid me because of what I do, do it because you are not good enough to be with a man as bad as me, not because you are too good. If you say in your heart that you are too good, it were better that you sought my company. If you say in your heart that you are better than me, it were better that you did connive at my wrong. For that secret will make you the worse of us, unless I play at the same game. You may avoid my society, but you must not flaunt the avoidance. Though it may be your duty to warn others against me, it cannot be your right to do so out of malice. Though you know that your aloofness may cause pain, the production of pain must not be your aim. You may deny me discretionary benefits if it is your office to make the decision, but you may not deny those benefits that are my due as a human being, especially those which might assist the amendment of my life. Though you withdraw approval from my flaws, you may not withhold charity from my person. Refuse to indulge in yourself the conceit that you can examine my soul; remember your own proneness to vice and error; and at all times remember that you are an object of tolerance to others – especially when you are most inclined to pass judgment on me.

|

Rules and VirtuesWednesday, 11-19-2014

A chasm is sometimes proposed between so-called virtue ethics and so-called rule or law ethics. Unless we are thinking of bad theories of ethics, there is no such chasm. In the first place, every complete theory of moral law requires a theory of virtue. If I do not have the proper dispositions, the right habits of mind and heart, then how will I recognize true moral rules and distinguish them from false? For that matter, how will I even be able to apply the rules I know already? It is one thing to know that I must not steal; it is quite another to see that this would be stealing. For that I need virtue. But every complete theory of virtue also requires a theory of moral law. Even Aristotle, supposed by some to be the paradigm case of a moral philosopher who talked only about virtue and not about law, talks about law. He holds that the man of practical wisdom acts according to a rational principle; this principle functions as law. He holds that virtue lies in a mean, but that there is no mean of things like adultery; this implies that there are exceptionless precepts, which also function as law. He holds that besides the enactments of governments and the customs of peoples there is an unwritten norm to which governments and peoples defer; this norm too is a law. The awareness of law creeps in through the back door even when it is pushed out the front -- and Aristotle wasn’t even pushing.

|